It is not uncommon for a nation to express its identity through architectural forms at a global event like the World Expo or Olympic Games. Most often this happens via an image. This might be a vernacular or technological motif, or simply an expression of a nation’s enlightenment through the patronage of advanced architecture. The ready-made archi-postcards from these images reflect to others what a nation is, or rather, how it expects others to identify it. These identity games can at times become as tiresome as languishing in a tourist queue.

I considered such questions while in the crowds for the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai – a zoo of national identity architecture; a super-compressed precinct of pop embassies. This was a big zoo, with 250 nations and international organizations present in a series of wildly varied pavilions, ranging from gargantuan landmarks to modest off-the-shelf sheds. I wondered: to what extent could these architectural pavilions be asked to represent their nation, and to what extent were they metaphors for their country?

Organizers of World Expo 2010 planned for seventy million visitors, with a daily average of three hundred thousand people. That number was often exceeded, with the record day attendance figure reaching 1.03 million people. At certain moments, it is estimated there were two hundred thousand people in a queue. It was not uncommon for visitors to wait for five hours and to spend less than an hour inside a pavilion.

Snaking outside buildings of amazing architectural complexity were ribbons of shelters – generic steel frames covered in canvas. This was the spatial experience which, for many, dominated during their time at the Expo. Waiting to enter these metaphorical nations, I was reminded of a bleak moment of Australia’s recent past, when in 2001 then-prime minister John Howard said, “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.”

This phrase was spoken amid a noisy discourse around the term “queue jumper.” Unhindered by facts, “queue jumper” became a term used to describe asylum seekers, and quickly gained currency in mainstream media and in the Australian parliament. This thought jarred as I skipped the Japanese pavilion queue and wandered into the North Korean pavilion, unimpeded by a waiting line. I wondered, could it be that the defining way we convey an identity is in the way we approach those outside wishing to enter, or indeed those inside and wishing to leave?

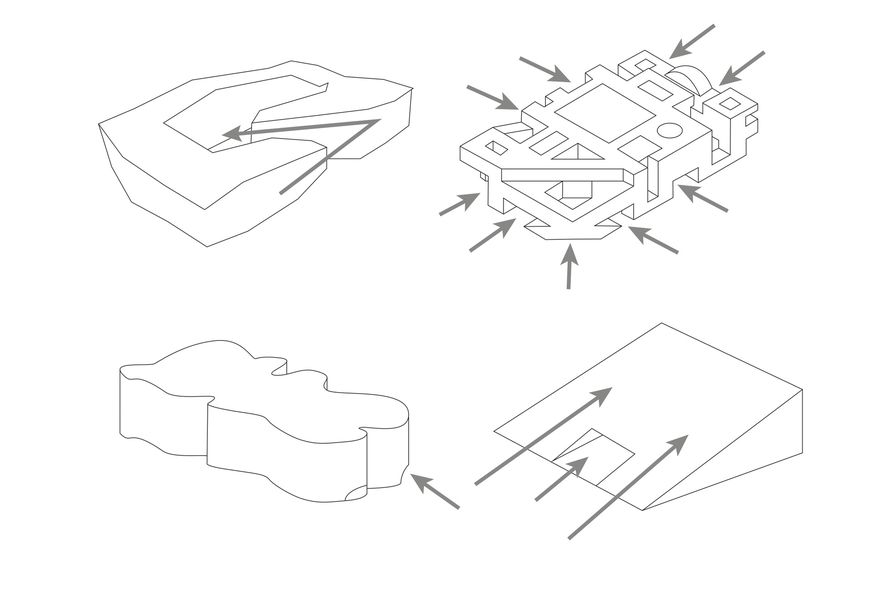

Differences between pavilions were evident across the 5.28-square-kilometre site. The Mexican pavilion was defined by a slope that climbed to form a landscape roof. One could descend below the slope to enter the exhibition interior – or instead, one could simply climb the Mexican hill unhindered and sit on a raised public lawn under some artificial trees with fluorescent foliage. The C-shaped plan of the Canadian pavilion meant that prior to accessing the interior, one entered a contained courtyard designed for performances that offered a panorama of wooden surfaces. The Republic of Korea pavilion designed by Mass Studies dealt with the visual image of letter forms of the Korean alphabet both at a giant scale (as building) and as perforated wallpaper. The external space created by the large intersecting characters was a huge public environment – at once undercroft, courtyard and performance venue. Waiting under the big characters was also like being inside them, while at the close range of the queue, the skin offered its text to be read. A highlight of the expo, this building left a memorable image both as super-graphic and fine skin, while managing both huge populations and the individual in the queue.

The enigmatic Australian pavilion was in some ways the opposite to this. The large red oxide monolith was no doubt identified by some tourists as Uluru (or at least as a big red desert landform). It was not the only pavilion to engage abstractions of nature – the Finnish pavilion folded into a Nordic, glacial white courtyard. What was most striking in the Australian pavilion was the stark division between inside and outside; the chasm between the monumental steel facade and the commercially fitted interior. While a number of pavilions treated their interior as a folding in of the exterior skin, the Australian pavilion had an unambiguous door in and out. In the evening, when performers set up next to the pavilion with the red wall as a backdrop, they were unambiguously outside, without even a verandah to cover them.

It might seem odd to talk about these architectural experiments through the prosaic act of lining up, but it does trigger a question that widens into reflection on how we identify ourselves. How open are we? How does one experience the nation from the view in the queue, and might this affect the view of our cities, suburbs and most well-known architectural exports? While it is overstating things to see buildings as a metaphor for a nation, an Expo pavilion would have been for many Chinese visitors all they experience of a country. We may wish the interiors provided the memorable moments, but this is often not the case. Two years on from the 2010 expo, the issues around the idea of an open society and its architectural equivalent are still with us. What the pavilions offered in terms of the experience of outsiders in the queue was perhaps more revealing than anyone could have anticipated.

From a dossier in the July/August 2012 edition of Architecture Australia, on “Australian Style.”