As I approached the entrance of Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), I was struck immediately with thoughts about the relationships between Australian art institutions and First Nations peoples and their cultures: broken and exploitative relationships governed by the colonial imperative through 230 years of theft, dispossession and silence.

Walking through Sir Roy Grounds’ building towards the garden, a monolithic form, in both stature and structure, immediately confronted my senses. The form appears as an imposing eucalypt, burnt by the wrath of fire – yet resilient and strong to its core, its black and charred skin protecting it from the fury – healing and regenerating from within.

The 2019 NGV Architecture Commission, In Absence, is a collaboration between Kokatha and Nukunu artist Yhonnie Scarce and Melbourne-based architecture studio Edition Office. Situated directly outside the heavily walled NGV building, In Absence beckons for the truth of a history that has long been void of proper truth-telling.

The two monolithic chambers are exactly mirrored, symmetrical in shape and proportion.

Image: Benjamin Hosking

The axial relationship between the commission and the NGV building forces a dialogue between the tower’s physical form and the ideas that manifest within. Eyeballing the NGV, a celebrated icon of the Western canon of architecture, the structure breathes life and connects to earth, sky, Birrarung and Country. This is no ordinary museum exhibit encased within a glass box or accumulating dust in a distant archive.

The nine-metre-high tower is clad in stained Tasmanian hardwood, coarse in texture and rich in the scent of ash and eucalypt. Edition Office director Aaron Roberts states, “The building asserts a physical presence and a physical manifestation of the ongoing colonial project. In a very clear way, it talks about the absence of truth.” The exterior acts as a shield – sheer, strong and resistant – protecting and nurturing its womb from perpetual settler-colonial violence.

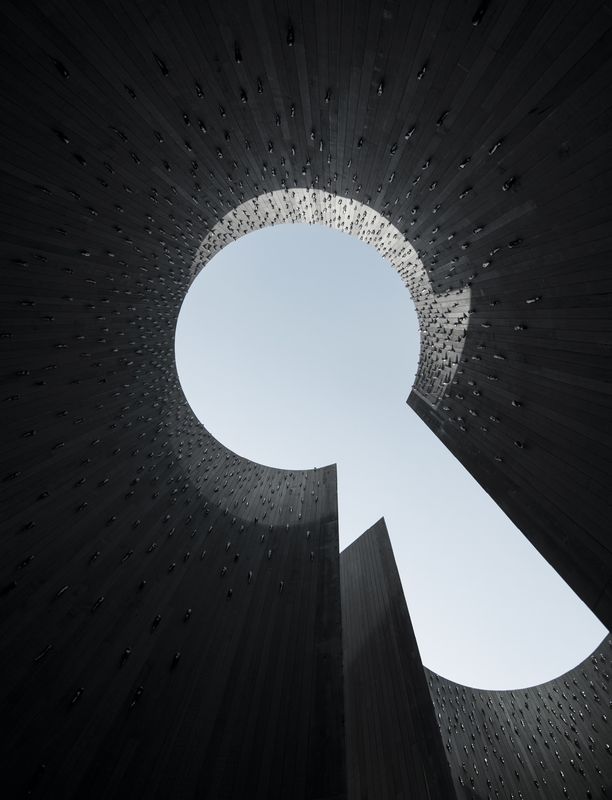

Set directly on axis, a narrow vertical aperture bisects the two chambers, leaving a void in its wake – addressing the conditioning of terra nullius and the consequential psyche devoid of truth-telling. The chambers are exactly mirrored, symmetrical in shape and proportion; a platform that removes power imbalances and opens up conversation and dialogue. Inside the space, one cannot be neutral, unaffected nor an outsider looking in. In Scarce’s words, “C’mon then. The door’s open; however, there comes responsibility walking through.”

Inside, two curved chambers contain 1,600 black hand-blown glass yams, which seep out of the cracks in the chambers’ walls. These yams resonate with history, bear memory and reflect and reclaim agricultural practice that reaches back beyond two thousand generations. “Given life through breath,” Scarce explains, “the glass is fragile to some extent, but these yams reference the resilience of Aboriginal people. They have this strength about them. They take on their own personality, their own existence.”

From within the chambers, the city and its white noise disappears. Mind, body and spirit connect to the vast sky and the sun as it passes overhead.

Image: Benjamin Hosking

The diameter of the chambers and their circular form abstractly reference in plan and in scale Aboriginal peoples’ stone-based permanent dwellings. The spatial intimacy and transparency is a response to the persistent absence of truth, whereby colonial and, indeed, contemporary Australia has sought to mask any trace of evidence that might dispute the myth of Aboriginal people as nothing more than nomadic hunter-gatherers.

From within, the city and its white noise disappears. Mind, body and spirit connect to the vast sky and the sun as it passes overhead. Each noise that is projected into the space comes with vitality and responsibility as your voice reflects off the walls and rebounds back to you. This deeply spiritual and acoustic reverence reveals timeless cultural protocols of deep listening, reciprocity and reflection. This is where the beacon of truth-telling lies.

Foundational to the project is its public program. Edition Office director Kim Bridgland shares, “Fundamentally, what this building is doing is being a memory keeper, as well as a memory sharer. It’s an enabling platform for stories from Indigenous community to be heard, and to be able to have that conversation in the way that they want to have that conversation.” Meaningful relationships that centre Aboriginal people and their voices in the project are vital.

In Absence reaches far beyond a Western methodological viewpoint of an object within a landscape. The incorporation of Aboriginal sovereign foods and materiality acknowledges the past, present and future, dismissing a history that has been falsified while urging a rapprochement with Aboriginal people and the land itself. The basalt rock – a material used for stone-making for thousands of years – forms pathways through space. Kangaroo and wallaby grass wrap around the tower, spread among three species of planted yams. When the pavilion is dismantled, a mature native bed will lay bare, revealing yams ready for harvest and kangaroo and wallaby grass ready to ground seeds into flour. In contrast to decommissioning and destruction, this work will renew, restore and regenerate.

In Absence is a stark reminder of the great white lie of terra nullius. Aboriginal people exercised their sovereignty and custodianship of land and waters while maintaining law, creating kinship systems, planting and harvesting grain, forming settlements and caring for Country. This land was not free for the taking.

How can architecture reconcile with the brutality of an unlawful and violent colonial history in which the mortar that binds us is comforted by invisibility, absence and untruth? In Absence has the capacity to do more than become a “feel-good” decolonizing motif for the wider architecture community to revel in. This is an interrogation that should go well beyond the life of a six-month exhibition. But what comes next – an elevated platform for Aboriginal sovereign voice within the built environment, or merely a temporal thematic engagement, ultimately judged as worthy by a jury of non-Indigenous peers?

Architecture has the unparalleled potential to bring us to a place where voices rendered silent for so long can be heard, where disruptive and difficult questions can be asked, and forgotten truths can be told. Fundamentally, it’s a question of power. In Absence has illustrated the power of architecture to reveal, to resonate and to rethink.

In Absence is built on the land of the Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin nation.

Credits

- Project

- In Absence

- Architect

-

Edition Office with Yhonnie Scarce

- Project Team

- Kim Bridgland, Aaron Roberts, Yhonnie Scarce

- Consultants

-

Builder

CBD Contracting

Planting selection Zena Cumpston

Structural engineer David Farrar

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin nation.

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2019

Category Public / cultural

Type Culture / arts, Installations

Source

Project

Published online: 26 May 2020

Words:

Louis Anderson Mokak

Images:

Benjamin Hosking

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2020