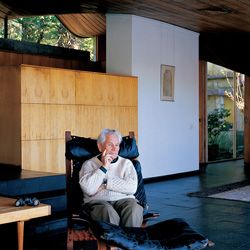

Hugh Buhrich at home in the house he designed and built between 1968 and 1972, the “most intensely personal” of his projects.

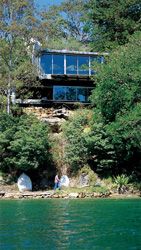

The water edge facade. The house snuggles into the bush on the northern tip of Sugarloaf Point, Castlecrag.

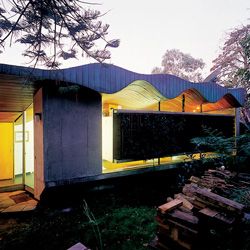

Looking along the bush facade, with undulating roof and “floating” concrete wall panel.

Buhrich describes the house in terms of its relation to its dramatic waterfront bush site.

The main living area.

The floating concrete panel, with dining table in front.

Looking down the length of the house, the living area is to the left and kitchen to the right.

The kitchen, with its rising curving ceiling.

Concrete detail.

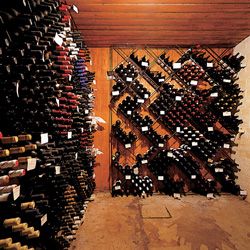

The wine cellar hidden beneath a closet.

Looking along the hall towards the bedroom.

The lipstick red fibreglass bathroom.

Reason and emotion. The sinusoidal ceiling/roof and hovering concrete panel tucked into the bush.

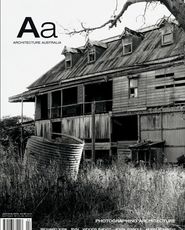

As Hugh Buhrich tells it, his life has been more found than made, a crooked chain of accident and happenstance connecting Hamburg, 25 April 1911 to this sunny Castlecrag cliff edge, 93 years on. Buhrich’s house, described by Peter Myers as “the finest modern house in Australia”, has something of the same incidental quality, an extraordinary, almost casual beauty that weighs the synthetic against the organic, balancing abstract cool with high-cal expressionism, the deliberate with the chanced upon.

As a teenager Buhrich loved modern design but, being “hung up” on Freud, would have pursued medicine, not architecture – except that medicine required Latin. As a Bauhaus fan, he would have enrolled there, except that its non-university status would have rendered his scholarship invalid; and since the same scholarship required him to leave home, he enrolled at a “not very good” architecture school in Munich, because of its proximity to Hamburg. Forcibly ejected by the Nazis in retaliation for student political activity, Buhrich moved to Berlin, where he worked with Hans Poelzig (“like a really first class Leslie Wilkinson”) and met Eva, a fellow student whom he would later marry; then to Zurich, where he studied under the domineering Otto Salvisberg and could barely afford to eat; finally completing his degree at a “really shocking university” in the German Free State of Danzig, now Gedansk, where, ironically, he was one of several students subsidized by the Nazis in order to preserve German cultural dominance.

Eva, fleeing Germany, went to Holland, where Hugh could live but not work, then to London. There Hugh found a cheap flat in Hampstead but was dismayed also to find that, despite eight years of school English, it took him twenty-five minutes to ask for a packet of Players cigarettes. From London, with help from the Quakers, the Jewish Institute and the RIBA librarian, they might have emigrated to America, only it was too competitive, or South Africa which, demanding a $200 landing fee, was too expensive.

So Australia became the lucky recipient of Buhrich’s undersung genius.

Even then, the path became only gradually smoother: in 1939 the University of Sydney’s Professor A. S. Hook helped the new arrivals secure a (shared) architectural job in Canberra, but when war broke out, the Miss Hall who had vacated the job returned, and the Buhrichs were sent packing. Eva quickly embarked on a writing and editing career, later publishing Furniture Trends and Building Ideas for CSR through the1960s and 70s. But Hugh joined the army, resuming practice only after the war.

Even then, remaining unregistered in New South Wales until the early 1960s, he restricted himself mainly to furniture and interiors. “Every time I designed a building,” he says, “I would get a ‘please explain’ letter from the registrar …” ›› Nevertheless, some twenty-odd of Buhrich’s buildings were built during those years, most of them houses, many now demolished. His own house, largely self-built between 1968 and 1972, is comparatively late in the oeuvre; perhaps the most accomplished of his works, probably the most vivid and “certainly,” agrees Buhrich, “the most intensely personal”. Described by French critic Françoise Fromonot as “a truly radical building”, it has become a classic cult object, more celebrated abroad than at home. After thirty years inhabiting it, Buhrich can think of nothing he would change “except maybe some light points and switches”. Not bad, as client recommendations go.

Snuggled into its rocky bush setting on Sugarloaf Point’s northerly tip, down the far, secret end of Edinburgh Road, the house is about as remote as you can get in a global city. It is a remarkable house on a remarkable site, and much of Buhrich’s narrative is couched in terms of simple, practical response to the parameters of place and praxis.

On the house’s most distinctive moment, for example, its sinusoidal south-facing roof-ceiling, the Buhrich version goes like this. Site-response was a given: “the Greeks,” he reflects, “placed their temples on top of hills to stand out, but if you build a house it has to accommodate the landscape.” Buhrich had always wanted to live by the water, and wanted his house on one level, facing it, but also a sense of “going downhill” towards – hence the sloping ceiling, up from the legal minimum at the northern edge.

At the same time, the otherwise bush-facing kitchen needed to step up for views over the living space, but the Act allowed no more than twenty-five per cent of the ceiling area to drop below eight feet. So it was “just a practical response: I decided to push the ceiling up between the trusses” – a solution with the added virtue of admitting extra light. The opposing curve of the copper-clad roof, explains Buhrich with equal simplicity, arose from a need to accommodate the depth of trusses, spanning as they do the full eight-metre width of the house. And then there’s the bathroom, that bathroom: a seamless, detail-less, breathtaking lipstick red, which Buhrich accounts for as a simple development of three facts – that he’d already built a fibreglass yacht, he’d never liked fussy bathrooms and he did like occasional strong colours. Simple, really.

But of course there’s more to it than that. Site-response is all very well, and this is a site of no small presence. But every nuts-and-berries house in town was doing the same theoretical thing, and not one of them looks like this. It’s not just the roof. There’s also the curious angularity of the plan, with its casual commingling of the regular and irregular geometries; the craggy yet sprightly elevations, stamped with great irregular concrete slabs that float like icebergs on the cliff edge; the rough-hewn sandstone fireplace wall; the terrifying edges of deck and stair. And the bathroom.

The essence, in many ways, is in the section: snuggled into bush and crag it may be, but the only point at which house and planet actually interpenetrate is the wine cellar, a secret cavern hidden beneath a closet. Otherwise, the heavy in situ concrete structure floats ethereal, as effortless as the “floating” concrete wall panel under the undulating ceiling, lending to the whole a submarine surreality, a lightness of being that resonates endlessly with the watery view.

It’s eclectic, but consistent in its eclecticism, each part bringing not just opposing sine curves but two opposing world views into head-on collision: simple planar rationalism meets organic neo-expressionism. “Yes, I suppose you could say that,” reflects Buhrich, as though it’s the first time the thought has occurred to him but advancing no further explanation as to his intellectual sources. Commentators have suggested influence from the Ronchamp and the Maison de Verre, but the house sits more easily between two characteristically German streams of the high Modern: Miesian (quasi-)rationalism and the techno-organic tradition of Scharoun and Behnisch, with their characteristic amalgam of minimalism and expression; reason, if you like, and emotion. The site may be absolutely Sydney, and the house may be a wholehearted response to it, but its guiding spirit, for my money, is a thoroughgoing, international, surreal-edged, Miroesque abstract expressionism.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jul 2004

Words:

Elizabeth Farrelly

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2004