PHOTOGRAPHY Andrius Lipsys

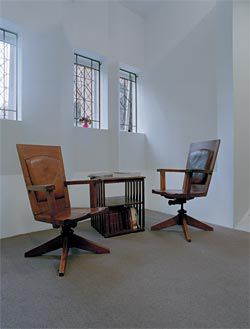

The refurbished anteroom at Newman College carefully organizes a collection of Griffin furniture, along with 1950s bookcases.

Looking into the anteroom from the oratory, on the upper floor of H Wing. A gateway is formed by two 1950s bookcases. The design of the new acoustic screens attached to the rear of the bookcases draws on an office wall the Griffins designed for Nissen Leonard-Kanevsky in 1922, but at an amplified scale.

The open-plan main administration area, on the ground floor of H Wing.

A new study-bedroom interior in the Kenny Wing.

The Dean’s room, located in the H Wing ground floor, showing the Griffins’ original furniture.

The law library.

Paul Morgan Architects’ recent refurbishment of part of Newman College respects the heritage fabric while also generating a range of productive dialogues between old and new. Review by Tracey Avery.

Heritage architecture is not for the faint-hearted. This is doubly so when the architect is confronted with the interiors and furniture of one of Australia’s most iconic buildings of the twentieth century: Newman College, the women’s residential college at the University of Melbourne, designed by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin between 1915 and 1918.

Bound by the principles of the Burra Charter, the philosophy for any new work is a central concern for heritage projects. The charter argues that new work should be clearly distinguished from the old. The more common approach to achieving this visible difference is to introduce contemporary elements devoid of detail that would refer to the existing styles of decoration. An alternative position is to make that difference more subtle by referencing the existing design. The latter can be achieved purely through colours or materials or, more daringly, by adapting design details. A combination of these approaches has been used in different parts of Newman College in recent conservation work by Paul Morgan Architects.

Each of the spaces tackled by Morgan raises different dilemmas for conservation philosophy. The main administration area is now open-plan. Later partitions were removed from this area, successfully revealing the window arches, which give a rhythm to the entire space. A modern white paint has been applied, and the greater light reflected from the relatively small original windows reduces the reliance on artificial light. The main meeting room for the college has been created in a partially glazed space carved out of the former reception area. This area is of intimate dining proportions. Surrounding glass and white walls plus original table, dining chairs, framed prints and drawings contribute to a modern Arts and Crafts appearance.

The college’s oratory has had its function revived and extended to become a multipurpose communal space. Entered from the rear of the room, the initial space functions as an inner hall or anteroom, which is enclosed by a bank of two bookcases that form a gateway screen to the lecture space. The bookcases, which date from the 1950s, have had their leaded lights conserved. Attached to the rear of the bookcases is a newly designed acoustic screen, patterned with intersecting, deeply moulded chamfers. Griffin’s manipulation of these elements was more finely dispersed in the office wall for Nissen Leonard- Kanevsky at Leonard House, Melbourne (1922). Nevertheless, the proportions of the chamfers on the screen are bold enough for this cavernous space. Consequently, the detailing of the servery is less successful – a plain surface would have been an option given the form of the surrounding furniture.

Again, the anteroom contains a selection of the Griffins’ original furniture for the college, which has been reassembled from previously stored pieces to create what Morgan refers to as a mise en scène. Although disparate items of furniture have been gathered to fill this space, the scale and placement of the pieces, including two commodious sofas, avoids any hint of the stage-set quality sometimes found in museums and historic houses. They are clearly “in use”.

The final block to be built at Newman College was not designed by the Griffins, but allowances had been made for its placement. This came in the late 1950s with the Kenny Wing for more student accommodation, which echoed the original style. Its interior consists of exposed brick walls and plainly moulded wooden doors and architraves, which is more utilitarian in feel but characteristic of the time and lacking the “distraction” of decoration. The brief to Paul Morgan Architects for this block was to create study-bedrooms with new fitted furniture and paint schemes.

Although this building is itself a reinterpretation of the Griffins’ original design language, some historical underpinning was again sought for the style of new work. Under the direction of Sophie Dyring, inspiration for historical reference was taken from the work of prominent women designers of the early twentieth century, including Eileen Gray. However, the built-in cabinetwork has a pattern of cupboard doors in white with some framework in black, more akin to a De Stijl construction. Functionally, the whole unit contains bookshelves and a washbasin, plus cupboards and drawers. The arrangement and colour scheme resembles the myriad storage compartments in Gerrit Rietveld’s 1924 house for Truus Schröder-Schräder in Utrecht. Though the style has been employed successfully, it does raise the question of whether such a choice needs to be justified because it is part of a heritage project.

Viewed through the lens of Modernism, the more historicist approach has been avoided in recent times, possibly for fear of comparisons with the nineteenth-century architectural “restorers”, who were much derided for their mixing of old and new work by critics such as William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB). Yet Arts and Crafts architects were not averse to gaining design inspiration from conservation projects. For example, Scottish architect Sir Robert Lorimer disliked over-restoration, but freely designed new architectural elements and furniture based on earlier models, often taken from collections in South Kensington and the Rijksmuseum.

Paul Morgan Architects is to be congratulated for confronting and testing a range of solutions to conservation and the introduction of new elements. Creating a dialogue between the old and new work reduces the harshness of the “stripped modern” approach. A degree of design homage here generally respects the original and gives the interiors of the college a greater feeling of gradual evolution, one in keeping with the significance of the original design and the buildings’ continued occupation.

›› TRACEY AVERY IS A CURATOR AND PHD CANDIDATE IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE.