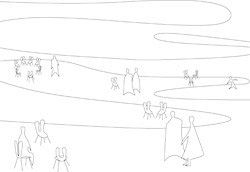

Concept sketch by SANAA of the installation held for the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation.

Overview of the installation at the Sherman Gallery in Sydney.

Nishizawa arranging the “Rabbit chairs” (designed by the architects) for the installation.

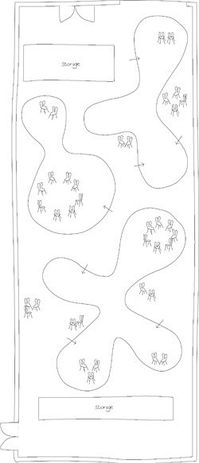

Diagrammatic plan for the installation.

An installation by Ryue Nishizawa and Kazuyo Sejima of SANAA, discussed by Sandra Kaji-O’Grady.

The opening of an installation by Ryue Nishizawa and Kazuyo Sejima of SANAA at Sherman Gallery on a cold but clear Thursday night in July attracted many of Sydney’s architectural luminaries – Penny Seidler, Glenn Murcutt, Wendy Lewin, Brian Zulaikha, Tim Greer, Neil Durbach, Camilla Block, Alex Tzannes, Richard Johnson, Bridget Smyth, Angelo Candalepas and many others. Equally present was the younger generation of emerging architects – Chris Bosse, Marcus Trimble, Matt Chan, Patrick Keane, etc. Academics Leon van Schaik and Helen Norrie had flown in from interstate. Like me, they were drawn by their appreciation of SANAA’s strongly conceptual architecture and the rare pleasure of an architectural exhibition in a reputable contemporary art gallery.

The ambitions of Sydney’s white minimalists and those of SANAA are not comparable; nevertheless, one could not imagine an audience more sympathetic to and knowledgeable of SANAA’s oeuvre and their formal moves. Yet the neutrality of the installation confounded many of us – if we were looking for new insights into their work, a spatial argument or, simply, sensual affect, there was none to be had. The installation is comprised of vertical sheets of curved plexiglass and SANAA “Rabbit” chairs in beech – designed by the architects and commercially produced by nextmaruni. The plexiglass and groups of chairs are arranged so as to force a meandering path through the single space of the gallery. It’s a tactic for organizing space in the absence of enclosing rooms that they have developed over a succession of projects undertaken together and in their separate architectural practices.

The Glass Pavilion for the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo, Ohio, completed in 2006, is the most likely progenitor of the exhibition. It’s a single-storey building made up of a series of curved glass walls that impose indirect perambulation at the same time as they permit direct, albeit layered, views across the various programmatic activities and outside to the park in which the building is fortuitously sited. The most present formal element at Toledo is the horizontal white plane of floor and roof. As at the Rolex Learning Center at the Federal Polytechnic School in Lausanne, which is now under construction, vertical structure and enclosure are visually and dimensionally diminished to the point where they are experienced as an absence or erasure.

The intention of this vertical dematerialization at both Lausanne and Toledo is to replicate the experience of walking in a garden. In his invite-only talk before the opening, Nishizawa referred to the importance in his work of “nature” – though it is clear that in the Japanese landscape tradition of stroll gardens and cherry blossom festivals, “nature” is that which is improved by acts of pruning, potting and selective planting that serve to intensify, condense and miniaturize the medium. Only after such manipulation is nature available for communal activities of contemplation and contrived pleasure, exemplified by the cherry blossom festival.

If ambiguities between enclosed and external space and the blurring or leakage of space between rooms and courtyards are at the heart of the SANAA project, then this perhaps is why their installation is ineffective. In dimensional terms it responds to the space of the gallery, but there is no other engagement, no outside being brought in. Moreover, and unlike minimalist works by artists such as Dan Graham or Donald Judd, the installation does not come out of a concerted effort to understand and complicate the voyeuristic relationship between space, objects and the human body. Dan Graham’s glazed pavilions and room installations of mirrors and delayed video projection, for example, intend a kinaesthetic disorientation that makes apparent the act of viewing at the same time as the relationships between individual viewers are uncomfortably highlighted. In a sense Dan Graham’s work doesn’t exist without a viewer – photographs of it do nothing to illuminate its effects or intentions. It requires the presence of a viewer to be complete, something critic Michael Fried called “theatricality” and found to be a failing of many of the minimalist projects of the 1960s, such as those by Donald Judd. SANAA’s installation has the opposite problem – it is solipsistic; the chairs and plexiglass talk to each other and the viewer is redundant, left out of the equation. The problem does not occur in their buildings, where the act of living or working or viewing an object of art fills the void. There is nothing to view or to photograph until the buildings are occupied.

In conclusion, the difficulty for SANAA is that this installation does not come out of a lineage of art practice, be it theirs or others’. One would not want to draw up territorial lines that discount the value of architects venturing into the physical and institutional space of art. Not only does the gallery offer freedom from the constraints of building regulations, budgets and client requirements, it opens up opportunities of engaging spatially and conceptually with art history and concerns, with different audiences and at scales or in materials unacceptable to permanent building. Crossing into art practice allows architects an opportunity to push their material and conceptual investigations further, to reframe and rework their interests more intensely, either for its own sake or to return to architecture reinvigorated. My expectations of the SANAA exhibition were that this opportunity for transformation and experimentation would have been taken up with passion. What we got instead was a material fragment of their architectural interests relocated into the gallery. The event in no way detracts from the significance of their architecture, but at the same time it does not take it to new heights or to new audiences.

Dr Sandra Kaji-O’Grady is associate professor and head of architecture at the University of Technology, Sydney.