Model of Los Llanos auditorium.

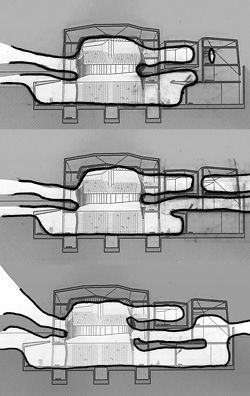

Sectional diagrams for the Magma Arts and Congress Centre.

Magma Arts and Congress Centre, Menis Arquitectos with Felipe Artengo Rufino and José Maria Rodriguez-Pastrana Malagón. Photographs Menis Arquitectos.

Finding value in what exists – Enlai Hooi speaks to Fernando Menis.

It’s high tide. Two loops of steel protrude from a nest of rocks overswept by the twilight swell. Handrails and tread plates call attention to a swimming zone within the rocks. It’s not hard to see why they were put there. The natural basin may have been a wading zone for hundreds of years. This kind of simple gesture, utilitarian and assuring, is the kind of thing communities instate for themselves when their budgets belie their aspirations, where scarcity imposes a kind of invention that stems from seeing potential in scrap or in the shelter offered by a certain natural formation.

It is in precisely this environment that Fernando Menis grew up. Tenerife – the largest island in the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago off the west coast of Africa – does not benefit from any significant cross-trade of goods or materials. What is not found or made on the island has to be imported and the cost of this is rarely attractive. In its isolation, Tenerife generates a kind of self-sufficiency; a make-do creativity comparable with what we find in parts of Australia, where a bit of wire will suffice for almost anything. In Menis’s work, the limits imposed by the location offer a way to focus and organize his efforts. It has led to a mastery of certain materials and a work method dedicated to extracting the most from the urban environment in which the building lives.

A building designed by Menis Arcquitectos will typically comprise concrete or stonework quarried locally, timbers from the region and remnants of other structures that were demolished during its construction. Menis’s approach to bio-regionalism is not so much a moral decision as it is an application of commonsense. It comes from rational choices on behalf of the client, the builder and the local community. The local mason understands the stone to the point that all of its peculiarities can be exploited to reveal its formal and structural qualities. The carpenter understands the nature of his timber. It makes financial sense and minimizes waste. When the capabilities of locally available materials are exhausted, Menis’s studio will search for other means of constructing what they need. They term this process “recycling” – a process Menis developed as a child.

To entertain himself, Menis constructed his own toys from the leftover parts gleaned from his father’s watch-mending business. Disused parts were reconfigured – their functions reimagined for a different purpose. His kind of recycling sits outside the realm of the contemporary practice of “re-virginizing” a product or a material. Menis’s buildings incorporate lighting systems constructed from reclaimed plumbing lines, stairs made from an oil storage tank, and furniture from leftover formwork. The effort, here, is to find value in what exists. It relies on the act of reimagining the possibilities present in artefacts rather than forcing things back into a homogenous state. It is the natural activity of a child and, in fact, a natural condition of our imagination – but one that is often forgotten by architecture in its habit of directing the energy of others from a distance. What is built comes from the architect’s imagination, product literature and line work, not the stuff that exists on the demolition site. Menis’s practice focuses on this kind of “recycling” as a central theme and line of research. This notion extends beyond the material to the revision of attitudes and cultural practices. Much of Europe now survives on the tourism industry. The firm is engaged in establishing a positive reinterpretation of tourism where the value of a place lies in its cultural specificity, “allowing the inhabitants of the place to feel integrated rather than displaced by the new situation” according to Andreas Ruby.

Menis’s notion of recycling is intricately tied to a sense of place which extends beyond the simple mechanics of “site conditions” to an empathy with the character of the site itself. From this perspective, a building grows in response to the needs of its users, balanced with the specific nature of its location. An appreciation of place takes time and research. It requires that designers visit the site and, most importantly, dedicate their attention to the spirit of the place. Louis Sullivan’s notion that “a proper building grows naturally, logically and poetically out of its conditions” is exemplified in Menis’s buildings. His response to location is insightful and disarmingly uncomplicated. In an interview with Menis, the fifty-seven-year-old architect explained the point with childlike animation:

“You are a global architect, yes. But when you are an architect for the beach, you are an architect from the smallest point of the world. You are an architect from that rock! You must stay in the place, feel where is the sun, where is the wind, think how is the water come up and down, the people, everything …”

Menis Arquitectos spend a great deal of time on cultural and site analysis. They imagine the possibilities of what might come to be, and reflect this in the studio through models, discussions and material experiments. The judicious use of model-making materials directs the imagination, forms and texture of Menis’s architecture. Moving back and forth across a range of modelling materials, the studio works to develop a sense of surface, form, colour and weight for a project simultaneously, picking out specific qualities sought from each.

For the development of the Los Llanos Auditorium, Menis Arquitectos found samples of local stone and split them in the studio to determine the forms that were possible from the material. Model making and material enquiry are deeply rooted in the processes of the studio. In Menis’s eyes, the shape or characteristics of a project can be implicitly led by the material qualities of the model and the architect must learn to value “the specific consequences that accompany this choice”. It leads to outcomes, such as the Los Llanos Auditorium and the Magma Arts and Congress Centre, that appear to arise from a violent rupture of the earth. These stereotomic megaliths appear to be incised from the ground on which they stand. Their interiors capitalize on this impression: compressive spaces marred by the remnants of pneumatic chisels and rough-hewn formwork suddenly billow into massive interior volumes at the threshold of performance spaces.

The metaphor is particularly present in Los Llanos, where many of the interior volumes resemble lava ducts that can be found in the subterranean landscape throughout the volcanic island. The use of this analogy is not altogether cursory. In fact, it is the simple and direct result of the acoustic requirements of the space. It made sense to build the shell of the building in angular, crystalline forms. The process offered practical construction opportunities and suited the language of the site. It also made sense to divorce the interior volumes so that acoustic modelling could direct the shape of the space. The distance between the interior and exterior surfaces allows for the necessary passage of air and the location of other services that would otherwise occupy additive forms within the space. In construction, the interior is simply hung from the shell. The simplicity and clarity of this approach characterizes much of Menis’s work.

Menis’s projects vary in style, cost and complexity. Although Menis has a style, it isn’t treated like a brand and isn’t applied to every project. The consistent feature in his studio’s work is the response to the conditions of the place. This response has engendered such varied designs as the Spreebrücke – a floating swimming pool on the River Spree in Berlin made from a derelict barge, a public park in Santa Cruz whose morphology adapts to the original topography of the site and recalls the form of lava flows, and Casa MM, Menis’s own house, which incorporates salvaged parts from a nearby oil tank. In the house, galvanized water pipes are used in the exterior shading system and rescued steel forms the primary staircase. Commenting on the design, Menis makes the point that while the upper flights are hung from the roof level, the lower flights are anchored more solidly to the structure. “I have to think about the time that I am sick. When I am sick, I want my foot to touch the solid material. This is my home.” This kind of personal concern is evident when he formulates the program for a venue or deals with his clients’ concerns.

Even in the Magma Arts and Congress Centre (a joint project between Menis, Felipe Artengo Rufino and José Maria Rodriguez-Pastrana Malagón), arguably the most audacious of Menis’s projects, his personal concern for the director and the operators of the building is clear. “One thing is to find the money for building; the other thing is to find the money for the maintenance. Normally a public building eats a lot of money and you must pay every month … What happens now the economy collapses? If you have a good program [and the building makes money], this is very important … the building can live from the visitors. You don’t have to rely on the government.” Magma itself has been designed with careful attention to the program. A comprehensive study of the urban situation led to program variations that allow the building to support itself in between performance and conference schedules. The results of this are reflected in the attitudes of its users: “I go to speak with Pablo, the director. On his computer, he doesn’t have the picture of the wife … he doesn’t have the picture of the children. He has the picture of the building! What happen, really, he love the building … we try to make the building for the people. Some architects work only for architects. And I think … architect is only three percent of our society. So we must understand where it is we work.”

It is unusual to ascribe a product to a personality. Most of the time there is a disjuncture between your favourite book and its author. Menis’s work is at once arresting, inventive and compassionate. Perhaps this is one instance where the person can be seen in his work.

Enlai Hooi is a designer, teacher, writer and student of architecture. Fernando Menis was brought to Australia by the Cement and Concrete Association as part of the CAA+ Talks series.