<b>REVIEW</b> LIAM YOUNG <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> RICHARD STRINGER, RICARDO FELIPE

The verandah of the Watson House curving around the convex edge of the horseshoe form, with the open landscape beyond. Photograph Richard Stringer.

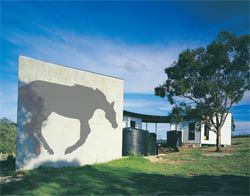

The house under construction, showing the clearly figured plan form. The blade wall of bagged concrete block at one end will host the horse mural.

View from the house across the site in a semi-rural valley on the outskirts of Brisbane.

Looking east to the courtyard and deck, with the applied image of the horse on the entry wall. Photograph Ricardo Felipe.

North elevation. The office is behind the balcony, with the studio tucked underneath. Photograph Richard Stringer.

CLAUDE-NICOLAS LEDOUX asks if there is “anything that should not be capable of offering to the eyes the attraction of useful progress”. In response he reflects on the literal form of his Coopers’ House and Workshop, a seemingly “unimportant” small building in a little-frequented forest that became a vehicle for debate and questioning the architectural sensibilities of the eighteenth century. The Watson House, by NMBW’s Queensland office, is a modest project of 140 square metres situated in a quiet semi-rural valley on the outskirts of Brisbane. Through a deliberate engagement with the unfashionable motif of the figural plan, the house weighs into the debate on the relationship between plan form and experience in the context of the history and culture of Australian rural housing. This exploration of the figural plan, applied image and experience also underpins recent speculative research by the project architect Andrew Wilson. As implemented here, these strategies have a particular resonance as the house is juxtaposed with familiar and “comfortable” semi-rural housing models established on newly subdivided farms and grazing land in the Samford Valley. The first stage of the Watson House is complete. A second phase will extend the project’s emblematic “horseshoe” plan form.

The house sits at the high end of a five-acre horse property that slopes gently to a creek running along its northern boundary. Surrounding the site is a further subdivision of open paddocks extending to the foot of the mountain ranges that enclose the valley. An oblique, aerial view of the house from the high ridge of an approach road provides its initial image: something “other than”, a radial white object in a field, an imprint of the figural, horseshoe form. This first instance reveals a gestalt view of the plan, a precise and instantaneous understanding that is not available from the ground. The grounded knowledge that a figure generates the built form comes later, through experienced walking around and through the building. Any position occupied in the figured plan is understood through the oscillation of the concave and convex walls of the house. A knowing subject is able to use and accommodate this awareness of the complete and consistent form with the unpredictability of the experiential.

On entry, the equine imaging of form and of programme are reiterated. A solid blade wall of bagged concrete block, finishing one end of the form, is emblazoned with the painted silhouette of a galloping horse. The reduction of detail and the simplicity of the image allow the mural to work as an architectural device at the scale of the building. The emblematic plan figure and the applied image provide a literal confirmation of the property’s programme – a playful exchange between geometry and purpose. Ledoux appears to be a reference in NMBW’s toying with literal representation. The Coopers’ House and Workshop encompassed a figural geometry of intersecting curves, hoops and barrels – the coopers were surrounded by the shape of their craft. This game plan, encompassing a play between architectural and pictorial signs, is also evident in NMBW’s figural form.

Moving toward the entry courtyard of the Watson House, the scale of the object viewed from a distance is maintained. A good deal of contemporary Queensland architecture attempts a tectonic informality. Often a process of “addition” serves to disguise the logic of form and function. In contrast, this house demonstrates a commitment to form. The shaping of the elevations reinforces this bold statement and the ambiguity of scale distinguishes the Watson House from the surrounding built environment. Through a process of erosion, fragments of the figure are strategically cut away, opening the interior spaces to the outside and mediating the viewing subject’s experience of the landscape.

The two end walls of the horseshoe frame the opening of a courtyard. Here the enclosing, faceted concave wall captures a protected fragment of the landscape, an attendant tree and water tanks. Steps lead to an open breezeway as entry deck, made possible by a simple erosion of segments of the form. This station point provides a privileged platform for reading the two different relationships to the landscape afforded by the figural plan. A view back to the west, through the courtyard and out to the sky is framed by the bottom edge of a black rubber fascia that wraps around the complete concave line of the form. This fragment can then be read against the wider and distant eastern vista seen through the convex slot created by the open breezeway. The verandah on the convex side of the house is enclosed within the volume of the building. From this position both the sliding glass doors behind and a continuous parapet above move away from the eye, creating an unobstructed panorama of the distant range. In this way the form doesn’t frame or confine the landscape but instead opens the building to it.

The exterior convex wall is made from uniformly wheat-coloured Panelrib and the concave is lined with sheets of fibrous cement. Surface ornament and material expression is suppressed, deferring to the legibility of the overall form. Notably, the form is read independent of the utilitarian steel structure that divides the dwelling into eight segments. The one-room-deep plan is extruded from a triangular setout with two radii and capped by a simple skillion roof. The kitchen, living space and office segments are on one side of the deck, with the more private bedroom and bathroom on the other. A fall in the landscape provides a receptive space for an artist’s studio beneath the office and living segments.

The varying levels of enclosure in the house are marked by a graphic application of different flooring surfaces, which are read against the complete geometry of the plan. Traces of the shifting patterns of everyday life on the property are evident in the entry-point scattering of discarded rural implements, boots and the apparel of the outdoor worker. Inside, paintings are stacked against walls and numerous ribbons from dressage events are laid out on a table for display. The informality of the lived spaces and the wilful simplicity and use of robust materials to line the internal segments offer layers of experience and texture that ruffle yet moderate the formalism of the figural plan.

The figure of the plan has been meticulously “figured” by the composition of a range of devices that orchestrate spatial experiences based on scenographic effect. At the same time, these formal arrangements are mediated by “game openings” that provide a space for an interplay of unpredictable, phenomenal experiences. The imaging of the horseshoe form establishes a knowledge base that contextualizes and mediates rather than determines our subsequent view, enriching the range of possible experiences and meanings afforded by the material space.

Rapid inner city growth and demographic change have given rise to intensive and prolific questioning of emerging urban frameworks and their architectural transformation. The subdivision of rural areas to accommodate population shifts and lifestyle changes warrants similar attention and inquiry. Critical architectural responses should acknowledge and build on the multiplicity of meanings and practices now attached to the ways we interpret and imagine the habitus of “country” life. The positioning of plan, form and experience in a dynamic and complex relationship with the rural landscape establishes a witty and provocative dialogue between the Watson House and the conditions of possibility surrounding contemporary re-imaging of the rural oeuvre.

LIAM YOUNG IS AN ARCHITECTURAL GRADUATE WHO TEACHES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AND THE QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY.

Project Credits

Architect NMBW Queensland office— project team Andrew Wilson, Angela Reilly. Structural engineers Jim Ward, Carolina Bartram and Scobie Alvis. Builders Joanne Vickery, Tim Askew, Steve Godstone and Andrew Wilson. Graphics Keith Hudson.