I have a love-hate relationship with the drive to my mother’s house. As an Indigenous woman whose family has been disconnected from Country due to colonial processes, I am on a journey of reconnecting, so I relish the opportunity to move through Country and connect the landscape with the cultural knowledge I’m learning. As I drive from my home in Gundungurra Country, I think about the stories I have been told. I think about the 330-million-year-old mountains created during the Dreaming, the rivers and hills formed by creator spirits awakening from their slumber. As I move through Mulgoa Country, I remember the stories of the Black Swan people that speak of their plight during the last ice age, 11,000 years ago. I admire the beautiful golden hills and plains, imagining the Dharug people cultivating murnong, hunting emu and burning the land. As I drive along roads that travel the same lines as ancient murus, I think about the songlines and the paths travelled by the Old People and wonder whether my ancestors were some of them. I look across Country and see the impact colonial land management has had, but take pride in knowing that there are mob reclaiming land and relearning practice. As I travel, I think of the abundant opportunities to restore these practices and dream of the ways in which we can reconnect with Country and work together to heal it.

However, as I move through these beautiful hills toward my mother’s place in Dharawal Country, my dreams are interrupted by the continued colonial onslaught. The rolling velvet hills give way to seas of black roofs, their encroaching shoreline marked by tides of newly cleared, terraced plots of land. It’s as if the rolling h ills never existed. The opportunities for this generation and the next to work together to heal Country, to reconnect, disappear. Country has been erased. Nothinged. Torn up and flattened out, ready to be replaced by the suburbs.

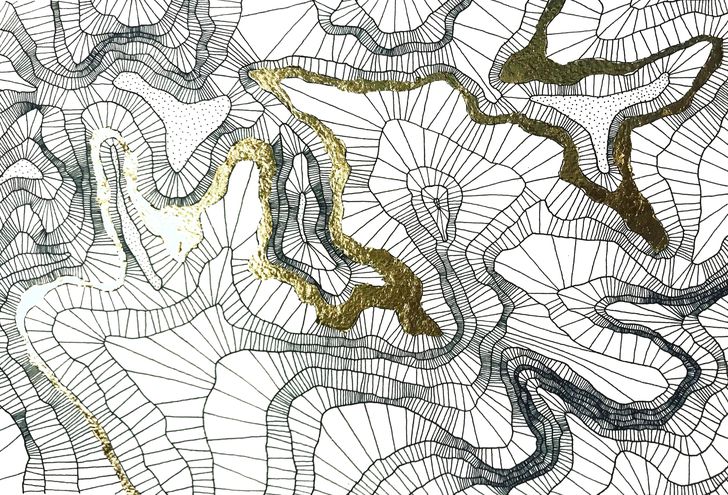

Home by Kaylie Salvatori.

As a landscape architect, I am alarmed by the developer-led suburban sprawl that typifies Sydney’s west. The ecological and social trade-offs with suburban sprawl are well known: food security and biodiversity loss, the urban heat island effect, increased energy consumption, unsustainable changes to flow regimes, an increased waste burden and traffic pollution, to name a few. From a placemaking perspective, the business-as-usual approach to suburban development often leaves much to be desired: the new streets are ubiquitous and placeless, with little to distinguish one new township from another.

As a first-time homebuyer, I understand the appeal: affordability and space and, in some cases, relatively convenient access to amenities (including some stellar parks). While these perks come at the cost of time in longer commutes, more extreme weather and perhaps the loss of the vibrant culture of city villages, I understand the need for space and affordability. I empathize with the people who move to these insta-communities, but feel there are questions to be asked of the developers and mechanisms that have allowed these types of developments to become the norm. With Greater Western Sydney pegged to house more than 50 percent of greater Sydney’s population by 2040, we can and should do better. Country deserves more.

For an Indigenous woman, the trade-offs of this type of development cut a lot deeper. They represent the ongoing violent colonial occupation of Country – the human-centric approach typical of Western modes of habitation imposed on sacred Aboriginal lands without concern for our ongoing connection to Country. This type of development works to erase histories and physical links to our ancestors; it threatens habitat for ourselves and our kin – plants and animals – stymies reconnection for present and future generations, and presents a lost opportunity for the wider community to learn about culture and know Country.1 In the name of developer profits and housing affordability, sacred rights and connections continue to be damaged and intergenerational trauma is perpetuated. These developments go against our basic tenets of caring for Country. They take too much and give back too little.

While in Western paradigms land is considered an abiotic medium on which to grow and build, Indigenous concepts of Country are much more holistic. We regard Country as kin and as having agency, while also being a place of healing, a place of belonging to which to return. Country connects us with the Dreaming, our ancestors and the generations to come.2 The rights and responsibilities associated with Country are eternal and cannot be sold, bought or traded.3 We have duties, rights and obligations to keep it healthy; in return, Country takes care of us. In this paradigm, we exist as equals with plants, animals and insects; we are all kin, with roles to play in maintaining the health of the system. In this respect, our worldview is highly relational, focusing on interconnectedness and ideals of reciprocity and shared responsibilities.4 The practice of caring for Country – effectively landscape design and management, but also much more – is integral to the expression of culture.5

As such, the human-centric development of land that typifies suburban sprawl is at direct odds with our cultural practice and ethos and presents a continuation of colonial processes that seek to take too much from Country. In order to dismantle these colonial processes, collaboration with Indigenous people and the practice of caring for Country must be integrated into the processes, outcomes and protocols of design. To this end, policies, literature and approaches are being developed to guide designing with Country instead of against it. Last year, the New South Wales Government Architect released the Connecting with Country Draft Framework. Developed in collaboration with leading First Nations academics, knowledge holders and designers, the document provides a framework for change. For a rich and deep understanding, I invite you to consider the seminal work of leading Indigenous academic and fellow Budawang woman Danièle Hromek, whose thesis The (Re) Indigenisation of Space: Weaving narratives of resistance to embed Nura [Country] in design6 provides in-depth insight into the complexity of Country and Indigenous relationships with space.

At my workplace, Arcadia Landscape Architecture, we have been developing and improving our methodology and approach to collaborative design in order to develop authentic Indigenous landscape strategies. When asked to provide my perspective on suburban development, a project we are working on in Awabakal Country sprang to mind as a great example of collaborative Indigenous design. For this project, we have engaged with local Indigenous authorities and Traditional Owners from the inception in order to develop a suite of design strategies and protocols that, if adhered to, could yield a new type of suburban development – one that works with Country, in partnership with community.

This process has been a new experience for the cultural collaborators and has been a rewarding and educational process for the design team, who are learning more about First Nations culture and Country every day. Through a collaborative approach, we have developed a suite of design strategies that consider people within the context of Country – protecting sacred sites and trees, keeping ridgelines free and equitable to access, and protecting, conserving and regenerating habitat for plants and animals. Importantly, the strategies include making culturally safe places for Indigenous people to practise, learn and express culture and explore opportunities for partnerships that will provide a perpetual benefit to the Traditional Custodians. Embedded throughout the design are opportunities for the wider community to learn about Country, Indigenous culture and history, with the aim of fostering cross-cultural exchange, learning and pride in Indigenous identity. Most of the site will be undeveloped bushland, with further implications on lot size, Passive House design, planting and materiality to be explored as we move through the next stages of design. It is an exciting project and, provided the integrity of the original intentions are maintained throughout all stages of the project, will likely become a leading example of Country-oriented design – and therefore sustainable design – that I hope will operate as a catalyst for collaborative Indigenous urban design across Australia.

What if approaches like this became business as usual? What if the development of Country was something done in partnership with Indigenous people, instead of in spite of us? Just as the built environment has historically functioned as a spatial expression of colonization, so too can design work as a vehicle for change. Acknowledging, respecting and valuing Indigenous agency and knowledge of Country is an active part of decolonizing our approach to design, but it also works the other way: if industry does not collaborate, it continues its complicity in the colonial mechanisms that deny First Nations culture and diminish the agency of Aboriginal people. As our agency as custodians of Country is indivisible from our culture and healing, a fundamental step in Indigenous rights and advancement involves the broader community realizing, learning and acting on these rights that have been practised for millennia. From a pragmatic perspective, if collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders is adopted as a fundamental, business-as-usual approach to urban development, it could yield broadscale, tangible benefits to the broader community as a whole – including ecological benefits, cross-cultural exchange and knowledge sharing, food security, health and wellbeing. We need to find ways to live with and within Country – if we keep taking too much, there won’t be anything left to nourish us.

I acknowledge and pay my respects to the First Peoples of the unceded lands I live and work in. I pay my respects to Elders past, present and future, whose knowledge and wisdom ensures the continuation of Country and culture. Always was, always will be.

— My name is Kaylie Salvatori. I am a Yuin Budawang woman working as a senior landscape architect and Indigenous landscape strategist at Arcadia Landscape Architecture. I am an artist, designer, partner and mother living in Gundungurra Country, exploring my connections and relearning about Country and culture. Though my thoughts and experiences are likely shared by many Indigenous people, unless otherwise stated, the thoughts presented here are my own perspectives as an Indigenous woman living in contemporary Australia and are not intended to speak for Indigenous people as a whole. I am thankful to my ancestors, Elders and Blak mentors for guiding me through my journey and hope to do my part in giving back to community and Country.

1. Danièle Hromek, “The (Re)Indigenisation of space: Weaving narratives of resistance to embed Nura [Country] in design” (PhD thesis, University of Technology Sydney, 2019), eprints.qut.edu.au/200158/ (accessed 23 April 2021).

2. Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? (Broome: Magabala Books, 2014).

3. Hromek, “The (Re)Indigenisation of space.”

4. Hromek, “The (Re)Indigenisation of space.”

5. Jessica K. Weir, “Connectivity,” in Australian Humanities Review , issue 45, 2008, 153–64, australianhumanitiesreview.org/2008/11/01/connectivity (accessed 23 April 2021).

6. Hromek, “The (Re)Indigenisation of space.”

Source

Discussion

Published online: 6 Jul 2021

Words:

Kaylie Salvatori

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2021