Photographs Toni Wilkinson.

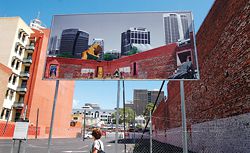

Iredale Pedersen Hook’s billboard for The Architects Project, a “gazebo” covered with images of unrealized designs for Perth.

Jonathan Lake Architects’ billboard, at the corner of Wellington and Milligan Streets, projects a new proposal against the existing skyline.

Simon Pendal Architect’s billboard, Wellington Street, a comment on the changing city.

Gresley Abas Architects’ billboard on St Georges Terrace, a satire of development hoardings.

Callum Morton’s billboard shows St Georges Cathedral as a roller-coaster ride.

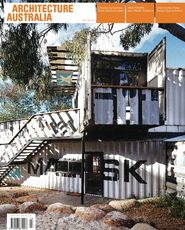

William Taylor contemplates the Architects Project, installations for the Perth International Arts Festival.

Repeated calls over the years for architecture to be given a seat at the Perth International Arts Festival – along with theatre, music, dance, literature, cinema and visual arts – were answered this year with the inclusion of the Architects Project on the 56th annual festival program. The project entails the installation of a series of billboards in the CBD and Northbridge. Four were designed by young Western Australian architects and emerging practices – Iredale Pedersen Hook, Jonathan Lake Architects, Simon Pendal Architect and Gresley Abas Architects. A fifth installation was prepared by Melbourne artist Callum Morton, who represented Australia at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and whose work commonly adapts and redeploys iconic architectural images for satiric effect. Unfortunately, despite the considerable talent enlisted for this exercise, the results are liable to disappoint the viewer.

To be fair, disappointment is more likely due to the underlying concept, terms and medium set for the project by festival organizers than to any particular fault of any designer or their installation. Overblown expectations were established at the outset by festival publicists, inviting us to “walk the streets of an imagined Perth and wonder at the fantastic structures proposed for vacant lots in the city centre”. Festival publicity was full of grand schemes and high aspirations. “Unusual, provocative or simply beautiful,” reads the festival website, “the fanciful structures challenge our views of how we conceive of space in our city.” In the attempt to stage-manage one’s viewing of the project in this way, these slogans remind one of other, equally exaggerated claims already spread across Perth’s vacant lots and billboards by developers promising new structures and spaces for consumers with cashed-up lifestyles. However, compared to the size and ubiquity of the city’s building sites and hoardings, the relatively modest scale of these festival projects and the obscure placement of one or two undermine their collective visual impact and any intended sequencing and message they might have.

Given these constraints, the projects are considered well enough. One itinerary starts with Iredale Pedersen Hook’s project for a site on the corner of James and Lake Streets in Northbridge. It takes the form of a billboard and elongates and bends it into a kind of skeletal gazebo, its raised and curvilinear surface covered with images of unrealized designs for Perth by architects past and present. The extent of information conveyed and the curved reading surfaces turn the viewer’s experience into a spatial one, though given the heat of the day, these circumstances also make for an uncomfortable reading of a kind unintended by the scheme’s designers. Crossing the pedestrian footbridge into the CBD, one catches sight of Jonathan Lake’s billboard at Wellington and Milligan Streets. This depicts a largish, spongiform building against a skyline which more or less reproduces the real one perceptible from the bridge. Here the problem of scale is most obvious, as one can only really see the image for what it is from a much closer and lower viewpoint. Further along Wellington Street, Simon Pendal makes a statement about the ongoing changefulness of the city, though the position of this third vacant lot removes it from most pedestrian itineraries. Jumping across town to St Georges Terrace, the site for Gresley Abas’s project is somewhat less removed, but equally in need of greater visual prominence. This is a satire on the mixed messages carried by many development hoardings promising fashionable yet environmentally sustainable lifestyles.

Morton’s project, an image showing Edmund Blacket’s St Georges Cathedral turned into an amusement park roller-coaster ride, affords only momentary interest and lacks the insightfulness and sustained humour of projects included in his show at the Perth Institute for Contemporary Arts last year. Situated on the grassy lawn in front of the church along St Georges Terrace and across from Council House, the billboard is admittedly the most visually striking of the five. The prominence of the site, however, in an area that former WA Premier Richard Court wanted to turn into a heritage precinct and facing an iconic modernist building that many of his constituents wanted to tear down, seems to call for a more didactic and politically challenging response than this. Political and cultural establishments as well as ecclesiastical agencies have long taken citizens for a joy ride in pursuit of questionable goals and one wonders what past or future reality this graphic one-liner was meant to invoke.

It is a difficult and potentially expensive task to incorporate architecture into an arts festival, particularly if one is thinking of projects to compete with the scale of real-life buildings and city skylines. Even curators mostly familiar with the conventions, installation and presentation of visual art (as narrowly conceived) would likely see the missed opportunities here to engage the myriad ways architecture defines our experience of an urban realm. These are often modest and quotidian means, arising from the transitory character of experience rather than leading to its representation through bold statements and iconic or satiric imagery. For example, despite the spatial novelty of Iredale Pedersen Hook’s project, it is all too easy to forgo the time required to appreciate its message, due to either the heat of the day or the darkness of nightfall. Perhaps much of the information on the gazebo would have been better placed on cafe menus (an opportunity for public-private partnerships and joint publicity, perhaps?) and the vacant lot left in its empty, mournful state to be contemplated over a latte. Perhaps the experience imagined by Lake’s sponge-like building could have been complemented, heightened or challenged by opportunities to enter building sites and go behind hoardings to witness some “other” urban reality behind the narratives developers and festival curators spin that tell us all how we ought to live. Perhaps a lottery could have been devised, affording the lucky winner an opportunity to push a demolition button and create an empty lot of their own, to live in a luxury flat for a day or to turn the lights off a high-rise to save the earth a moment’s worth of carbon emissions.

Through a partnership between the Perth Festival and sponsors Wesfarmers Arts, the Architects Project is the first of a series of art installations intended to “enliven” the CBD during festivals for a four-year period. One only hopes that this first effort will not dissuade all parties involved from keeping architecture firmly, but more effectively, on the agenda. One hopes that subsequent organizers and “concept” authors will seek the ideas of young architects and established artists from the outset, to set the terms and medium for likely briefs, to provoke thinking on ways the city is already enlivened, to propose ways that urban experience may be enhanced and to provide more than two-dimensional images of future possibilities.

Bill Taylor is professor of architecture at the University of Western Australia.