Reality has its bitter twists. It is not all sunshine, even in Australia. Toward the end of 2010 and in early 2011 vast areas in the north were destroyed by severe floods. What would be the ideal response of architecture in disastrous times like these? Houses afloat like boats, or transforming themselves into submarines, or taking off like balloons to land somewhere safe? Utopia? Possibly, but maybe not.

Built by Tribe Studio.

Dreams of moving, flying or floating houses are nothing new. Few have been realized. But they still encourage us to reflect and to think ahead about architectural problems. In February this year, the Boutwell Draper Gallery dedicated an extensive exhibition to the theme of Home – Real and Ideal. Nineteen artists from the gallery met up with nineteen architects from Sydney. Because curator Piero Chiefa kept the brief largely open, there were no specific objectives limiting the theme. Everything was possible – from visionary leaps to ideas dealing with sustainability, from new solutions for conventional building types to futuristic concepts. As a result, there was no connection in this mixture of ideas. No dialogue or teamwork took place. Architects and artists were presented side by side – each on their own.

Many architecture practices took the opportunity to present their latest work, hand in hand with the ideal version they would have liked to see if the budget had been sufficient, the client more understanding, the engineering more advanced or the site more beautiful. Luigi Rosselli, for example, presented his Six Degrees of Separation house in Gordon’s Bay alongside a lost and found bin with projects that have been shelved or lie in waiting. Collins and Turner presented the real and the ideal elevations of its Coutts House in Balmoral Beach. In reality, the house consists of a cluster of white picture frames, which serve a variety of functions, including the framing of views. Its ideal version shows dissolving structural walls and slabs. The interior melts into the sea and the sky. Merging architectural elements with nature to arrive at the ideal dwelling is also what interests David Boyle. His contribution to reality was the Burridge-Read Residence on the central coast of New South Wales. In his ideal development everything is stripped down to footbridges, paths and platforms, carefully placed in the bushland. Welsh + Major, too, would have liked to hang in the trees and relax, but faced reality with a recently completed project in Enmore.

Surprisingly, the majority of participating architects sought a dialogue with nature in the exhibition. Australia’s population is about 92 percent urban. There are four million inhabitants in Sydney. What are the ideal urban answers? Does it make sense to be exposed to the elements, for the walls to start to deteriorate, when the traffic is roaring outside? Why is the house situated in unspoiled nature still our ideal? Is this not unrealistic? For how does the common Australian get home? By car! The car is part of living culture. And here we come to an end regarding our ideal of unspoiled nature.

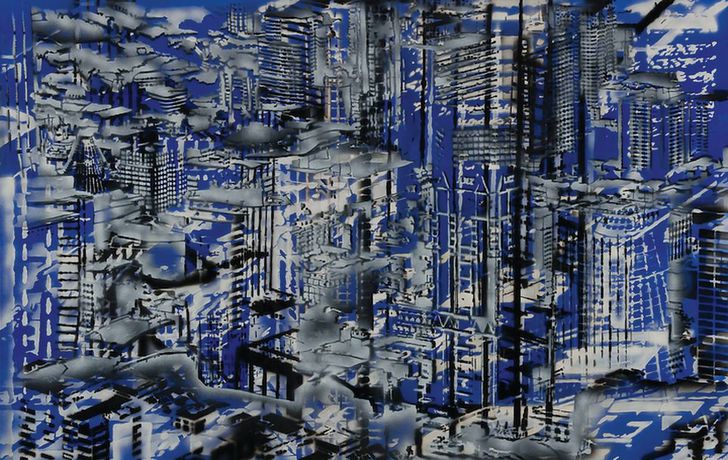

Electrifying by Louise Forthun – a dense field of structures becomes a cityscape.

The most powerful urban vision of the exhibition was Louise Forthun’s painting Electrifying. It is dense, full of structures, forming a cityscape. Light horizontal fields of clouds seek reconciliation with vertical elements. The painting thus poses current questions about themes of the city such as building, growth, migration, economics, politics, gender and nature. What are the strategies for a better built environment, what potentials should be invigorated, which conventions should be questioned, where can we make compromises, where should we start anew? What approach could be trendsetting? How does the city of tomorrow appear?

Some architects followed up on those problems in the exhibition. Stanisic Associates presented a massive urban block, Hyperform, which supports a tendency for density and attempts at the same time to reorganize urban exteriors. Levels of different qualities are being stacked, opened up and rearranged. Stanisic thus remained close to reality and did not break any conventions, unlike DRAW. With its Momentary House built out of Lego blocks (in fifteen minutes), DRAW was clearly questioning architectural durability, settledness of inhabitants, form, colour, connection and technical possibilities. It would have been interesting to see a concept model like this actualized at an urban scale for a specific site in Sydney. Another interesting approach was that of Tribe Studio. There are no obvious walls in its vision of the ideal living space, only two small windows. It is a life in two worlds. The city outside and the residential inside. The connection is minimal. The dividing element is soundproof, opaque, without form or colour. Similar in its radicalness was the project Coraline Cities by Innovarchi. It could be the answer to the next flood: structures of renewable, coral-like material can be generated both below and above water. It is also a material with the ability to grow and to adapt to changing conditions.

Imagined Landscape by David Boyle – development stripped down to footbridges, paths and platforms.

But what should be changed? How do we want to live in the future? Is the standard type of open living (including kitchen, dining and living room), separate bedrooms and one bathroom per bedroom, if possible, ideal? (There are hardly any exceptions to this scheme being built in Australia.) The exhibition did not provide answers to these questions. An intense discourse on visions of an urban future, analysis of our current situation and questioning our approach to work and work processes would have been helpful if undertaken beforehand. The results would certainly have come out in a more significant, possibly visionary or even revolutionary manner.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 2 Aug 2011

Words:

Claudia Perren

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2011