Photos Richard Eastwood

A city’s heritage value results not so much from the quality of individual buildings, but from a layering of built fabric that reflects the ideals and ambitions of each distinctive phase of history. This is not a new idea and it is one that is largely supported in relation to well-loved periods of Australian built history – principally Georgian, Victorian, Federation, and (more recently) Art Deco.

Post World War II work, on the other hand, is not well loved. There is a slip in the way we value work of the 1950s and 1960s.

This was a period of optimism, of the beehive hairdo. It was a brave new world recovering from the atrocities and bleakness of war. It was a time when history was spurned because the war (or the failure to recognise its genesis) was seen as a result of belief systems with roots in that history; a time when, buoyed by wartime experiences of systematised building and planning, it was imagined that the world might be entirely reconstructed in a new image. In such circumstances it was possible to conceive of a “green-fields” approach to urban renewal. That is, it was possible for planners to imagine that the complete obliteration of existing fabric was a positive initiative, making way for the symbols and instruments of new beginnings designed to bury old evils in a kind of historical amnesia.

In hindsight these attitudes appear naive and the built results often ill considered – offensive marks in otherwise attractive period streetscapes. The approach was indeed flawed and our contemporary heritage-responsive sensibilities would be appalled should a “green-fields” approach be proposed today – unless of course the buildings in question were from the 1950s.

The Tasmanian Environmentally Sustainable Housing Architectural Design Competition for Windsor Court in Hobart is a recent example of such a proposal. Here heritage issues are complicated by a contemporary (and proper) concern for environmentally responsive design.

Unfortunately the adjudicators have made it clear that preservation of the existing built fabric is not an option. It is to be demolished and a “green-fields” site assumed. It is astounding that neither the complex heritage issue nor the equally complex ESD issue (both relating to the possible retention of the existing fabric) are included as the principal subjects of the competition. For this reason the competition is unlikely to attract entries from Tasmania’s more innovative architects.

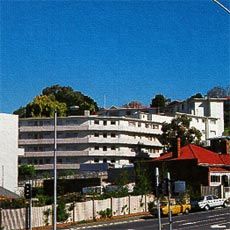

Windsor Court is a largely intact example of postwar attitudes enshrined in the concrete forms of a series of residential blocks, accommodating some 50 units. Like much of Australia’s best architecture from this era, it was designed by an emigre architect – Englishman Wilfred Bell for the Housing Department.

Hobart is now perilously close to losing much of its building stock from this era and a number of key buildings have already disappeared. At the Hobart Railway Station a Georgian building was kept in an ABC development, while the glazed-tile Moderne building and its attendant platforms were removed. Across the road, in the Wapping redevelopment, a misguided sense of urban consolidation has led to the proposed demolition of the Transport building. The iconic dive tower of the old Olympic Swimming pool was demolished to make way for the new Hobart Aquatic Centre.

These buildings were part of a greater collective of postwar buildings centred on the roundabout fountain. In conjunction with others, such as Windsor Court, they tell (or told) us much about the period, its attitudes and ambitions. This situation is typical of Australian cities.

The individual heritage value of these buildings has not warranted their inclusion on the National Register. This means that they are all too easily removed. However, the lack of a heritage listing does not mean this fabric is unimportant. Rather, it opens up a significant opportunity – one of radical modification – that would result in something entirely new, within which the trace of the old might still be found. Such an approach also respects the basic sustainable principle of recycling rather than replacing existing fabric in order to reduce embodied energy. The unqualified decision to demolish Windsor Court suggests that political, rather than sustainable, agendas are driving decision making processes.

These perhaps arise from era bias rather than an understanding of the potential layering of cities.

This layering is not about replication or even deference to existing forms (a common misinterpretation in Australia). Instead it is about developing a positive relation between each new layer and its predecessors. The key point in all of this is that the urban landscape is not solely about historic preservation or, what we commonly see in Australia, era bias – that is, the precedence of Georgian and Victorian over every subsequent era. Rather it is about the considered modification of constructed environments for the purpose of adding new layers to an already rich urban fabric. It is time to revalue this period, and to find ways in which its built evidence might be usefully retained as a rich layer in the continuing development of the city.

It is not clear how the proposal to demolish Windsor Court differs from the historical amnesias of the postwar period (the results of which, ironically, are to be erased). Indeed, the government has not entered into debate on the issue, even through the competition question process.

To propose such a demolition, in our own period, and particularly under the guise of a competition claiming to encourage innovation, is naive. Although the competition name suggests a principle ESD focus, its basic tenets reveal a lingering modernist ideal of demolition and “greenfields” sites. The end result will be an idealist solution devoid of the gritty reality of having to deal with the existing structures and their stories, the stuff of which real heritage is born.

Richard Blythe is deputy head of the School of Architecture, University of Tasmania, and a partner of Reinmuth Blythe Balmforth terroir