The Derwent River stitches Hobart’s waterfront and the Museum of New and Old Art (MONA) together. Hobart’s industrial and suburban past is revealed along the majestic length of river that separates the city from the museum – a beautiful setting that is an inspiration to locals and, now, to curators at MONA. Since its doors opened in January 2011, MONA has exceeded all expectations and, in addition to its architectural success (as discussed in these pages and many others), its impact has reached well beyond the walls of a single building. With numerous events and spin-off projects – among them, the wonderful GASP walkway – MONA has become Hobart, and custodian of its polluted river. Catching the ferry from Brooke Street Pier in Hobart to MONA, one passes boatbuilding sheds and the still operating zinc works. Though it is increasingly rare to see making occurring anywhere in Australia, let alone on the banks of such an idyllic body of water, the experience is bittersweet: the beauty of industry bound to a legacy of pollution, depositing heavy metals into the river.

The Heavy Metal Retaining Wall: resting place, servery, shelter, didactic architectural object, remedial artwork, tomb.

Image: Jonathan Wherrett

The Heavy Metal Retaining Wall was opened at the annual MONA Festival of Music and Art (playfully nicknamed MOFO). It is part of the larger River Derwent Heavy Metals Project – a series of ongoing projects, curated by Kirsha Kaechele, which brings art and science together to educate and help rid the river of its heavy metal pollutants. The wall sits on the lawn of the Moorilla winery, providing shade and a connection to the river without being immediately adjacent to it. On the day of the project’s opening, throngs of people gathered around and within the wall, sitting under the suspended oyster baskets that shade the lawn below. A key component of this project is the exhibition of the heavy metals that contaminate the Derwent – boxes containing mercury, lead, cadmium, copper and zinc have been embedded into the wall – but it also provides a home for the humble oyster, the river’s potential saviour. A huge communal table passes through the wall, suggesting an ongoing last supper to celebrate the river’s salvation.

The Heavy Metal Retaining Wall is the latest of the Monash University Art Design and Architecture’s (MADA) Design-Make projects, in which students design and build for a different site and context each year. This process seeks to bridge the gap between the traditional acts of design, typically occurring in the studio, and the acts of making on site. In this way, the program recognizes cross-disciplinarity and the blurring of design with construction and technologies: laptops are used on site, concrete is “printed” in the studio, builders become architects and vice versa. Last year’s project, the Stawell Steps, was an essay in the use of brick and I defer to Brett Seakins’s fine review and short history of the program.

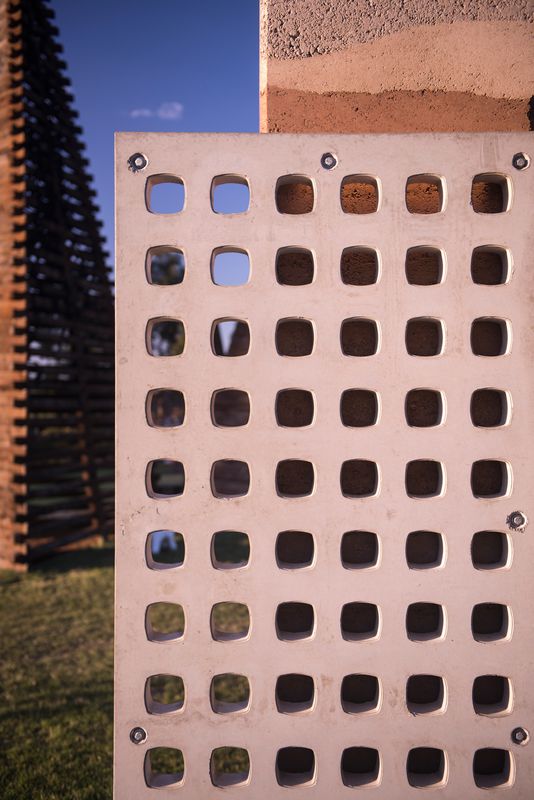

The Design-Make program has become more ambitious and complex since its first iteration in 2009 and for this project, third-year students were coordinating specialist trades as much as they were making things themselves. Whereas earlier projects constructed from timber were more directly workable with basic skills, here rammed earth and, in particular, the precast concrete involved the use of local trades. While the rammed earth has been formed on site, the waffle-like precast concrete panels were set with the aid of students using plastic beakers in a factory and then delivered to site. These two construction systems are laid side by side in the built work, the rammed earth walls visible through the holes in the concrete panels. Where these walls pull apart, the poché between creates a tomb, a Walshian space in which oyster shells lie underfoot. This tomb contains an installation by artist Kit Wise – a video link into live oyster baskets sitting off the nearby pier, the process laid bare.

Suspended oyster baskets provide shade.

Image: Jonathan Wherrett

The use of rammed earth in different soil types makes the wall a layered and tactile architectural object. It is hard not to read the soil, stratified into layers, as mountains, particularly with the surrounding hills of Glenorchy behind. The rammed earth reveals its making. The wall itself is inflected – cranking a couple of times to form enclosures and, perhaps, in a nod to the magnetic pull of Fender Katsalidis’s larger steel and concrete box that forms the museum, the undulating plan of which recalls both cliff faces and fortified towns. The retaining wall is ultimately a screen – protective, yes, but also providing a new front to the least engaging of the buildings on the estate, the Ether building.

Research into pollutants has revealed that oysters ingest and effectively clean the river of the heavy metals that pollute the Derwent. The Heavy Metal Retaining Wall is designed to encase these metals and the oysters farmed from the river nearby. The heavy metals are used in the construction of the wall in different ways: a zinc-clad box forms the main portal through the wall and frames a small shop, while a larger oxidized steel box forms a space in which food, including oysters, can be purchased. The other metals are used more sparingly: threads of mercury hang jewel-like in glass vials from a doorframe, a cadmium glaze has been applied to the tiles used in the oyster servery window and bands of copper mark the entry to the tomb. The oysters, meanwhile, will be removed from the river over time, slowly reducing the levels of pollutants in the river. These oysters will then be cast in glass and concrete bricks and inserted into the holes of the precast concrete panels, eventually closing up the tomb.

In its traditional sense, a retaining wall holds back land on one side in order to create a space on the other, but here the act of retention is broader: the wall will over time contain more of the heavy metals as they are removed from the river. For the MADA students, the experience gained here will be defining. The project has allowed them to be a part of, and gain a greater understanding of, the construction process – but it has also enabled them to break down the traditional barriers between those who design and those who make.

Credits

- Project

- Heavy Metal Retaining Wall

- Architect

-

Monash Art Design & Architecture (MADA)

- Project Team

- Ross Brewin (project architect), Alysia Bennett (project assistant), Andy Lim, Hang Jiang, Tess Wang, Piers Morgan, Lachlan Harris, Constance Mehel, Alexander McGlade, Nicholas Rogers, Anna Margin, Li Ren Tao, Brendan Murray, Mark Dower

- Consultants

-

Artist

Kit Wise (tomb ceiling), Biatta Kelly (mercury vials), Zsolt Faludi (cadmium tiles)

Basket and shell suppliers Tasmanian Oyster Company

Concrete and steel Stephen Little Constructions

Engineer Peter Felicetti

Lighting MEGS Lighting

Project curator Kirsha Kaechele

Project manager Steve Devereaux

Rammed earth Unique Earth

Table construction Aedan Howlett

Timber Cordwell Lane Builders

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Type Small projects

Source

Project

Published online: 8 Oct 2014

Words:

Stuart Harrison

Images:

Jonathan Wherrett,

Rémi Chauvin

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2014