Looking back over recent history, we might ask the question: How soon will we forget the Hills Hoist? More importantly, perhaps, will we recall the Victorian Football League shorts drying beneath humming power lines? Is there a historical shared experience that can be called Victorian, and how does this, like a twenty-cent bag of mixed lollies, inform our imagination and expectation of a city? Can we still speak of a Victorian architecture without the risk of thinking of a pedestrian plaza?

In his essay Against the Mainstream, Conrad Hamann suggests that following the initial enthusiastic architectural reform of Federation, significant regional differences developed in architecture across Australia. Victorian architecture remained poignantly tied to this wave through the persistent questioning of an authentically Australian architecture, sought through an architecture that was a synthesis of urban, suburban and country. An inconsistent lineage from the 1890s to the mid 1980s (when Hamann’s essay appeared) characterizes the emergence of this architecture of plurality, denoted by an inclusiveness and literacy of styles. The assertiveness of a regional architecture remains in the current bow wave; however, its concerns — or rather, the way it imagines its plural identity — have conceptually altered.

Thus, an invitation to write on style, let alone to distinguish what makes the current crop of architecture regionally significant, is an offer to pay up front for the indulgence: style is a pleasurable invention, but it ultimately makes one either want to reach for one’s revolver or chequebook.

It might be argued that positing the idea of a Victorian architecture could once again refocus the gaze of the various international magazines that have trained their lens onto the antipodes, and along whose channels Australia’s inconclusive inroads into Venice have been furrowed. How Australian is it? Leon van Schaik has already identified the difficulty of an “Australian architecture” in his essay headed by this same question. This is Australia, and that’s OK. She’ll be right, mate.

Van Schaik’s question draws out the tightening of hands around Hamann’s proverbial loose end during the procurement and construction of Edmond and Corrigan’s Building 8. Evidentially, Jennifer Hocking has remarked on the number of architects that had previously worked for Edmond and Corrigan. But a more pertinent observation on Victoria would have been that Melbourne still maintains its 1966 floral clock — a return of temporal fauna to Melbourne after the 1888 version for the Centennial International Exhibition.

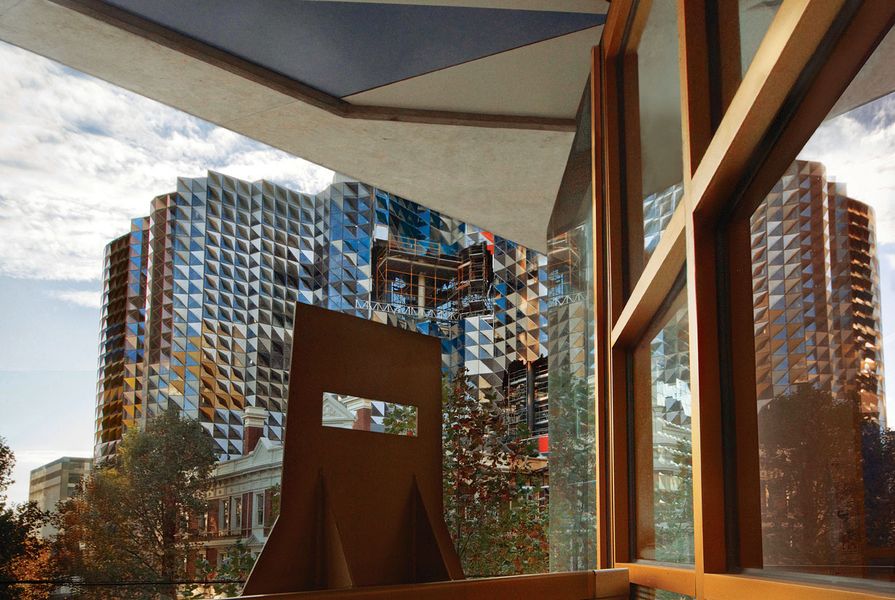

Empirical evidence of the past twenty years of Victorian architecture continues to be found loitering about Swanston Street, between Lonsdale and Franklin Streets and, in particular, in the askew face-off between Building 8 and Lyons’s Swanston Academic Building (SAB) that is currently nearing completion. Both have a stake in a quest to understand plural Australian architecture through a plurality of architectural tropes, styles and references. But, post-Building 8 architecture in general has taken on similarities more akin to suprematism in its attempt to encapsulate the complexities of immediate and broader contexts through a nature and through a geometry that causes architecture to revert to a subordinate role.

Ashton Raggatt McDougall’s Storey Hall, adjacent to Building 8, is an instance of what can be realized when architecture is conceived on a temporal and even footing with physics, chemistry, painting and music, practices which are grounded in the comprehension of an immutable unknown. Storey Hall is an architecture that shares with these practices their lucid intervals of thought and that fosters, without appeal to some lost architectural Eden, a role for architecture. Establishing this role is the single greatest challenge faced by the profession, a claim that offers a retort to the troubling, but not unexpected attention that contemporary architectural discourse has paid to our environmental anxiety. Hence SAB, seen against John Wyndham’s Kraken Wake, having fallen unknown from the heavens and risen from the ocean, could conceivably melt the polar ice caps and flood the city. And thus maybe “Corro” has had the last laugh as Building 8, seen by ARM’s Howard Raggatt during the design of Storey Hall as a phantom ocean liner, draws anchor and like an architectural ark makes for the local Ararat.

Yet Building 8 draws on the common too, but does so in a more knowing way. This is, ironically, problematic in our “information age,” where value and understanding are subsumed by sheer mass. Nevertheless, its classical composition is distinctly Victorian. In roughly gathering up its urban locale, it also pulls in the suburbs and country. Its loose precision of expression gathers up those things that are Victorian and produces an assemblage that is technically true, but which is also a time capsule: the fading relevance perhaps of a building as a city. Like picking up an early 80s copy of Transition magazine.

Lyons, however, deals in a primitive architecture, but not in a pejorative or Laugier-like Parthenon, cubbyhouse sense. It is not primitive in the sense of being an idealized colonial “nature” or “native,” but instead delves back into something fundamental. It speaks to intrinsic reaction to form rather than extrinsic reading. Unusually, it offers itself whole, whether you grew up across the road or not. Lyons offers gnashing teeth streaked with lipstick, articulated by the suggestion of some fundamental order (openings that at once appear lewd and threatening mark the extent of the building’s arboreal circulation). They woo us with a false-nail exterior, bristling like a beckoning hand, the pungent smell of the newly attached nails sharpening every gesture. Thus a city in a building is turned outward: a heaving, bulging architecture is distended and shaped by the enormity of an idea, the city, that which is found couched in Hamann’s pluralities. A city that is at once urban, suburban and country. This is to suggest that the city is still a rogue idea; an idea without assurances.

On one side of the street we see Hunters in the Snow by Pieter Bruegel the Elder: a work full of allegory, full of intention. On the other side, we come up against the new deal — a square building in a larger, square city. What might come to rest at the feet of a Victorian architecture is a hope for the city.

Swanston Academic Building is reviewed in Architecture Australia Sep/Oct 2012 edition.

From a dossier in the July/August 2012 edition of Architecture Australia, on “Australian Style.”

Source

Discussion

Published online: 5 Sep 2012

Words:

Michael Spooner,

Peter Knight

Images:

Katherine Brice

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2012