|

Detail views of the coloured claddings and pivoting ceremonial entrance panel of the forcourt pavilion. Detail views of the coloured claddings and pivoting ceremonial entrance panel of the forcourt pavilion.

Looking along the forecourt’s reflection pond at dusk.

Interior of the High Court at the top of the building, illuminated by uplights within veneered columns.

Internal entrance to a typical courtroom.

Concept sketch of the interior by Paul Katsieris.

left Interior looking north with public concourses at left, offices to the right and a view of Flagstaff Gardens ahead. right Bridges link concourses to courtooms; the boxes of coloured panels are interview and witness rooms.

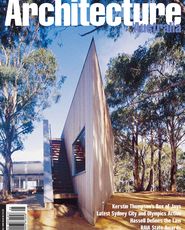

The entry pavilion and main curtain walls showing intricate patterns arising from strategies of dilation, expansion, alignment and misalignment.

North facades, designed as complex high-tech tapestries.

Images: John Gollings

|

|

Project Description

A new Commonwealth Law Courts complex has been built in Melbourne to a Hassell design which consolidates the High Court, the Federal Court and the Family Court into a 17-storey block opposite Flagstaff Gardens. The building is conceived as two blocks— one for courts and one for offices and public areas—divided by a north-south gallery/lightwell and linked by footbridges. The main William Street arrival has a ceremonial forecourt with a reflection pond and entrance pavilion. The building’s lower levels house courtrooms and hearing and meeting rooms; upper levels contain chambers, with the top floor housing the High Court.

Architect’s Statement by Paul Katsieris

With the possible exception of churches, cathedrals, temples, few building types other than law courts can better embody pure architecture. The institution is expected to uphold the law, to demonstrate a certain purity, to manifest a symbolic weight or an anchorage in an increasingly virtual and dissolving public realm. Purity in this charged context is seen as a necessary precondition justifying the power vested in, and yielded by, the institution. In this project, an attempt is made to work with mass, weight, gravity and the almost disappeared paradigm of entasis. We have attempted to understand entasis as a condition less to do with optical refinement and more to do with the manipulation of static wall forms such that they appear to exhibit tension. Straining. Movement about to be. A curtain wall poised between static and plastic aesthetic states.

Comment by Hamish Lyon

What should a public building look like? In what style should it be designed? Although these might sound like banal questions, they are central to the current architectural debate in Melbourne. Given the prevailing ideology of the Kennett government towards the privitisation of public assets, there has been a subsequent side effect that blurs the traditional definition of public architecture. Major infrastructure in Victoria is now built, owned and operated through private sector financing, with the government as nothing more than an end user. This condition is reflected in a cultural uncertainty between the institution as the symbol of a collective idealism or as simply the anonymous outcome of market economics. It appears that monumentality and virtue have been replaced by consumerism and consumption.

The new Commonwealth Law Courts, by Hassell Architects, explores these circumstances through both the symbolic context of a major public institution in Australia and as a significant urban building within the 19th century grid of Melbourne. As a representation of the upper tiers of Federal justice, the new court complex has re-entered the debate on appropriate styling of court architecture, which was last stimulated 25 years ago with Colin Madigan’s design for the High Court in Canberra. The language of the Commonwealth Law Courts is steeped in the traditions of international modernism. At first, this would seem unusual for a contemporary Australian public building. In many ways, however, this building continues the grand traditions of the 19th century, when the use of style, as in Gothic or Classical Revival, was complicit with concerns for public morality. Augustus Pugin and Sir Charles Barry’s design for the Houses of Parliament, London (begun 1836), were as much a proposition about architectural composition as a treatise on the virtuous nature of Gothic architecture. Hassell’s reincarnation of the language of high style modernism appears equally imbued with this desire for a morally redemptive architecture. The taut curtain walls of the primary facades are sophisticated essays in modernism. The tapestries of lines, grids and panels oscillate with different densities and opacities, operating only within the dimension of the glass skin. Similarly, the functional zones are clearly expressed through the formal compositions of external surfaces, to the extent that the most senior judges are afforded a symbol of their status by the attribution of an individual balcony. Images of Le Corbusier’s utopian vision for the Unité d’Habitation, or the relentless beauty of Skidmore Owings and Merrill’s corporate towers, resonate in the architecture of Hassell’s latest work like much-loved pictures in the family photo album. This project also recalls the social concerns of the modernist architect as purveyor of universal truth. The project is most compelling when considered as a piece of urban architecture. Situated on the corner of William and Latrobe Streets the site is the northern culmination of Melbourne’s legal precinct and at the threshold of one of the city’s colonial green spaces: the Flagstaff Gardens. The site was also constrained by an important practical problem: the main street corner could not withstand the structural loading of a high-rise building, because an underground rail station operates directly below. This raised an unthinkable prospect for the Melbourne City Council, because its central city policy has long required all new buildings to address the street in strict accordance with the 19th century emphasis on streetscape.

Hassell’s project designer, Paul Katsieris, resolved this contradiction in the tradition of a true architect by developing a response via a three-day workshop, complete with client. The outcome of this exercise is a skilful urban gesture which addresses the corner not through the conventional idiom of an architectural feature but through the use of a negative space. As part of this strategy, the plan for the building is an L-shape which defines an urban plaza that is both a ceremonial forecourt and a public podium for controlling a number of miscellaneous service shafts rising from the station below. The entry to the building is contained in a small pavilion at the centre of the forecourt; a structure which appears more like an information kiosk than the formal entry to a major national institution. The transparency of the entry pod is contained beneath a solid portal, clad in an abstract pattern of coloured panels that shimmer with an intensity much needed in the subdued grey context of the forecourt.

Its success is revealed by the sequential arrival into the main interior volume of the building. Rising six levels and extending an entire city block from Latrobe to Little Lonsdale Street, the grandeur of this space affirms the status of the Federal Court. A glass curtain wall at the northern end of the space provides an uninterrupted view across to the Flagstaff Gardens and allows sunlight to penetrate deep into the interior of the building. A concrete curving stair in the tradition of a 1920s ocean liner anchors one end of the atrium while, at the other, two small pavilions suggest an internal laneway. The interiors throughout the complex are characterised by a wash of natural light. Given the complexity of the functional program and the need for a myriad of small internal rooms, this is an achievement which will clearly establish a new benchmark for court design in Australia. Even courtrooms that would otherwise be locked in darkness at the centre of a dense plan are afforded external views by the use of appropriately positioned mirrors and judicious openings. It is the interior detailing and the skilful manipulation of surface textures within the main public spaces that elevates this work to the level of civility and stature necessary for the performance of its role as a major public building. The effects of this building on the debate about the relevant style for the Architecture of Justice will be a long time coming. These sorts of building appear on the horizon only by the count of decades, not years. That said, Hassell has produced a remarkable building that not only deserves respect but also demonstrates that architecture can still engender a level of idealism and optimism, despite the prevailing politics.

|

Detail views of the coloured claddings and pivoting ceremonial entrance panel of the forcourt pavilion.

Detail views of the coloured claddings and pivoting ceremonial entrance panel of the forcourt pavilion.