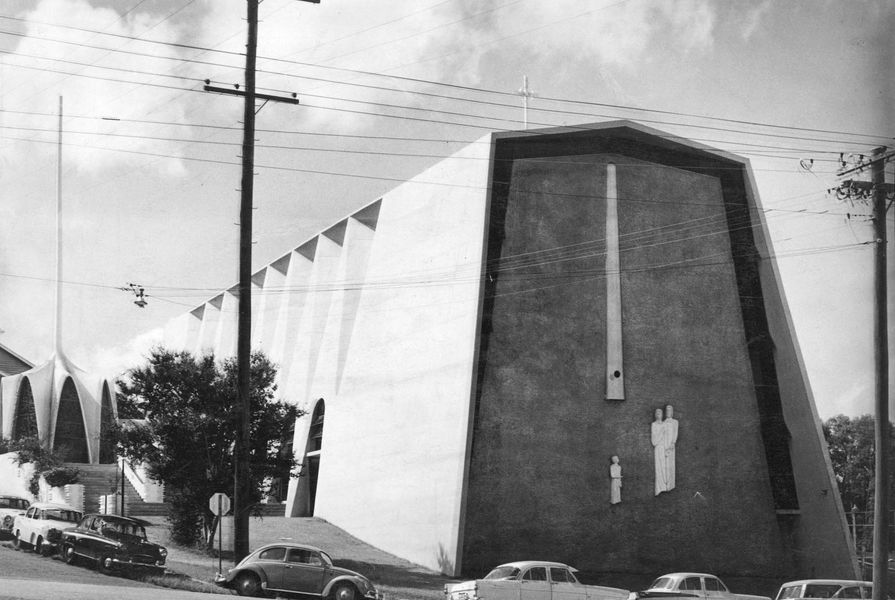

The Holy Family Catholic Church in Indooroopilly was designed by the Brisbane-based architectural firm Douglas and Barnes in 1961, and constructed between 1961 and 1963. Noticeably influenced by Pier Luigi Nervi’s unrealized scheme for a cathedral at New Norcia, Western Australia (1957–61) as well as other, international modern concrete church designs – most notably Marcel Breuer’s St John’s Abbey Church in Minnesota, USA (1953–61) and Oscar Niemeyer’s chapel at the Palácio da Alvorada in Brasília, Brazil (1958) – it combined expressive forms with novel materials and relied on innovative construction methods that had never before been tested in Queensland.

Holy Family was built at the height of church construction in the state. Between 1955 and 1965, more churches were built in Queensland than in any decade prior or since. In this period, the Catholic Church and its architects also increasingly recognized the need to rethink ecclesiastical architecture to cater for modern society. However, the Liturgical Movement’s progressive ideas for liturgical renewal, formalized by the Catholic Church as part of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), are not evident in the design of Holy Family.1 Its vertical structure and elongated basilica were firmly rooted in pre-conciliar attitudes. Nonetheless, Holy Family is arguably one of the most expressive and memorable modern churches in Australia. It should enjoy greater national recognition, and certainly deserves better protection and care.

In 1960, Archbishop James Duhig, also known as “James the builder,” purchased the corner block adjoining the existing timber parish church in Indooroopilly, which had been built around 1926. Following this land acquisition, parish priest Father Victor Francis Roberts (Indooroopilly PP 1938–73), to whom Duhig entrusted the management of the project, travelled to Europe to visit the latest Catholic churches. Upon his return, inspired by what he had seen overseas, Roberts commissioned the young local architect William (Bill) Douglas of the firm Douglas and Barnes to design a modern architectural landmark.

Holy Family features complex, expressive geometry contained within a more traditional vertical structure and elongated basilica.

Image: SLQ RAIA Photography Collection

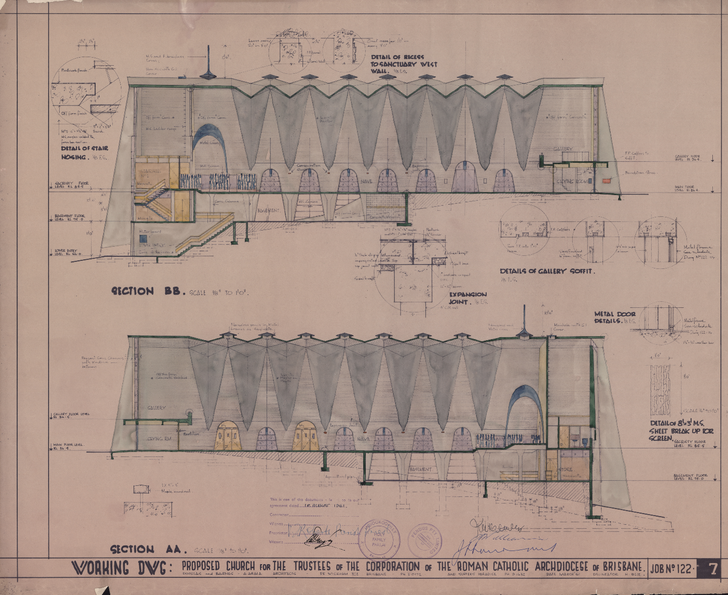

By mid 1961 the design was complete. Douglas had dreamt up a monumental church of tilted walls with origami-like pleats. The imposing column-free concrete structure measured 51.8 by 14.3 metres, and reached 17.5 metres at its highest point. Inside, it offered seating for 615 people. The design of the baptistery chapel, which was separated from the main building, was a geometrical tour de force. It was octagonal in plan and had eight tilted hyperbolic paraboloid arches as walls, a sculptural ceiling of curved pleats that masterfully joined the arched bays together, and a tall slender spire.2

To document this extraordinary design, the architects relied on complex mathematical formulae and geometries (calculated and drafted by Harvey Blue, an employee of Douglas and Barnes). For instance, the eight hyperbolic paraboloid arches of the baptistery chapel were calculated and set out using conic sections. The fact that these walls were also tilted inwards by ten degrees added further complexity to the calculations.3

The complex design resulted in a challenging build, and construction took more than two years. Requiring non-standard construction methods and locally untested techniques, Holy Family was a test for the workmen involved, which is likely why the first contractor went bust. A local boat builder was engaged to construct the timber formwork for the chapel, and for the church building proper a scaffold tower was constructed. The tower was supported on “bogies” (wheel sets used under train cars) and slid on rails down the centre of the building. “Jumbo,” as it was called, supported a collapsible “butterfly-like” formwork that allowed the contractor to pour one “pleat” of the church at a time.

Sections and floor plan, prepared in March 1961.

Image: University of Melbourne, Fryer Library Douglas and Barnes Collection, UQFL289 job0122.

In the final construction phase, the buildings were coated externally with Plastevic, a glossy vinyl paint, in a very light shade of green. Roughcast stucco was used for the western facade, which was painted gold. The building’s pleated interior was then sprayed in acoustic plaster, which contained finely ground stone additives. A copper painted reredos and altar canopy (a metal civory or ciborium), marble altar and pulpit, and brass ecclesiastical pieces furnished the sanctuary. Each of these finishes added gloss and sparkle to the architecture.

In total, the building cost more than £70,000 (approximately $19 million today). And so, it became not only one of the largest, but also one of the most expensive, Catholic churches to be built in postwar Queensland.4 Part of the extensive budget was spent on modern artworks. Roberts commissioned three progressive artists to design sculptures, frescoes and coloured-glass windows for the complex. In close consultation with the architects, Raymond Austin (Ray) Crooke painted the Stations of the Cross directly onto the interior walls of the worship space. Erwin Albert Guth hand-crafted two sets of sculptures – one for each street facade. The Holy Family , depicting Jesus as a child looking towards Joseph and Mary, was positioned on the west facade, while Finding of the Child Jesus in the Temple , which showed Joseph with Mary holding the infant Jesus, adorned the north facade of the building. Finally, Andrew Sibley was invited to produce seven dalle de verre5 windows for the baptistery chapel; each depicts one of the seven sacraments. These works were all commissioned early on in the documentation stage, mainly through Blue’s connections with Brisbane’s Johnstone Gallery.

Holy Family is one of the prime examples of church building of the early 1960s. This was a pivotal time, when church architecture in Australia increasingly aspired to express in form the aggiornamento (modernization) initiated by the Catholic Church, while still holding fast to some of the vestiges of the traditional, representational church. With its reinforced concrete walls and technically challenging construction methods, Holy Family pioneered ideas of modern architecture in Australia.

Sections and floor plan, prepared in March 1961.

Image: University of Melbourne, Fryer Library Douglas and Barnes Collection, UQFL289 job0122.

Today, more than fifty years later, the current congregation (very commendably) has taken on the responsibility of repairing and conserving its landmark church. This significant, challenging and costly task should, however, not fall only on a small group of people, but should be carried by the architectural community of Queensland, and the state’s heritage department.6 Holy Family Catholic Church is a community asset, embodying many memories of a time when religion was held in greater respect by Australian society, and when church design, “modern” religious art and experimental “modern” architecture were all at their peak.

– Lisa Marie Daunt worked as an architect for fifteen years before returning to the University of Queensland in 2016 as a PhD candidate. Daunt’s research centres on Queensland’s postwar church building designs and critically analyses context, influences, trends and exemplars.

Author’s note

This article includes reworked parts of Lisa Marie Daunt, “Modernist Concrete: Technologies of Brisbane Church Architecture in the 1960s,” in Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, Michael Dudding and Christopher McDonald (eds), Historiographies of Technology and Architecture: Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians of Australia and New Zealand (Wellington: SAHANZ, 2018), sahanz.net/wp-content/uploads/SAHANZ18_Proceedings-2-red.pdf (accessed 10 February 2019).

Footnotes

1. For further reading on the Liturgical Movement, see Rev Peter Hammond, Liturgy and Architecture (London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1960) and Robert Proctor, Building the Modern Church: Roman Catholic Church Architecture in Britain, 1955 to 1975 (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2014).

2. The University of Queensland, Fryer Library, Douglas, Daly and Bottger Collection, UQFL289, job0122.

3. Harvey Blue, interview with Lisa Daunt, 17 April 2017.

4. The Catholic Leader , 16 November 1961 and 14 November 1963.

5. Chunks of coloured glass cast into a concrete resin.

6. Currently protected by a Brisbane City Council local heritage listing.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 28 Oct 2019

Words:

Lisa Marie Daunt

Images:

SLQ RAIA Photography Collection,

University of Melbourne, Fryer Library Douglas and Barnes Collection, UQFL289 job0122.

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2019