Government dictates how housing is built in Indigenous communities. With incomes in these communities remaining low and private home ownership tenure on Aboriginal land being rare, this process is unlikely to change in the near future.1 “Indigenous community housing” refers to government-provided housing in Indigenous communities located on township leases on Aboriginal land.

In the last 50 years, governments have taken many approaches to Indigenous community housing, with both successes and failures. Typically, however, standard one-size-fits-all houses are rolled out in short-term programs with the argument that they are cost-effective and ensure fast delivery to address the chronic overcrowding issues faced in many Indigenous communities. While some current initiatives, such as the Northern Territory Government’s Room to Breathe program, aim to retrofit existing housing to be more inclusive and better meet the needs of residents,2 the benefits of designing-in a level of inclusivity, flexibility and longevity at the outset of construction to ensure better, more sustainable outcomes for residents continue to be overlooked.

A group of practitioners and researchers have undertaken projects and written about alternatives to current models for Indigenous community housing that echo each other at length. While some practitioners have focused on particular housing issues,3 their suggestions all share a focus on listening to, collaborating with and learning from the residents themselves. Despite repeated calls in Architecture Australia in 2004, 2008 and 2016 by researchers Paul Memmott and Timothy O’Rourke for a national database of Indigenous community housing that records and shares learnings from these experiences, this is yet to be taken up at scale.4 In 2018, architect Kieran Wong went so far as to say, “We cannot afford to ‘innovate’ in this space, with novel designs or construction techniques that satisfy a short-term need,” arguing instead for a “long-term national funding program for Indigenous housing.”5 If the profession has consistently shared the view that the solutions to inclusive Indigenous community housing are already available, why have they not been taken up? One argument, used by successive governments in national Indigenous housing programs, is that the collaborative process is too labour-intensive and time-consuming and leads to more costly design outcomes.

The story of one family’s transition to a new government-issue house in the Indigenous community of Yirrkala, in the Northern Territory’s East Arnhem Region, is useful in dispelling this myth and reinforcing calls for change.

Banbapuy’s story

Government housing approaches in Yirrkala have greatly varied in their inclusivity and ability to respond to needs. In 2017, the contract for new houses in Yirrkala was awarded to the local building collaborative Delta Reef Gumatj (DRG). While DRG trained local Yolŋu labour and used locally produced cement blocks and timber trusses in construction, the functional qualities of the houses remains unchanged from standard government-issue designs.

The story of Yirrkala resident Banbapuy Ganambarr illustrates the need for greater modification and diversity of existing housing to respond to individual requirements. In 2016, Banbapuy lived with her son and three grandchildren in a teacher’s house built from cementitious Yirrkala brick. When I met Banbapuy, her sister and family were also camping in her yard for a few months while they awaited the completion of their new house, after their previous one was condemned. However, after a car accident, Banbapuy was left with a disability and could no longer work as a teacher. Without rights to teachers’ housing, she was asked to vacate her house.

Banbapuy enjoyed living in the teacher’s house in Yirrkala because it was culturally appropriate and able to be adapted to meet her needs.

Image: Hannah Robertson

Banbapuy liked many things about the teacher’s house, which met her needs and was culturally appropriate. She explained that the storage nook near the entrance could be converted into a relatively private temporary fourth sleeping space when extra people came to stay. A separate kitchen away from the living and dining spaces created the privacy necessary to observe avoidance relationships and allowed multiple people to use the space without it feeling overcrowded. The separation of the toilet and shower enabled people to concurrently use the facilities, and the discreet location off the hallway avoided direct sightlines. Finally, Banbapuy’s bedroom was at the furthest end of the house, permitting her adult son to come and go without disturbing her at night-time.

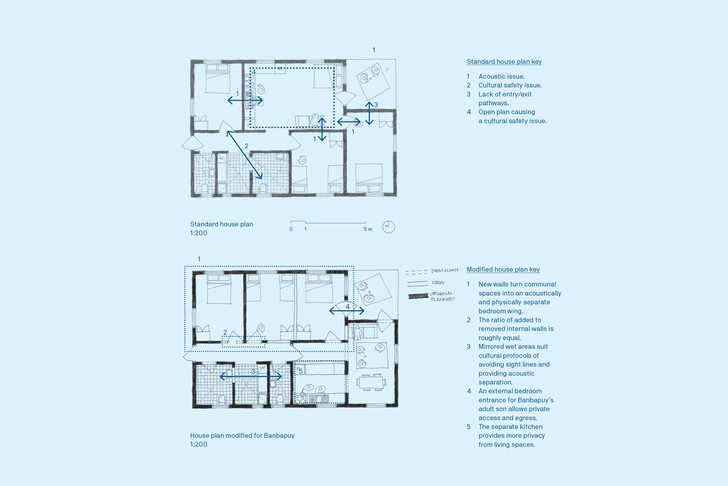

Knowing that she would need to move into a standard government-issue house, I accompanied Banbapuy on a visit to the house of an extended family member to look at the layout (all government houses in Yirrkala followed the same plan layout6). It was immediately clear that the standard three-bedroom house would not support cultural safety or provide general amenity for her and her family. Bedrooms were located directly adjacent to living spaces, presenting an acoustic issue. Direct sight lines were cast into bathrooms, posing a cultural safety issue. There was no separate entry for adult children to come and go without disturbing other members of the house. The open-plan living and kitchen area provided no separation of public communal spaces to uphold avoidance practices. The question was: could the layout of the house be improved to better meet Banbapuy’s needs and those of her family, without substantially altering its overall footprint?

To answer this question, I considered the layouts of Banbapuy’s teacher’s house and the government-issue house to draw up a modified proposal. In the proposed plan, new internal walls create a bedroom wing along one side of the house to provide acoustic and physical separation from communal public spaces. (The ratio of new internal walls to be built, versus existing walls to be removed, is roughly equal, meaning a negligible change in concrete block quantities.) Wet areas are mirrored to prevent direct sightlines and provide acoustic separation. A separate kitchen area improves privacy between living spaces. One bedroom gains a separate doorway, at the location of the original entrance, to provide private access for Banbapuy’s son . The net structural change to achieve these alterations is just one additional door. But the recommendations were never taken up because the local builder was contractually advised to adhere to the government’s set design.

The open-plan living and kitchen area provided no separation of public communal spaces to uphold avoidance practices.

Image: Supplied

A more inclusive approach

Banbapuy’s story illustrates one Indigenous community household at one point in time. However, it is a situation common to many Indigenous community residents. And although the design proposal to meet Banbapuy and her family’s needs will not meet the needs of all families across Australia’s Indigenous communities, her story highlights a potent aspect of Indigenous community housing: there is not only a shortage of houses, but also, very few houses respond to the needs of the occupants. The modifications proposed for Banbapuy’s house indicate a wide range of possible adaptations that could be made to better suit the needs of other families. These modifications are cost-effective and do not substantially alter the existing structural system.

While there is a long-term need for architectural practitioners and researchers to continue to agitate for governments to heed recommendations for a national database of Indigenous community housing, to learn from past research and projects, and to include residents in the design process from the outset, the following steps can be taken now to prove that inclusive design need not be more expensive:

- Listen to residents and ask questions about their needs as soon as they are assigned a new dwelling.

- Equip community housing service providers to adapt standard designs to fit the needs of residents (provided there is minimal change in overall building quantities, structural system or footprint).

- Enable building contracts to allow for design amendments (provided they do not lead to cost overruns on construction).

- Document and review the relative success or failure of each approach so that it can contribute to the long-term vision for a national database of Indigenous community housing that can be used to inform evidence-based best-practice policymaking.

While the net structural and cost change of implementing this approach may be as simple as one additional door, the net change of providing a family with a home that responds to their needs and cultural protocols extends over the service life of the house.

1. The risk of Indigenous land status being lost and the lack of a private market in which to buy and sell assets means that private ownership on Indigenous land is rare, although discrete examples exist.

2. Northern Territory Government, “Our Community, Our Future, Our Homes: Room to Breathe,” 2019, ourfuture.nt.gov.au/about-the-program/room-to-breathe.

3. For example, Paul Pholeros, Stephan Rainow and Paul Torzillo’s focus on health and safety in Healthabitat; Geoff Barker’s insistence on the inclusion of universal design principles; Paul Memmott, Christina Birdsall-Jones and Kelly Greenop’s focus on overcrowding; and Shaneen Fantin’s emphasis on cultural considerations.

4. Paul Memmott, “Aboriginal housing: Has the state of the art improved?” Architecture Australia, vol 93 no 1, 2004, 46–48; Paul Memmott, “Delivering culturally appropriate Aboriginal housing,” Architecture Australia, vol 97 no 5, 2008, 61–64; Timothy O’Rourke, “Sharing plans for Aboriginal housing,” Architecture Australia, vol 105 no 5, 2016, 37–8.

5. Kieran Wong, “We need to stop innovating in Indigenous housing and get on with Closing the Gap,” The Conversation, 31 May 2018, theconversation.com/we-need-to-stop-innovating-in-indigenous-housing-and-get-on-with-closing-the-gap-96266.

6. The proposed house design in Yirrkala was developed centrally in Darwin and the same design is built elsewhere in the Northern Territory, including in desert settlements such as Alice Springs.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 24 May 2022

Words:

Hannah Robertson

Images:

Hannah Robertson,

Supplied

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2022