Awards for addiction are uncommon. It’s fortunate that architecture is addictive because it’s not always easy. The Gold Medal is a bonus for my addiction. I thank the Australian Institute of Architects, and in particular the award jury, for this honour, which I share with my mentors and collaborators, including my wife, Judith. It’s possible to contribute to the profession in various ways: through design, teaching, advocacy and research. I’ve had the privilege of contributing in all of these.

Outstanding contributions can be made by staff as well as the principals of architectural offices. While partners often survive downturns, employees are frequently retrenched, as I was on several occasions. Redundancies are setbacks but also opportunities. Like A. S. Hook, after whom this oration is named, I’ve spent most of my career as an employee. We both worked for the Queensland Department of Public Works, although a century apart. Employees’ contributions can be hard to identify, as demonstrated by Hook’s Queensland career, discussed below.

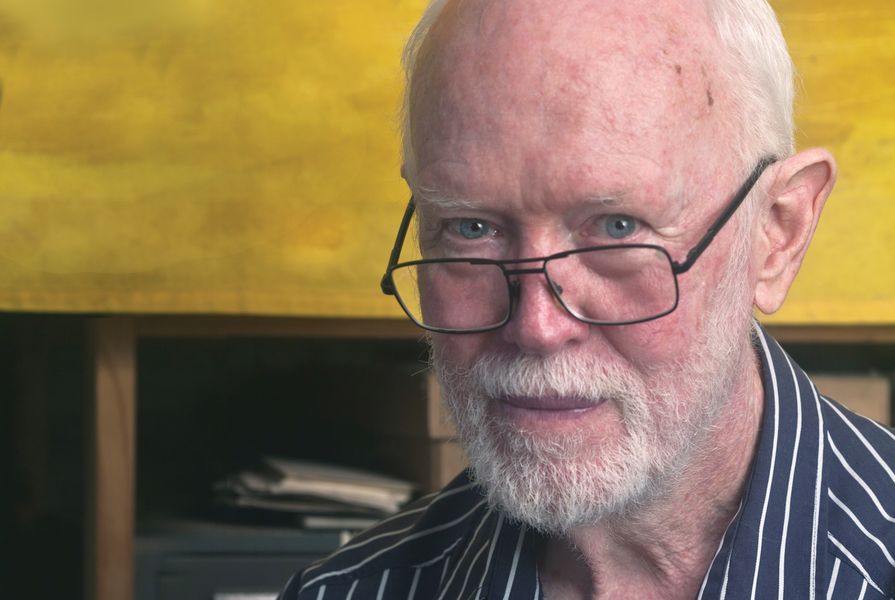

A. S. Hook

Alfred Samuel Hook.

Image: J. M. Freeland, <i>The Making of a Profession</i> (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1971)

The career of Alfred Samuel Hook (1886–1963) has been documented by John Maxwell Freeland, Rosemary Broomham and Philip Goad.1 Hook was born in England from a long line of plasterers. His father was a builder at Bournemouth, where Hook attended the local technical college before studying architecture at the Royal College of Art in London from 1905 to 1907, under the famous Arthur Beresford Pite.

Hook practised in Bournemouth before he visited Australia and decided to stay. After working in Queensland, he moved to Sydney in 1913, to the Government Architect NSW, and later to the teaching staff of the University of Sydney. Concurrently, he worked tirelessly for the profession, including towards the formation of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) in 1930. He became the body’s first president and was a long-serving office bearer, often in multiple roles.

In retirement, Hook wrote a detective story, The Coatine Case. As an architectural biographer, I’m also a detective, though details of Hook’s arrival in Australia elude me. When he came here in c. 1909, his intended destination may have been Brisbane, where his uncle George was a plasterer. According to Freeland, Hook was employed in Cairns by the Melbourne-born architect Harvey Draper. Hook’s presence in Queensland could explain two heritage-listed buildings of previously uncertain authorship: the Adelaide Steamship Company office in Cairns from Draper’s practice; and the Mount Morgan Post Office by the Works Department. Both are adaptations of the London work of Charles Francis Annesley Voysey and Charles Harrison Townsend, with which Hook would have been familiar. I surmise that after arriving in Queensland via Torres Strait,2 Hook designed the shipping office before moving to Brisbane, where he was associated with the comparable post office.

The Adelaide Steamship Company office in Cairns by Harvey Draper’s office, possibly designed by Hook.

Image: Pauline O’Keeffe, Cairns Historical Society

After tenders for the Adelaide Steamship Company office closed in Cairns on 18 December 1909, Hook embarked on the Arawatta for Melbourne, apparently taking the documents to the Company’s head office for approval to accept Wilson and Baillie’s tender. The Arawatta arrived on 29 December and approval was telegraphed to Cairns soon afterwards. Hook returned to Brisbane on the Ophir, arranging to meet Thomas Pye, Queensland Deputy Government Architect, on his arrival to seek employment. Pye was impressed but Hook “unexpectedly” returned to Cairns, possibly considering an offer of partnership from Draper. However, on 9 February, he accepted employment with the Works Department and returned to Brisbane, commencing work on 23 February 1910.3

Relating the Mount Morgan Post Office to Hook is conjectural; however, there’s no doubt that on 24 December 1909, en route to Melbourne with the Cairns plans, he spent the day in Brisbane. Given his intention to seek employment, I surmise that he could have shown the plans to Works Department staff. By the time Hook met Pye on 27 January, the post office design had been finalized and tenders called.

The Mount Morgan Post Office by the Queensland Department of Public Works, also likely to be Hook’s design.

Image: Queensland Department of Public Works Annual Report, 1914

The Works Department under Pye was an exciting workplace, with employees including John Smith Murdoch (who would later design Australia’s provisional parliament house), George David Payne and Evan Smith. Hook’s work for the Department (signed by him) included the fine administration block at the Ipswich Hospital for the Insane – now the Ipswich Campus of the University of Southern Queensland and heritage-listed. Wages in the Department were low and after two years, Hook accepted a position with the Government Architect NSW. Within a fort- night as a Designing Architect, his salary was raised to almost double his former Queensland salary. In Sydney, he worked on the Department of Public Instruction building on Bridge Street. But after a year, he regretted his move and sought, unsuc-cessfully, to return to the Queensland Works Department.

The administration building at the Ipswich Hospital for the Insane, now part of the University of Southern Queensland.

Image: Queensland State Archives, ITM580423

Other members of Hook’s family are less well known. His daughter Constance studied architecture at the University of Sydney in the 1930s before travelling overseas, where she married. She returned to Australia in 1948 as Constance Jackson and worked in Canberra as a town planner. After completing her architecture degree, she promoted modern architecture, opportunities for women and domestic crafts.

Hook’s younger brother, Percy Charles Hook, a builder and architect, followed him to Queensland. At Rock-hampton in the 1920s, he pioneered prefabrication of concrete houses and reinforced concrete construction.

Also little known is Hook’s compassion for pre-war refugees fleeing Nazi Europe, including architects George Molnar, whom he sponsored, and Karl Langer, for whom he found employment in Brisbane.

First steps

Totnes, Brisbane – Watson’s childhood home.

Image: Brisbane City Archives, B120-29688

Hook was precocious. Aged 10, he commenced study at the East Bournemouth School of Science, Art and Technology. He regularly topped examinations for scholarships to attend the Royal College of Art until he was old enough to be admitted. Some Gold Medallists have been younger: Hank Koning was three when he coloured working drawings for his father and 16 when he designed and built his first house.

I too showed an early interest in architecture. I grew up in Brisbane in a high-set timber house designed by Thomas Ramsay Hall in 1917. My block play followed the usual pattern: I began with early-childhood educator Frederick Fröebel’s so-called “gifts,” then moved on to English Bayko blocks, before using scavenged materials to build a model city in the dirt under the house.

Watson’s Campbell House, winner of the Australian Institute of Architects’ Robin Boyd Award in 1989.

Image: Richard Stringer

In 2009, the then owner of the Campbell House – which won the Australian Institute of Architects’ Robin Boyd Award in 1989 – asked me to speak about it. The project was my response to the clients’ request for a “Walter Taylor house,” reflecting the work of a local architect-engineer-builder. While mindful of Taylor, the house was quite different from his work, for complex reasons, and comprised a folded, one-room-deep, longitudinal gable. The internal angles were infilled with screened porches. Although I recalled the visual similarity to Bayko, I was surprised how closely the finished house evoked the blocks. Building-block historians Brenda and Robert Vale inexplicably conclude that Bayko was “utterly perverse,”4 but as STEM learning,5 its geometrical discipline was embedded in my consciousness.

To celebrate my Gold Medal, friends gave me a set of Bayko. This motivated me to buy a set of Anker blocks, designed by German architect Gustav Lilienthal, who practised in Melbourne from 1880 to 1885. In 1883, he applied for the post of Queensland Colonial Architect and competed for a new Brisbane Town Hall, losing in both to another prodigy, John James Clark. On returning to Germany, Lilienthal became a social reformer, developed prefabrication and assisted his brother Otto, a famous pioneer aviator.

Anker blocks were designed by Gustav Lilienthal, who practised in Melbourne in the 1880s.

Image: Gustav Lilienthal

My direct interest in architecture dates from 1952, provoked by my parents’ purchase of land for a beach house. Their excitement rubbed off as they looked for ideas, including in magazines. Among these was the March 1955 issue of Architecture and Arts and the Modern Home, guest-edited by David Saunders, which introduced me to the modern architecture of Europe and America, including Mies van der Rohe’s Edith Farnsworth House (formerly the Farnsworth House). Though I found this design weird, I was hooked. Instead of building at the beach, my parents commissioned Searl and Tannett to renovate our house. Des Searl presented me with perspectives of the firm’s recent work. I was soon able to discriminate between alternative plans for a three-bedroom houses of less than 10 squares (92 square metres). As a schoolboy, I regularly perused and occasionally purchased George Braziller’s Masters of World Architecture series.

About-turns

After practising successfully as an architect, Hook entered academia. I too have moved between practice and teaching, mostly due to circumstances beyond my control.

My first employer was James Birrell (Gold Medal, 2005). As architect to the Brisbane City Council and the University of Queensland, Birrell was of national standing. His Wickham Terrace car park in the Brisbane CBD and Union College and J. D. Story buildings for the University of Queensland were inspiring. He commenced private practice in 1966 with Lory Kulley, Richard Stringer and Philip Conn as partners. In 1967, Birrell’s Agriculture and Entomology Building was documented by University of Queensland students: Bruce Goodsir (sixth year) was in charge, assisted by Doug McKay (fifth) and me (fourth). I stayed nearly three years with Birrell, until I was retrenched when a major project was cancelled.

After a year with Hayes and Scott and some overseas travel, I worked from 1972 until 1974 for Geoffrey Pie, who was later to win the Robin Boyd Award (1986). During a real-estate boom, I worked on supergraphic-embellished renovations for a developer, Jack Roberts. When the boom ended and I was again redundant, these jobs led to commissions to design supergraphics for Brisbane Airport’s temporary international terminal and to renovate a city warehouse for a community arts centre.

In 1979, I was appointed half-time to teach design at the University of Queensland. After two years, my half-time appointment was rationalized to work alternate years. During my first year off, I worked for Frank Spork, who had been a colleague at Geoffrey Pie’s. Our skills were complementary, and I came close to entering partnership. In another year off, I worked on the Campbell House with John Waller.

After failing to receive a permanent academic position, I joined the Queensland Works Department in mid-1989, in antic-ipation of Queensland’s first Labor government in more than 30 years (the Goss Ministry). I later found my niche designing TAFE Colleges, with Don Hewitt as project manager and a team including Mike O’Brien, Katrina Marriott, Neville Twidale, Lee Wade, Mary-Anne Ammons and Greg Tunn, with Steve Gnatiuk and Wal Hardy as supportive clients. I wasn’t easy to work with, treating each job independently. The resultant buildings are related, but as half-siblings, with each also related to its context. The surrounding spaces were as important as the buildings themselves. In 2012, the Department’s Project Services division – the last intact major public works practice in Australia – was abolished by Campbell Newman’s Liberal National Party government.

Don Watson: A Civil Servant (2017), curated by Janina Gosseye, Douglas Neale and Alice Hampson.

Image: Michael Warrington

In 2017, colleagues led by Janina Gosseye honoured me by mounting an exhibition on my work. This was held in the premises of the Queensland chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects, a former warehouse skilfully renovated by Shane Thompson. For 76 years, the chapter (and its predecessor) had rented rooms, before becoming the first in Australia to purchase its own premises in 1964. Over the next 50 years and with successive purchases, the functionality and value of the chapter premises improved. For the exhibition, the auditorium walls were repainted to re-create my supergraphics for Brisbane Airport’s temporary international terminal. Together with a related sit-down dinner, this event demonstrated the value of chapter premises in fostering a lively architectural culture.

Sidestep

In Brisbane, the newly married Hook lived at suburban Toowong. After moving to Sydney, he lived at Lindfield, calling tenders in 1914 for a small brick cottage and in 1923 for additions. It’s possible that both tenders were for the attractive California bungalow he occupied during the 1930s. By 1943, he was living in Redlands, an Art Deco apartment building at Randwick.

Hook’s former home in Lindfield, c. 2010.

Image: onthehouse.com.au

In 1974, I purchased a mud-brick house in South Brisbane. It was in a state of collapse. It changed my life, leading to an alternative career and enduring interest. To inform my purchase, a librarian introduced me to post office directories – publications that provided information by locality, name (alphabetical) and trade. The 1883–85 volume listed residents of the street of my recent purchase. When read with the land title, I realized (as had others) that a coincidence of landowner and resident signified a building (that is, if the landowner was living on the site, it was an indication of a dwelling). Armed with little more knowledge than this, I obtained work with the National Trust to research the Queensland house. As an early researcher in this field, it was a great privilege.

Watson’s South Brisbane home when purchased in 1974.

Image: The Courier-Mail, 16 February 1974

In 1981, I reported on the significant differences between Queensland houses and houses elsewhere in Australia – not their planning, form or climatic adaptation, but their almost universal detached status; their predominant use of timber; their construction; and the unexpected role played by architects. Detached houses were explained by legislation6 that precluded the sale of individual terrace houses by establishing a minimum lot size of 400 square metres. With capital only slowly reimbursed as rent rather than quickly through sales, terrace housing was unappealing to speculators. The timber used was mostly softwood, not hardwood as previously contended.7 But both were important, with hardwood sourced from open eucalypt forests, and softwood and joinery timber from so-called “scrubs” – rainforest once extensive but now almost vanished from south-east Queensland. I looked at nineteenth-century surveys to understand the early landscape, interpreting its manicured appearance as the result of regular burning of the open eucalypt forest grasses, with fire contained by creeks or the fire-resistant scrubs.8

My discovery of early plans for Queensland schools explained the local tradition of outside studding and the architects responsible. I also found that buildings once attributed to bush carpenters were the work of architects. On visiting Barcaldine in 1976, I saw two houses that I suspected were architect-designed. Using post office directories, I was able to prove that there were architects practising in the Central West (and across Queensland). This led to the publication of two books: A Directory of Queensland Architects to 1940 (1984) and Queensland Architects of the 19th Century (1994), both with Judith McKay. In seeking to be comprehensive, we differ from many other Australian researchers, but not overseas biographical dictionary projects. In conjunction, I have been collecting architectural records for about 40 years to support the development of a major architectural archive at the University of Queensland’s Fryer Library.

In 1976, Watson proved that two houses in Barcaldine had been architect-designed around 1900.

Image: Don Watson

End of the path

In 1948, Hook retired from all positions in the RAIA and, three years later, from the University of Sydney. Having kept the Institute going during the Great Depression and World War II, he was unceremoniously replaced by a new generation. When the Gold Medal was introduced in 1960, he would have been a worthy recipient, but only after his death in 1963 was this oration established in his honour.

As previously mentioned, my career in the Works Department also came to an abrupt end. Unlike Hook, in my retirement I’m yet to write a novel, but I’m continuing my biographical research into the twentieth century and also trying to save other architects’ work. A recent success with saving Robin Dods’s Fenton, a residence in New Farm, led to the formation of a Queensland chapter heritage committee to nominate or support significant buildings for heritage listing.

I’ve also maintained an interest in design. To improve the Fryer Library’s storage facilities for its architectural archive, I participated with Jinx Miles in a heritage study of the University of Queensland’s Duhig Library, designed by Hennessy and Hennessy; we recommended that its original reading room be reinstated. The Gold Medal resulted in an invitation to run a master class that explored the adaptive reuse of the UQ Student Union (Stephen Trotter of Fulton Trotter Architects, 1959–) as an alternative to its proposed demolition. The resulting designs were well received and now at least some of the complex may be saved.

The future

Can any lessons be drawn from these parallel careers?

Hook’s early contact with building came from his family. By accident, I was exposed to architecture at an early age and my interest encouraged. The Australian Institute of Architects’ Education Committee is understandably concerned with academic standards of graduates, but I believe it could have more impact if attention were also paid to early-childhood STEM and design education as a foundation for both architects and their clients.

Not until after Hook’s death did the NSW chapter purchase premises, but for my entire career and up until recently, the Queensland chapter owned its offices. The void left by its sale will be more evident when the COVID situation returns to a new normal. I look forward to its replacement.

Hook was writing an autobiography but unfortunately its whereabouts and its state of completion are unknown. Recent moves to save the Institute’s records and make them accessible for research are encouraging and would bring us into line with our counterparts elsewhere, such as the UK’s Royal Institute of British Architects and Institution of Civil Engineers. I also hope that in the future, the Australian institute can collaborate with heritage departments and universities on a biographical project comparable with those in Scotland, Ireland, South Africa and elsewhere.

Finally, my generation has left this world in a fragile state. For young architects and students, within the years of their practice, the future of the planet will be decided. As practitioners, they will have to make good our failings and as a matter of urgency.

1. John Maxwell Freeland, The Making of a Profession (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1971); Rosemary Broomham, “Hook, Alfred Samuel (1886–1963),” Australian Dictionary of Biography (Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hard copy 1996), adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hook-alfred-samuel- 10535/text18703; and Philip Goad and Julie Willis, The Encyclopaedia of Australian Architecture (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

2. Records relating to arrivals via Torres Strait at that time have not survived.

3. WOR/A732 1913/367 Queensland State Archives.

4. Brenda and Robert Vale, Architecture on the Carpet: The Curious Tale of Construction Toys and the Genesis of Modern Buildings (London: Thames and Hudson: 2013).

5. STEM: science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

6. Undue Subdivision of Land Prevention Act 1885.

7. Philip Cox, John Freeland and Wesley Stacey, Rude Timber Buildings in Australia (London: Thames and Hudson, 1969).

8. Don Watson, “Clearing the scrubs of south-east Queensland,” in Kevin Frawley and Neil Semple (eds), Australia’s Ever-Changing Forests. Proceedings of the first national conference on Australian forest history, Department of Geography and Oceanography, University College, Australian Defence Force Academy, 1988, 365–92.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 28 Jun 2022

Words:

Don Watson

Images:

Brisbane City Archives, B120-29688,

Don Watson,

Gustav Lilienthal,

J. M. Freeland, <i>The Making of a Profession</i> (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1971),

Janina Gosseye,

Michael Warrington,

Pauline O’Keeffe, Cairns Historical Society,

Queensland Department of Public Works Annual Report, 1914,

Queensland State Archives, ITM3318430,

Queensland State Archives, ITM580423,

Richard Stringer,

State Library of Queensland,

Supplied,

The Courier-Mail, 16 February 1974,

onthehouse.com.au

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2022