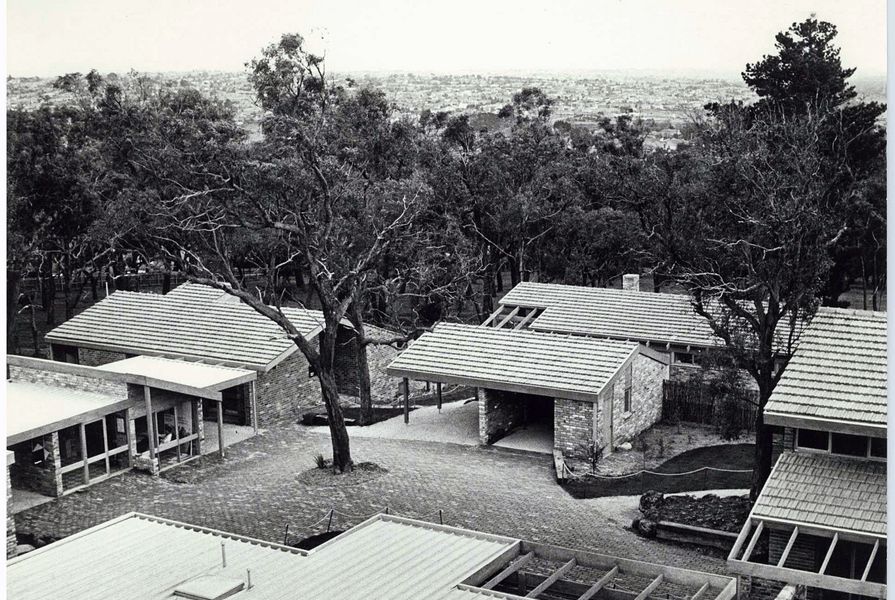

The houses sit low: pale brick, terracotta and greyed timbers seamless extensions of their brick and native planting landscapes. Surrounded on all sides by rows of suburbia, the clustered dwellings – and the stands of eucalypt that congregate around their shared central parkland – seem curiously out of place, as if they are intrusions from some alternate reality, which, in a way, they are.

They seem to come from a universe where other policies were pursued, where values were subtly different. The buildings - four groups of five peripherally connected dwellings - are the Winter Park development in Doncaster. The site is perhaps the best built example of the philosophies of Merchant Builders and its driving architect, Graeme Gunn - the sensitive and sensible use of architectural space joined to shared gardens and screening landscapes. The buildings’ muted forms and integration into Ellis Stones’ landscape planting stand in stark contrast to the jostling forms of the surrounding suburban fabric. For a few brief years in the 1970s, this knot of well-designed, sustainable, community focused dwellings offered the most convincing solution to the relentless march of suburbia.

Alternative models to traditional suburban development, in terms of both design and the industrialized delivery of the product, have always existed. Robin Boyd’s work with The Age Small Homes Service, and his partial success with clustered housing in the Appletree Hill project, spring instantly to mind. A number of architects in other Australian cities, such as the project builders Pettit and Sevitt with architect Ken Woolley in Sydney, pushed ahead on alternatives to relentless suburbia. The primary vehicle for the restitution of this fabric in Victoria was the work of the Melbourne-based Merchant Builders - driven almost entirely, in their earliest years, by the design sensibility and taste of Graeme Gunn. Beginning with his early work for Merchant Builders, continuing in his advocacy for contributory and humane architecture as Foundation Dean of the Faculty of Architecture and Building at RMIT, and in his present role as principal architect to VicUrban, Graeme Gunn is an enduring and inspirational advocate for architecture’s contributory engagement to our housing and urban environments.

Recent strategic plans for Australia’s major cities attempt to move away from greenfield development as the principal means of delivering new housing for metropolitan residents. Most state governments have targeted 50 percent or more of new housing development to be built within established residential areas - principally, the inner and middle ring suburbs. Based on redevelopment patterns to date, the challenge of meeting these targets in a manner that would provide for contemporary households and improve social and environmental sustainability seems remote. The general housing industry is characterized by craft-oriented, innovation-averse, inexpensive methods of delivery with little or no design input. General housing provision is increasingly mismatched to our complex household structures and is increasingly unaffordable to its traditional first home buyer market unless they choose to live in unserviced peripheral locations. The production of housing is a complex field that requires creative solutions - a challenge that presupposes a greater level of architectural participation. However, what should the nature of this participation be? It is difficult to find architecturally led advocacy around an informed response to the issues of appropriate housing and housing affordability. Graeme Gunn has provided this type of advocacy for more than forty years.

Graeme is remarkable for the quiet optimism he brings to the challenges of housing and his preparedness to lead with models that were innovative and risky. This also says something about the times and the importance of David Yencken’s enlightened vision of appropriate development. Gunn’s work already demonstrated a fascination with innovative typology in the Molesworth Street townhouses of 1968, which also prefigure the cluster typology of later projects. The staggered concrete blockwork structures - executed in Gunn’s characteristic palette of muted greys - gather around a shared driveway over a steep site overlooking the Yarra River. The variegated forms reflect the terrace typology, but the mass is dispersed, broken into something closer to a small village cluster, tied together with consistent landscaping and planted screening. These concepts would be further developed and finessed in Gunn’s work, alongside architects including Daryl Jackson on the Elliston development.

At Winter Park we see the fullest articulation of the cluster approach. The four-staged arrangements of the development gather around paved parking courts, the interior of the site given over to a stand of eucalypt parkland. The density of the project is comparable to the surrounding suburban fabric - this is not a vehicle for intensification, nor was it intended to be. Instead, it illustrated the benefits of careful design extended into a consideration of the importance of landscape and open space and, ultimately, the presence and feel of a place. Winter Park is one of the best examples of the way in which Gunn and Merchant Builders “educated and articulated new ideas to the public”.1 As such it stands in stark contrast to the marketing of much of our contemporary suburban project housing, which is sold to its consumers in an identical manner to the “upsizing” of junk food in fast food outlets.

There is a dull irony in the fact that Winter Park - an almost archetypal “cluster” development - predated the advent of cluster housing as a policy. Instead, it was executed under the auspice of the earlier Strata Titles Act 1967, where the shared spaces were administered under a body corporate; the cluster dwellings joined with a connective tissue of pergolas and carports were required to qualify it as such. The need for a dedicated policy on cluster developments was clear, and led to the initial formation of the Victorian Cluster Code Committee in 1971, headed by David Yencken with substantial involvement from Graeme Gunn.

The work undertaken alongside Yencken, which led directly to the creation of the Cluster Titles Act 1974, is representative of Graeme’s wider preoccupation with housing and urban issues. His involvement in these issues was not restricted to dwelling design or the promotion of alternative housing models. As head of the RAIA’s Public Services Committee he presided over a period of time in which the future of Australian cities, their character, scale and overall feel, hung decidedly in the balance. Debate centred on issues of restoration, recycling and conservation of the urban building fabric, a reaction to the wholesale slaughter visited on extant Victorian architecture within the inner city at that time. Contemporary literature is replete with invective levelled against the Housing Commission of Victoria’s extensive slum clearance and high-rise tower building approaches, excesses that the committee was instrumental in halting.

The built environment cannot be protected solely by legislation and it was Gunn’s design ability applied to the new multi-unit legislation of the time that led to the very rich outcomes evident at Winter Park and Molesworth Street. Today the Strata Titles Act presents us with significant challenges around the redevelopment of property, particularly multistorey strata-titled buildings, which, due to their number of separate titles, present significant challenges for sustainable retro-fitting. Even during the seventies concerns were being voiced about the wave of multi-unit development transforming the city and suburbs. Writing in The Age on 18 May 1970, Graham Whitford, then director of the RAIA Victorian Chapter Housing Service, rails against the poor state of apartment development before praising the fine alternative to this presented at Molesworth Street. ” … more money can be made by cramming the maximum amount of cream brick accommodation on to a site and then dressing it up with arches, multi-painted windows, a scattering of pebbles surrounding plastic like plants, and an inappropriately dignified name.” By contrast, the joint bronze medal winner “Merchant Builders have chosen to reject this approach in favour of lower density family accommodation oriented towards the needs of the future inhabitants rather than short-term profit for their own pockets.” Similar concerns would lead to the publication of A mansion or no house in 1976.2 The authors, concerned about the affordability of housing, argued that increased urban densities appropriately designed would lead to lower prices for housing, a proposition very familiar to contemporary readers but one that unfortunately has not come to fruition. These approaches are also articulated through Graeme’s work with the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) - which furthered approaches of clustered housing to augment and re-enforce community and sense of place.

Graeme’s desire to continually promote architecture’s contributory role was also pursued through his significant contribution as an educator and an instigator of student-centred learning. As Head of the Department of Architecture and Building (1972-1977) and then as Foundation Dean of the new Faculty of Architecture and Building at RMIT University (1977-1982), Graeme promoted the studio model of teaching in which invited practitioners delivered much of the design education. He also established the new Department of Landscape Architecture within the faculty. The faculty under Graeme’s leadership became a place that, as Peter Corrigan observes, “still operates within a framework of inclusive humanism and genuine enquiry”. Graeme’s emphasis on the importance of the practitioner teacher was extremely significant in forging RMIT’s national profile as a design school. For students at RMIT, Graeme brought a unique authority to his message of a contributory architecture through the example of his own architectural mastery. This he demonstrated in an outstanding resume of buildings including the Nicholson House, the Molesworth Street townhouses, the suite of houses for Winter Park, the spectacular Plumbers and Gasfitters Union Building, Prahran Market, Melbourne City Baths and recent projects such as his deftly handled Carlton Courtyard House.

Graeme’s most recent public role has been as principal architect with VicUrban, and prior to that as principal design advisor to the Docklands Authority. In his work with VicUrban he has not only provided strategic design guidance, mentoring junior colleagues, but also quietly promoted the importance of the built exemplar. As he did with Merchant Builders many years before, at VicUrban Graeme continues to advocate for strategies that will allow experimental projects to be built that translate and test ideas, as distinct from verbalizing the potential of good and more appropriate urban design and architecture.

Graeme has made an exemplary contribution to architecture in a career spanning more than five decades, one distinguished by three distinct forms of engagement. As innovative architect, inspired and influential educator and advocate for architecture’s potential to improve our social condition, he has made an unparalleled contribution. He pursued his ambition to demonstrate innovative architecture while at the same time harnessing his creativity to improve the quality of how we live and to project architecture to a broader group of people than would normally be able to afford it.

1. Anne Gartner, Merchant Builders from reform to receivership Monash University; Dept. of History. Thesis.

2. John Paterson, David Yencken, Graeme Gunn, A Mansion or No House: a report for UDIA on consequences of planning standards and their impact on land and housing, 1976.

Source

People

Published online: 1 Mar 2011

Words:

Shane Murray,

Tom Morgan

Images:

Aaron Tester,

Aaron Tester.,

David Simmonds,

Graeme Gunn,

Ian MacKenzie,

Kurt Veld

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2011