On approaching House with a Guest Room by Andrew Power we immediately feel the resonant tones of a meticulous architecture, three pavilions carefully arranged across a wide suburban site creating an entirely composed, modest, enigmatic setting. It reveals a classical order filtered through vernacular sensibility. We think of the ghost of Andrea Palladio’s Villa Pisani in Montagnana, transported to the great southern land, built with local know how from readily available materials. Palladio is known for his ability to combine the order and symmetry of classical structures with the everyday functional imperatives of local households. This architecture builds on such foundations.

Power’s “mature and haunting” landscape strategy accepts entropy; a mossy, coastal garden runs under and around the pavilions, beautifully challenging the villa’s strict order.

Image: Andrew Power

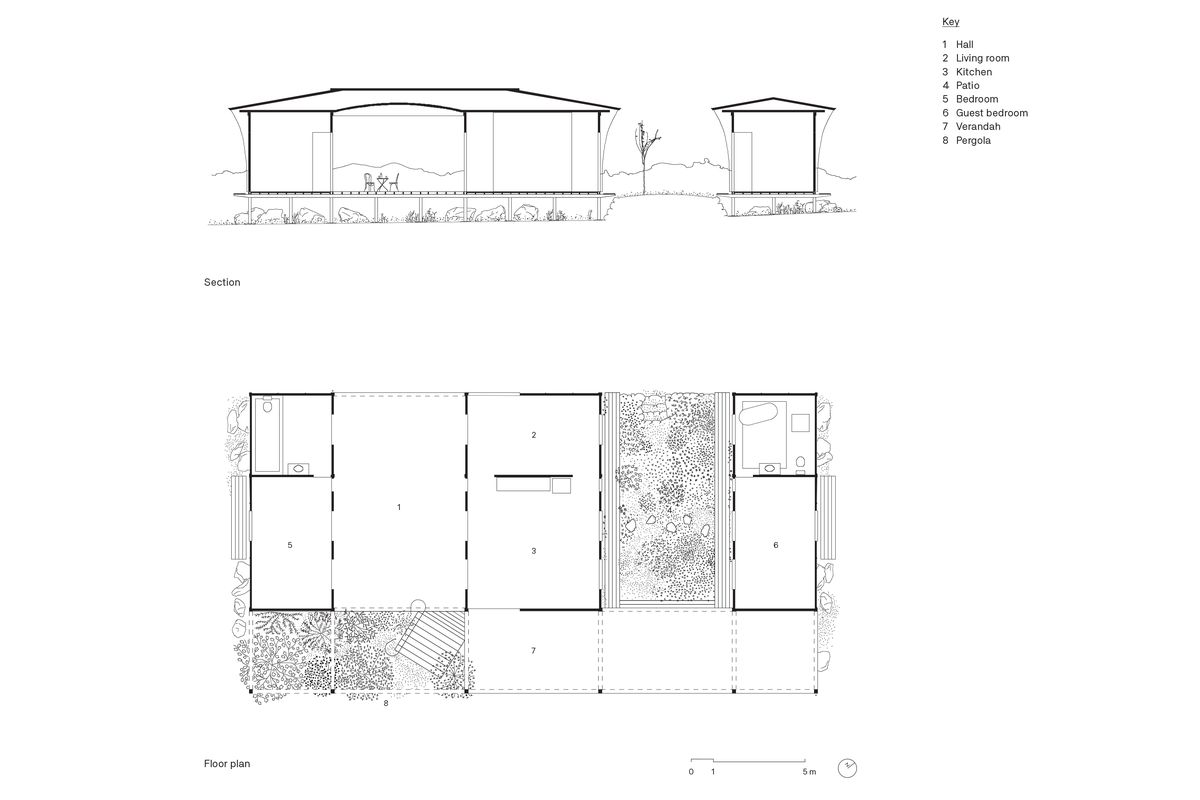

The rhythm and proportioning of the pavilions and rooms are rigorous and sophisticated. Along the northern street address in Red Head, New South Wales, there are five parts: enclosed bedroom, open hall, enclosed living rooms, courtyard and enclosed guestroom, sequenced as (A/B/B) + (B) + (A) and known as (house) + (courtyard) + (guestroom). Along the perpendicular axis there are three parts: square room, long room and verandah, sequenced as (A/B) + (A) and known as (house) + (verandah). The ratio A:B is 1.618, the golden ratio. In section the ceiling height equals A, therefore a cubic volume is formed at each corner, defining limits. Along the southern length is the (pergola) + (verandah), sequenced as (A/B) + (B/B/A) – these thin, open rooms form a slippage against the wider bulk of the house and guestroom. The house (A/B/B) is equal in length to the verandah, but as the sequential inverse (B/B/A); the house and verandah slip past one another across a central axis, creating a frustrated symmetry. Complexity is created within a defining grid, where a rich order of rooms, courtyards and gardens are arranged as a matrix of squares and golden sections, and together these compositional moves build a new and radically judicious suburban villa.

The house is strangely familiar in the sense that common things – both the house as villa and its building parts – are recast, making their perception long and laborious.1 The parts are ubiquitous and purchased locally: roof, eaves, gutters, linings, verandah, stumped floor, downpipes, terracotta gullies, bamboo skirt and various fixtures. Crucially, none is customized. Their strangeness (and thus particularity) surfaces through a combination of clear ubiquity, a quietly altered assemblage, strict adherence to the project’s classical order and a cultivated, easy wit. Collectively they constitute a seemingly ordinary house as one artfully made – you’ve seen it all before but never like this. Consistently, and at all scales, the visitor is forced to look twice, to have their base expectations met but to encounter a lingering impression of significance. We are left thinking of Frank Gehry’s early work, its coarseness and ingenious assemblage, and of his own love of hardware store solutions.

The house is positioned centrally on its wide suburban site and its portico is open to the street save for a shadecloth curtain, weighted with locally sourced metal chains.

Image: Andrew Power

A quiet confidence resides also in the project’s landscape strategy (also designed by the architect). Surrounded by low-scale cyclone fencing, the house is centrally located on the site. Both front and rear yards contain spatial figures formed by trees – the front yard is a centric ovular room and at the rear, an allée runs parallel to the house’s rear verandah. These will take decades to materialize and hold sway with the house’s scale. The oval room will be occupiable, the allée a facade to be seen through, marching downhill to the suburb. Between these grand figures is another finely scaled landscape running both under and around the villa, between its pavilions and through its ordered grid as a datum struck at 2.4 metres. Asiatic and coastal, subtropical and mossy, with a thick and varied dry-stone plinth, this fine landscape will engulf the work and challenge (or liberate) its strict order. A tragic beauty presents itself through the acceptance of entropy. These actions are conscious, mature and haunting. Power’s collection of photographs portraying domestic settings in Mackay, Queensland, during the nineteenth century and of Robert Smithson’s Hotel Palenque resonate deeply as contexts to his strategy. We imagine the fertile ruins of Ancient Rome but emerge from these thoughts in a coastal suburb. In The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa: Palladio and Le Corbusier compared, Colin Rowe notes: “Perhaps these were the dreams of Virgil. Freely interpreted, they have gathered round themselves, in the course of time, all those ideals of Roman virtue, excellence, Imperial splendour and decay, which make up the imaginative reconstruction of the ancient world.”2

The shower pipes take the form of a wishbone, adhering to a bilateral symmetry, while the marble unfolds geometrically across the walls and floor.

Image: Andrew Power

So here we stand in a new house, so thoughtfully commonplace it makes us shiver. The floor, set at eye height, creates the piano nobile related immediately to human dimension, a platform accessed from the rear via timber stairs where a single, perfectly bent handrail forms a sinuous figure against the strict orthogonal grid. This sensuous line leads the hand into the open portico, where we arrive below a shimmering pink vaulted ceiling, where chairs arranged from prior conversation wait for new participants and a shadecloth curtain – hanging just so, hemmed with locally sourced metal chain for weight – veils the merciless street. Off the portico – a roofed courtyard – we can ramble into other rooms: a bedroom and ensuite to one side, a drawing room and kitchen/dining the other, so carefully careless3 that the ramble starts to feel natural (despite an indifference to solar orientation, something we hope for in time). Inside the kitchen hub we notice the entire place unfold as a series of scenographic vignettes – registering and amplifying the smallest of movements – through rooms, across moss gardens to a guestroom where clothes hang delicately, precariously, in a room beautifully arranged with spartan adornment and phenomenal material moments. Within, an aluminium-lined timber door holds light in its surface, leads to the adjoining ensuite and conjures the ghost of Adolf Loos speaking into the void, whispering “ornament is crime” as an evocation to the finding of beauty in direct pragmatism and natural material quality. In House with a Guest Room we are close to the ordinary suburban street, furnished with a garden shed, close to public walkways leading to the beach and surrounded by gardens and fences, yet we are totally transported to a place where we muse and rummage, think and sense, all the while feeling somehow comfortable and at home.

1. Viktor Shklovsky, Theory of Prose (Illinois: Dalkey Archive Press, 1991).

2. Colin Rowe, The Architectural Review , vol 101 issue 603, 1 March, 1947, 101–104.

3. Robert Maxwell, Sweet Disorder and the Carefully Careless: Theory and Criticism in Architecture (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993).

Credits

- Project

- House with a Guest Room

- Architect

-

Andrew Power

- Consultants

-

Builder

Gavin Limpic Building

Engineer Leunam Civil Structural and Hydraulic Engineers

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2017

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 19 Jun 2018

Words:

Stephen Neille,

Simon Pendal

Images:

Andrew Power

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2018