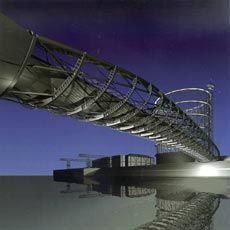

The bridge design takes its cues from the redundant industrial structures – a gasometer and a gantry – adjoining the site.

The elements of the bridge.

The recent competition entry by the ›› Melbourne based practice of Robert Watson ›› Architects for the Due Ponti Pedonali Sul ›› Tevere competition in Rome provides an ›› opportunity to again consider urbanism, ›› architecture and engineering in relation to ›› the provision of infrastructure projects.

It is shared wisdom among urban ›› designers that infrastructure projects now ›› dictate the direction of urban development, if ›› not the transformation of our cities, and that ›› infrastructure project budgets dwarf the ›› capital allocated to building procurement. It ›› follows, then, that urban design must engage ›› with such projects, first to achieve qualitative ›› improvement in our cities and second to ›› fund urban design itself.

In some places a consensus has been ›› reached: that the design of infrastructure is ›› to be valued, and that it should take place ›› out in the open. Bridges were perhaps the ›› representative image of architecture in the ›› 1990s. Old debates as to engineering or ›› architecture had passed, and, at an aesthetic ›› level, the bridge had evolved from a purely ›› technical or engineering problem to an ›› object of experimentation and a verification ›› of new architectural and urban values. In ›› such places the judging of a competition ›› for pedestrian bridges might now centre ›› on the design of bridges as public space, ›› rather than as an autonomous object, or ›› even an emblem.

A working proposition might best see the ›› bridge as part of the city, and as a public ›› space itself. This combines the need to unite ›› separate places with the morphological ›› autonomy typical of (most) bridges.

The single-stage competition for the Tiber ›› bridges invited entrants to submit designs for ›› one of two bridges, the Ponte Della Musica ›› and the Ponte Della Scienza. The brief called ›› for simple solutions, easily adaptable to ›› diverse and complex uses. It required ›› originality of structural thought, and ›› responses to a range of urban and ›› environmental factors. Further, it set specific ›› and detailed criteria for the design and ›› testing of the bridge, and it imposed ›› technical limitations on supports above and ›› below the low water channel.

The brief also implicitly acknowledges the ›› regenerative power of the bridge. The Ponte ›› Della Scienza – for which this design was ›› entered – will restore continuity between two ›› ex-industrial areas. The Ostiense or eastern ›› bank is notable for the presence of large, ›› unutilised industrial structures. Under the ›› Progetto Urbano Ostiense – Marconi master ›› plan, the bridge is a nodal point for a network ›› of open spaces, walkways and cycle paths.

The design takes its cue from redundant ›› gasometer and gantry structures adjoining ›› the site. Formally, it is a lyrical demonstration ›› of horizontal mobility, the bridge being ›› less a place to view the surroundings from, ›› and more a celebration of arrival and ›› departure: the structure gathers momentum ›› as you cross, and dissolves or falls away ›› on departure.

At another level, the bridge tests its ›› underlying structural proposition, described in ›› the competition entry as an “elongated, ›› annulated structural tube”. The lattice tubular ›› form is cut away dramatically at each ›› embankment, reading as an assembly ›› stretched near to its limit and only tenuously ›› attached at the abutments. There is also the ›› apparent dichotomy of the straightforward ›› plan geometry and largely static composition ›› of the bridge elements, which, when ›› juxtaposed with the curvature of the rings ›› and the bowing of the deck, gives a dynamic ›› quality to the overall structure and an image ›› of great tension.

In concept, the structure is a simply ›› supported steel tube spanning some 108 ›› metres; in fact, it is an assembly of distinctly ›› articulated structural elements, prefabricated ›› in parts and fabricated into sections for ›› lifting into position.

A series of elliptical rings – the form of ›› which is generated from the different ›› profiles of the inner and outer flanges and ›› connected by a series of cross struts – are ›› essential to the concept. The rings are set at ›› four metre centres and are connected by a ›› lattice of diagonal members to create a fully ›› braced frame. Five primary cables are laid ›› out at the bottom of the rings. Acting as a ›› tension chord, they are anchored back to ›› abutments at the springing points.

At each end of the bridge the rings are ›› cut away to form a chamfer, to which are ›› attached large compression yokes ›› transfering loads to the abutments. A ›› diagonal lattice of compression members ›› completes the “top chord” of the tube.

Finishing the bridge assembly is the ›› pedestrian deck. Framed as a grille of steel ›› beams, the deck spans between, and is ›› propped off, the bottom of the rings, so that ›› it appears to float clear of the framing of the ›› tube along its length.

To return to the proposition of the bridge ›› as both public space and autonomous ›› object, it is instructive to look at the design ›› in relation to each of these issues.

The first issue is the formal reading of ›› the structure of the bridge. The competition ›› entry indicates a didactic relationship ›› between structural action and the diagonal ›› lattice; that is, the sizing of members is ›› based on the forces they must carry. In real ›› terms this generates lattice elements ›› ranging in size from 90 to 400 mm. At issue ›› here is the merit of demonstrating the forces ›› at play versus the dominance of, or balance ›› between, the lattice and the rings in the ›› overall image of the bridge.

The second issue is the role of the bridge ›› as public space. Is it sufficient, as the ›› submission suggests, to provide for ›› conversion as a temporary pavilion or ›› exhibition space? The method is to “skin” ›› the bridge in a translucent fabric, providing ›› sealed access and egress and servicing the ›› space from within the deck. Or, does the ›› solution lie in the methods of illumination ›› proposed for the bridge? Perhaps here one ›› might need to go beyond static illumination ›› to sequenced or kinetic effects, without ›› compromising the architectural intent.

As always, in the case of a competition, it ›› is the designer’s call. However we can ›› appreciate that projects of this quality ›› demonstrate again the possibilities for ›› infrastructure design and alert architects to ›› the wider opportunities for their work.

Ross Ramus is principal of Ross Ramus ›› Architects and a lecturer at RMIT University.

The competition entry was developed in ›› collaboration with Venelli Kramer Archetti, ›› Rome, Ove Arup & Partners, New York, and ›› cost consultants Tim Gatehouse & ›› Associates Ltd, London