Caroline Butler-Bowdon and Charles Pickett outline the neglected history of apartment living in Australia.

Northbourne Housing complex for the National Capital Development Commission, 1962, by Ancher, Mortlock and Murray. Image: Max Dupain, 1966.

The Astor, Macquarie Street, Sydney, 1923, by Donald Thomas Esplin and Stuart Mill Mould. Image: Eric Sierins, 2006.

Beverly Hills, Darling Street, South Yarra, by Howard Lawson. Image: Eric Sierins, 2005.

The Albany, by G. M. Pitt, 1905. Image: Milton Kent, 1925. City of Sydney Archives.

Ithaca Gardens units, Elizabeth Bay, 1960, by Harry Seidler. Image: Max Dupain, 1960. © Penelope Seidler.

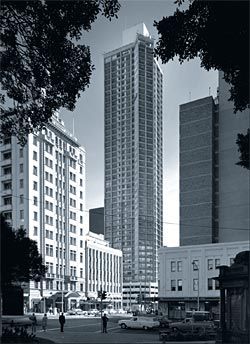

Park Regis units, Park Street, Sydney, 1968, by Stocks and Holdings (later Stockland Trust). Image: Max Dupain, 1968.

Kingsclere, Greenough Avenue, Sydney, 1912, by Maurice Halligan and Frederick Wilton. Image: Eric Sierins, 2006.

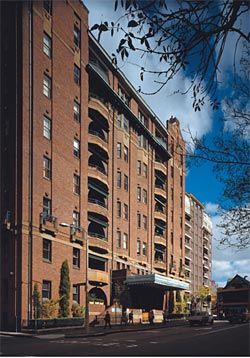

Torbreck, Dornoch Terrace, Brisbane, 1958–62, by Aubrey Job and Bob Froud. Image: Eric Sierins, 2006.

Poets Corner, 1966, by Peddle, Thorp and Walker for the NSW Housing Commission. Image: Max Dupain, 1965, “Housing Commission unit blocks, Redfern, under construction”.

Flats have always been a minority dwelling form in Australia, but for most of the twentieth century flat living was a popular alternative to the suburban cottage. At mid-century flats accounted for almost one fifth of occupied dwellings in Sydney. Today a third of Sydney households live in medium- and high-density housing, while apartments form significant minorities of Melbourne and Brisbane’s dwellings. And more flats than houses are being built in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane. Urban demographers predict that within 30 years, 45 percent of Sydney households will be living in flats.1

Yet Homes in the Sky is the first history of apartment design and living in Australia. As architect Peter Brew wrote: “Flats and their architects remain outside official histories … Flats pose a problem for our invariably nationalistic historians because they do not affirm the egalitarian myth of the nuclear family with Hills hoist and mortgage.”2 In reality, apartments have a longer Australian history than majority home ownership, the “Anzac Legend” and many other touchstones of national identity.

Since purpose-built apartments first appeared in Sydney and Melbourne a century ago, they have been at the centre of an ongoing debate, and much more was at stake than aesthetics and convenience. To many Australians, the future of the nation was in the balance. Throughout the twentieth century, apartments were described as “the slums of the future”. However, apartments also had proponents and enthusiasts. In 1912 Professor Robert Irvine of Sydney University was sent by the New South Wales Government to investigate workers’ housing in Europe and the USA. He reported:

“New Yorkers, it seemed to me, have grown to love the life of the city, its brilliancy, its crowds, its pleasurehouses … They have suffered the tenement-house system to grow to its present proportions because, on the whole, they preferred it; and I should imagine they would be rather unhappy in our sparsely-peopled suburbs where life is quiet and beautiful enough, but extremely dull and petty … For the same reason, many people in Sydney are now crowding into boarding and apartment houses.”3

During the first decades of the twentieth century, “mansion flats” sprang up on Sydney’s Macquarie Street and Melbourne’s Collins Street, before escalating city land prices saw wealthy inner suburbs (Potts Point, Elizabeth Bay and Kirribilli; South Yarra, Toorak and St Kilda) remade as apartment precincts. Most press commentary on Australia’s first mansion flats was positive: “the ‘flat’ is a self-contained home in miniature, where the tenants share only the lift and stairs in common. Once inside his own entrance door each is shut off from his neighbour as much as he could possibly be in any house that is not quite detached.”4

Early city flats included The Albany, Strathkyle and Wyoming, Melbourne Mansions and Alcaston House and most combined professional suites with residential accommodation. However, the future in luxury apartments was announced in 1912 with the completion of Kingsclere, the first of many apartment towers to be built in Macleay Street, which runs along the Potts Point ridge, establishing Kings Cross as Sydney’s main apartment precinct. Kingsclere introduced the American style of apartment block, and during the decades following its completion in 1912, Kings Cross saw the same design formula used for Kingsclere’s progeny, including Byron Hall and Selsdon, culminating with Cahors, Birtley Towers and the Macleay Regis.

Kings Cross flats were built primarily on sites created by the demolition of colonial and Victorian terraces and mansions, or by subdivision of their grounds. “Famous families had their homes there, usually in spacious grounds. Some of the old homes are left. But many have gone and the land, now subdivided, is occupied by flats.”5

Instead of the perimeter block apartments that pioneered city apartments in Europe and England, the Kings Cross apartment boom of the 1920s and 1930s was shaped by the existing townscape and available building sites. What could have been a social and aesthetic disaster was ameliorated by the urban character of Kings Cross and its layering of new and old buildings of different functions and styles, both architecturally and socially. Out of this diversity came the social legend of Kings Cross, created primarily by the numerous artists and writers who made the district their home.

In Melbourne, the respectability of near-city apartment living was enhanced by the involvement of high-profile architects including Walter Butler and Walter and Marion Burley Griffin. “Within the past few years there has sprung up an increasing demand for a better class of flat, and in the near suburbs of Melbourne, such as St Kilda, South Yarra and Toorak, it is found that flats of a luxurious order are being built, flats that are designed on expensive lines, and that have all the privacy and individuality of a home.”6

Most of the new buildings were of two or three storeys, with extensive landscaped grounds. As Building observed: “In Sydney, the tendency in the recognised flat areas is to erect multi-storied blocks, complete with elevators and all modern conveniences … In Melbourne, on the other hand, we find the question approached in a somewhat different fashion, the blocks seldom being more than two storeys in height, and stretched horizontally rather than vertically …”7

That flats in South Yarra and Toorak blended almost anonymously into respectable streetscapes was in part a response to the strength of anti-flat opinion in Melbourne, reflected in council by-laws which limited apartments to two or three storeys throughout most of the affluent inner-eastern suburbs. In contrast to Kings Cross and Potts Point, South Yarra and Toorak retained their identity as exclusive suburbs.

Meanwhile, apartments broadened their geographical and social market, invading seaside and less affluent suburbs. They also gained a presence in other cities, notably Brisbane and Perth. Despite their critics, flats were eagerly sought after, averaging higher rentals than houses during the 1920s and 1930s. Before the introduction of strata title laws during the 1960s, the association between apartments and rental tenancy heightened their distance from the social ideal of home ownership. A typical complaint came from Ku-ring-gai Alderman McFadyen: “The flat dweller belongs to the floating population of the big cities and is of no value to the community, as a flat is not a home.”8

During the 1930s, exposure to European Modernism at its peak of achievement and credibility telescoped the interval between international developments and local practice. Architects including Best Overend, Morton Herman, Dudley Ward and Geoffrey Mewton returned from European sojourns and translated forms devised for European social housing into the Australian private market. Apartments formed the cutting edge of Australian Modernism. From the 1950s, émigré architects and developers brought apartment modernism to the masses, although it was often fatally compromised by building laws devised for suburban cottages.

Walk-up flats, especially, represented the accommodation of the apartment format to Australian suburbia. Official denial of the functional differences between single- and multi-unit dwellings had many consequences. It allowed apartment development to be accommodated to the existing street and subdivision patterns, but it also limited their architectural, urban and living potential. In a sense the “Australian dream” took its revenge in this suburbanization of apartments, simultaneously ensuring that their image was forever compromised.

Although walk-ups on single blocks are no longer built, they remain a troubling urban legacy, and are often the only accommodation available for those on the fringes of the housing and labour markets. A similar fate may await the new blocks encouraged by urban consolidation policies. The academic and urbanist Bill Randolph argues that “a highly mobile population of youthful tenants may not be a secure base on which to rebuild declining town centres …”9

Public apartments form another difficult legacy, underlining the striking difference between the social and political success of private and public apartment towers. Architecture embodying social status and exclusivity quickly became, when built for public tenants, a symbol of exclusion and disadvantage.

In recent decades a new acceptance of apartment living has emerged. City apartment living has regained its social cachet. Governments have formed frequently unholy alliances with developers, making apartment complexes the centrepiece of urban change. Apartment controversies are now focused less on family life and morality than on heritage and urban aesthetics. As apartments have become part of the housing mainstream, Homes in the Sky signals their integration within Australian architectural and urban history.

Dr Charles Pickett and Caroline Butler-Bowdon are authors of the book Homes in the Sky: Apartment living in Australia (The Miegunyah Press, an imprint of Melbourne University Publishing in association with Historic Houses Trust); and the exhibition Homes in the Sky: Apartment living in Sydney at the Museum of Sydney from 12 May to 26 August 2007.

Walk-up flats at Brighton-le-Sands, 1960s. Image: Eric Sierins, 2006.

1 B. Randolph, quoted in Mary O’Malley, “Storm clouds ahead: the cities of our future”, Uniken 28, October 2005, p. 8.

2 Peter Brew, “Modern flats”, in Simon Anderson and Meghan Nordeck, Krantz & Sheldon Architectural Projects (Perth: University of Western Australia, 1996), p. 5.

3Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the question of the Housing of Workmen in Europe and America, (Sydney: Government Printer, 1913), pp. 98–99.

4Art and Architecture, August 1905, pp. 120–121.

5Sydney Morning Herald, 10 November 1937, p. 16.

6 “A new and handsome two-flat home”, Australian Home Beautiful, October 1927, p. 18.

7Building, August 1938, p. 25.

8Hornsby Advocate, 7 June 1929.

9 Bill Randolph, “The haves and have nots do not meet in the new suburbia”, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 May 2004, p. 17.