The front entrance of the house/studio, surrounded by the native landscape of Perth.

Image: Peter Bennetts

There is a long tradition of architects using their own homes for experimentation in design, building and inhabitation. Produced within the conditions of a tight budget, direct materials and limited time – the usual reality of an architect’s income and resources – the most fascinating speculations in space, material and form emerge. Classic examples include Ray and Charles Eames’s own house in Pacific Palisades, Frank Gehry’s house in Santa Monica and contemporary Australian projects such as John Wardle’s and Sean Godsell’s widely published homes and Corbett Lyon’s Housemuseum – all of which demonstrate a deep exploration into ways of living.

Arguably, this tradition is richest in Western Australia, where access to large, relatively affordable blocks of land and the injection of wealth from successive mining booms provide an opportunity for architects to apply their ideas through the construction of their own homes. Examples include Desmond Sands’ home in the beachside suburb of Cottesloe and Ross Chisholm’s house in the exclusive enclave of The Combe, among others. The mineral boom of the 1960s was particularly fertile, with West Australian government and industry aspiring to communicate Perth’s affluent position, encouraging a generation of young architects to communicate progress by embracing the influence of Modern architecture.

The entry facade, showing detail of the experimental cast concrete exterior.

Image: Peter Bennetts

There was also a steady flow of immigrant architects and engineers keen to exploit the opportunities of the “New World.” The young Bulgarian architect Iwan Iwanoff arrived in Perth in 1950 and worked in several reputable offices before branching out on his own. Legend has it that he first ran his office from a two-bedroom apartment in East Perth before relocating to Floreat – a Western suburb adjacent to the stadium at Perry Lakes, built for the 1962 Commonwealth Games and a potent symbol of “Modern Perth.”

It was in this context that Iwanoff designed a house in which he could work and raise a family in the idyll of the West Australian coastal suburb. The Iwanoff House is a clean diagram, with the studio on the ground floor and the residence as a single level hovering above. Iwanoff brought a distinctly European Modernist sensibility to his interpretation of suburban living: essentially an apartment with a balcony over “the shop” – or in this case, the architect studio. Yet it is sited in suburban Perth, with native landscape flourishing around and under it.

A plane of concrete screens a west-facing window from heat and glare. Artwork: Marie Hobbs.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Iwanoff intimately understood the local landscape. He balanced the house within the site by connecting the expansive rear native garden to the street via the carport void, located directly within the fabric of the building. This allowed direct visual access (now altered). Floating cabinets on the first floor concealed a concrete grille where air was drawn in and escaped through another grille above the upper cabinetry, providing natural ventilation throughout the year. A large floor-to-ceiling glass pane on the western side of the building sat behind a plane of concrete, allowing light to permeate the house without exposing it to the harshness of the western sun.

On the upper level, floating timber cupboards line the walls. Artworks: Guy Grey-Smith (on stand), Marie Hobbs (hanging).

Image: Peter Bennetts

The interior of the house revealed Iwanoff’s commitment to “total design,” with rigorously detailed solutions for storage and flexible use of space. On the upper level, floating timber cupboards lined the walls above and below the strip windows. Iwanoff designed his own furniture specifically for the house, including the dining table with two identical tabletops, one sitting under the other for flexible configuration. Two small living rooms were separated by a screen wall – now removed – which facilitated one space to be used as a sleeping area when required. Transitions between spaces were economical, with curtains dividing bedrooms and passageways.

Indeed, the house embodies many qualities evident in Iwanoff’s collective body of work, most present – probably due to budget constraints – are the experimental use of ordinary materials in “organic” or expressionist applications and the adaptation of vernacular building techniques into elegant construction solutions. For example, direct, functional but flexible planning is combined with the expressive assemblage of standard concrete blockwork and experimental cast concrete exterior.

Since Iwanoff’s death in 1986, two subsequent owners have occupied the Iwanoff House. Interior designer Julie Hobbs and her husband David Leith have raised three children there since 1994. The challenge for the Hobbs/Leith family lay in adapting the dwelling to the needs of a growing family while respecting its architectural legacy. For Julie, a design practitioner and educator, it was important to balance her respect for the architect’s work with a rejection of the notion of a house as a museum. “The longer I lived in the house,” she says, “the more I felt Mr Iwanoff wouldn’t want the house to stand still in time.”

The ground-floor studio. Artworks L–R: George Duerden, Jukunda Mona Chuguna, Ted Snell, Mary Moore, Julie Hobbs (vase), Nina Kierath (sculpture), Julie Sylvester (glass sculpture), Queenie McKenzie, Trevor Vickers, Mabel Juli, Jinny Bent.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Primary changes included occupying the ground floor for family living, Iwanoff’s studio becoming an additional living space and study for Julie’s own design work, and the original carport being converted into a master bedroom, which removed the spatial connection between the street and rear garden. Aware of the significance of such a move, Julie worked in collaboration with her architect brother, Peter Hobbs, to achieve a sensitive modification, striving to keep the feeling of transparency through the use of glass walls and references to original joinery in the bedroom’s screening device.

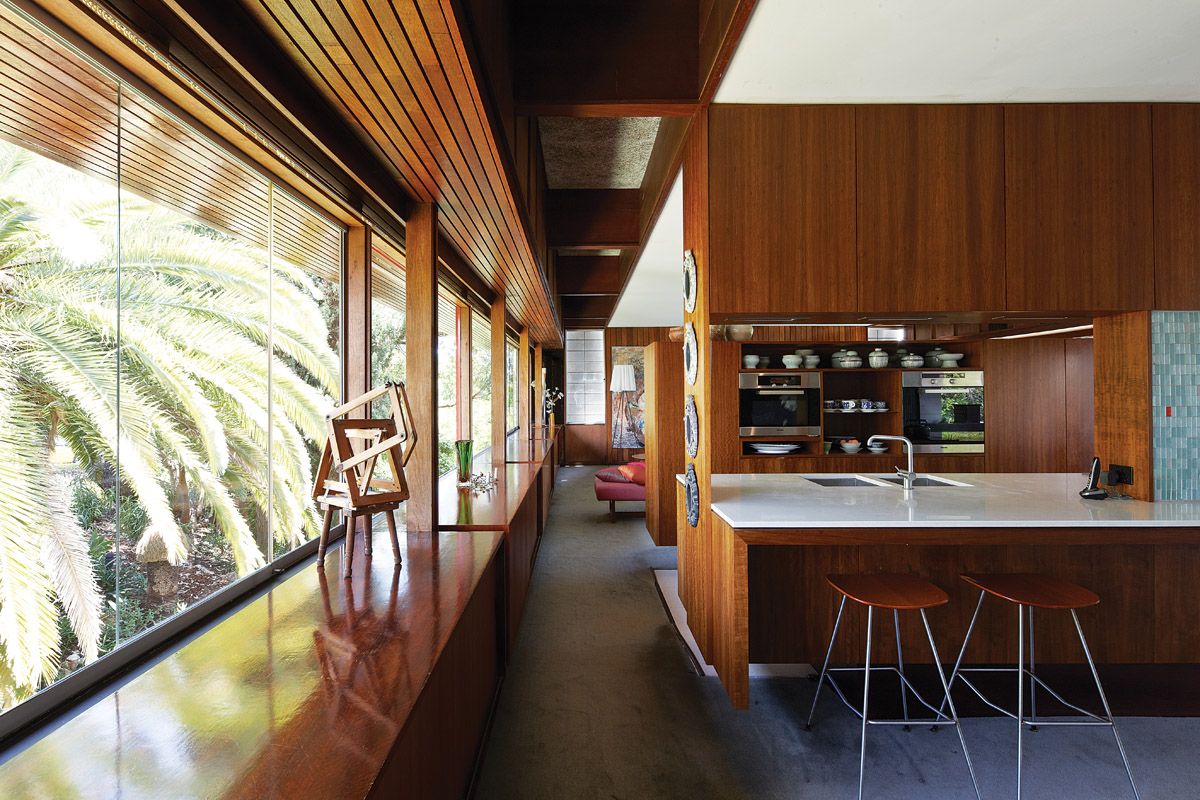

The new kitchen was placed in the footprint of the original. Artwork: Theo Koning (sculpture).

Image: Peter Bennetts

On the first level, the greatest challenge was the renovation of the kitchen, which had suffered over time through lack of maintenance and water damage. Replaced in the exact footprint of the original, the new kitchen had to work with Iwanoff’s original design for the plumbing system, where downpipes taking water from the roof’s box gutters ran vertically through the kitchen joinery. Details such as the curve in the glass mosaic tile splashback are a result of the need to accommodate this function.

While the original back-to-back bathrooms from the two first-floor bedrooms still have original marble walls and sliding mechanisms for the cabinetry, new stone-top vanities have been added for additional storage. The entry’s terracotta mosaics – some damaged during renovations – were replaced in parts with splashes of coloured glass mosaics. An investment in a new roof was required, and the upper terrace was renovated, asbestos removed and sunshading reorientated, while the Corbusian strip windows were painted a rich imperial red intended to be read from the street. Julie felt more confident with these shifts over time, as the family grew into the house and it became very much their own.

Original 1955 drawings of the house, with the studio on the ground floor and the residence above.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The house is filled with artworks, including the work of Julie’s artist mother and a striking collection of West Australian and Indigenous artworks. Iwanoff would undoubtedly have approved of this addition, stating in an interview in 1979: “Art is very neglected in our homes [yet] it should be fundamental to them … When we draw up plans, we plot pictures and other artworks in the legend … [marking] positions for ‘paintings by Western Australian artists.’”

The challenge, of course, for the occupier of any significant piece of residential architecture lies in balancing the role of guardianship with finding a way to live naturally and at ease with the architect’s intent for the project. What might we learn from a house such as this, in terms of a progressive, adaptive, economical and yet culturally responsive residential architecture? And what lessons might it hold for its neighbours – old and new?

At the time of writing the Iwanoff House was for sale and has subsequently been sold.

This review is part of the Houses magazine Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- Iwanoff house

- Architect

-

Studio of Iwan Iwanoff

- Project Team

- Iwan Iwanoff (1919–1986), Peter Hobbs, Julie Hobbs

- Site Details

-

Location

Floreat,

Perth,

WA,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

- Client

-

Client name

Iwan Iwanoff

Source

Project

Published online: 25 Nov 2011

Words:

Fleur Watson

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Houses, June 2011