Koos de Keijzer

Image: Courtesy DKO Architecture

AAU: We understand DKO Architecture has been working on an unusual project – a master plan for a community on top of a volcano…

KdK: It’s not actually one volcano – it’s five! It’s what geologists call a ‘volcanic cluster’. We’re actually smack bang in the middle of it… Volcanoes for the local Maori people were very important. I think Auckland has 76 volcanoes and a lot of them are where Maori tribes settled. They’re elevated, they’re sheltered, the grounds are quite fertile, so they’re natural places for people to reside.

The Three Kings Master plan, with ‘koru’ landform and linkage visible in plan at bottom left and the ‘Big King’ volcanic peak visible top left.

Image: DKO Architecture

AAU: What were the key constraints that needed to be taken into consideration in the master plan?

KdK: There are probably two constraints – one is the cultural constraint. It is a fairly significant Maori place. We’ve spent a lot of time dealing with the local iwi (peoples] – we’re actually dealing with nine tribes, just trying to get our fingers on what the story of the place is. That’s actually put some restraints on curtilages – we’re keen to open up the vista of the Big King [the only surviving peak of the volcanic cluster] to Mount Eden and certainly to the south to the Three Kings Reserve. Part of our master planning approach has been to unlock connectivity, both physically and visually. The site itself has actually been used as a quarry for the last 70 years. It had very good rock in it that has been used for a lot of the buildings Auckland – really good scoria.

Probably the second biggest constraint for us has been sustainability – if you’re building in a volcanic cluster in quite a deep hole, you’ve really got to be cognizant of trying to get sunlight in, trying to get ventilation in – a lot of those constraints have really driven what the master plan looks like.

The quarry itself currently is about 40 metres deep, so it’s a 16-storey deep hole. We’re going to fill up two thirds of that, but we’re still keeping it 15-metres deep. Up against the cliff-faces we’re putting a whole series of apartment buildings that range in height from 7 to 10 storeys. We’ve got a master plan for almost 1500 apartments and there’s not one that faces south.

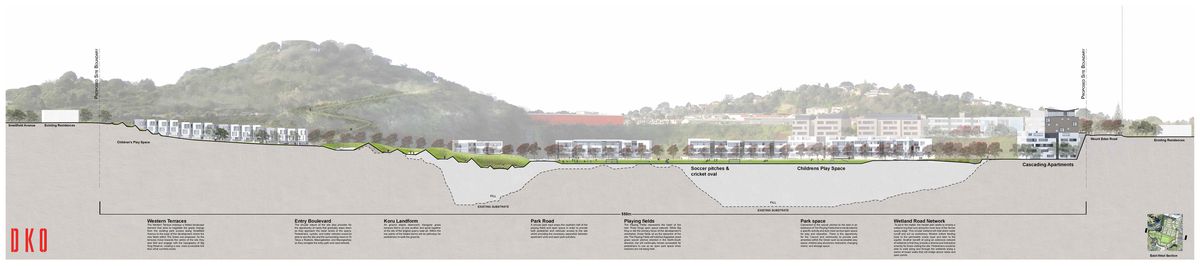

Section, with Big King visible at left and quarry infill in pale grey.

Image: DKO Architecture

AAU: Concern for ‘place’ is a common trope in architecture – integral to it, even. Strangely, though, it’s not something we often hear discussed as a key driver in master planning, perhaps because it’s seen as a more abstract concern than the functional demands of master planning allow for. How have the slightly intangible cultural and historical qualities of this place informed your master plan?

KdK: We’ve been working on this with a landscape architectural firm from San Francisco called Surfacedesign, that’s part-run by a guy called James Lord, who’s also a Kiwi but went to the US years ago. So we’ve actually let a lot of the master planning be driven by creating landforms and iwi motifs that work on the land and start to refer back to its sense of place. To try and unlock some of the cultural history of the Big King we’ve added three linkages from the east to the west, so there can be a lot more vegetation to the Big King itself. Those linkages will actually be part of what the local iwi will put in, including Maori artwork important to the nine tribes.

Like most of the new communities we work on, we’re keen to try and get a sense of history. Certainly there’s a very strong iwi history that we’ve captured well, but on the site there was also a company that made breezeblocks. There is a beautiful concrete tower there, so again we’re keen to keep bits like that, which just remind people of what was, as opposed to whitewashing everything.

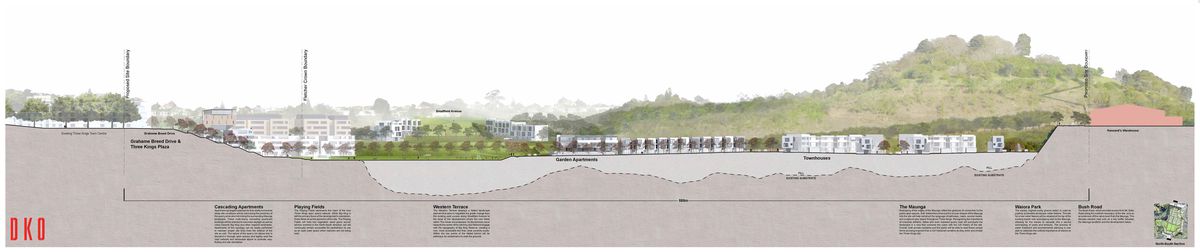

Section, with Big King visible at right and quarry infill in pale grey.

Image: DKO Architecture

AAU: As an architect who is also engaged in a lot of urban design and master planning work, what comes first for you, the street or the building?

KdK: I always reckon that you’ve got to get the big picture right – the architecture is important, but I think the public realm is much more important. I’m much more concerned with the spaces in between. It just means that you kind of set the architecture up – I hate saying this as an architect, but the architecture becomes the cream on the cake. It is important from a sense of place and character and so many things, but if you haven’t got the street right, it’s just downhill.