Gateway: a visceral response

The Gateway installation, a collaboration between architect Norman Foster, artist Charles Sandison and film director Carlos Carcas, used sound and image projection to investigate the broader issue of a common ground in architecture.

The installation contained two elements and based its research on the history of architecture and of the public spaces of the city. Firstly, there was a sequence of frequently changing still images projected onto all four walls. These images – sourced from a global network of architects, designers, planners, photographers and critics – covered Western history, the new cities of Asia and South America, and the crisis of the favelas.

The places in the images were connected by their significance in terms of social change, and were interspersed (infrequently) with images of large internal public spaces such as stadiums, museums and transport hubs.

The second element was a white illuminated text animation that projected the names of influential architects onto the floor and raw brick columns of the building. The animation was intended to represent the virtual structures of colonization and multiculturalism in Singapore, and the adaptive behaviour of its citizens. Sandison drew from his extensive studies of ant-colony behaviour to generate computational algorithms that influenced the animation.

Watching the audience’s immediate visceral response was interesting. The installation clearly had an impact on people, who engaged with the animation and reflected on its content. Observing the responses gave rise to a couple of questions: Can architecture better communicate to a broader audience through the lens of other disciplines? Can we increase understanding about the culture of architecture by communicating its value to society?

While questions currently abound about the emergence of alternative modes of practice – indeed they were the fundamental to the Australian pavilion at Venice 2012 – for me, the Gateway installation also raised questions about the equivalent need for alternative modes of representation.

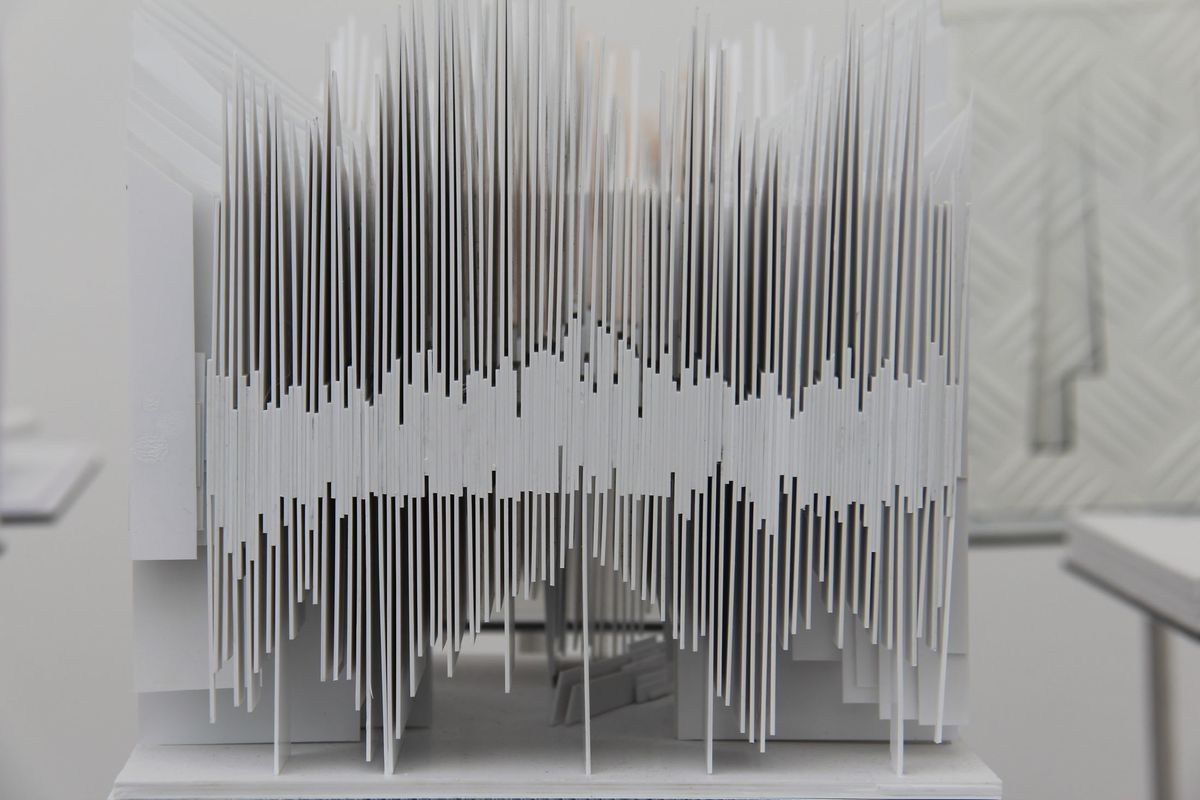

Hungarian pavilion: space maker

Hungarian pavilion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Image: Joanne Taylor

In 2010, Hungary’s BorderLINE pavilion was a highlight of the Venice Architecture Biennale. The use of almost one hundred kilometres of ropes weighted by individual pencils produced a three-dimensional flexible space that communicated how the two-dimensional line of the pencil literally turns into architecture. It was both poetic and dramatic. In 2012 Hungary followed its own lead with Space Maker, which shifted the focus from the line to the architectural model.

Within the boundaries of the grid, steel rods emerged from the ground supporting an equal number of small white models to form a “model-forest”; the models were all sourced from a collection of students’ tenders from Hungary and other European countries.

In an elegant way, Hungary’s 2012 pavilion became the inverse of the 2010 pavilion, containing within it the same affection for a linear treatment, but this time transitioning from the ceiling to the ground plane. Both exhibitions sprang from the same family of thought and said something of the value Hungary places on some of the most fundamental acts of architecture. Its message was clear, simple and precise, and effective: “Why change?”

The theme of Common Ground was explored through the cooperation that occurs between students at a domestic and international level. The fact that it avoided saying anything new about architecture so as to emphasize the elegant coolness and cleanness of the installation could be forgiven because it celebrated the creative, playful and explorative temperament that’s part of our profession. It also exposed the endless investigations that form a collective intelligence.

The sculptural installation used the pavilion as a larger model to contain a series of smaller models and, just as the 2010 pavilion did, it made for a good photograph. While its seemed that for the second time in a row the audience was captivated by Hungary’s pavilion, I will be curious to see whether its next installation will offer a fourth dimension.

Japanese pavilion: the collaborative model

Japan’s Golden Lion-winning pavilion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Image: Joanne Taylor

Representing alternative housing concepts for homes destroyed by the earthquake and tsunami in 2011, the Japanese pavilion, Architecture. Possible here? Home-for-all, was an in-depth representation of a collaborative process that focused not just on an end solution but which envisioned a new way of practising architecture as part of a collective team.

Models varying in both scale and materiality were displayed on sawn logs exposing a behind-the-scenes sequence of what occurred when three emerging architects – Kumiko Inui, Sou Fujimoto and Akihisa Hirata – came together with the pavilion’s commissioner, Toyo Ito, to produce a support centre for victims in the tsunami-affected city of Rikuzentakata.

The temporary centre was a base for community regeneration, and gave people who had lost their homes in the tsunami somewhere to connect. The context of a disaster zone (with its associated loss) was seen as providing the perfect opportunity to investigate architecture from the ground up and rethink its future.

Developed over a six-month period, the design connected a series of relationships between businesses, private individuals, local authorities, architects and local residents, who at all times were involved in the decision-making process.

While many pavilions at the 2012 biennale represented the Common Ground theme by celebrating individual voices coming together, the Japanese pavilion was one of few that merged the personal and professional identities of individuals into a solution and into a new and unified form.

With cities currently growing at unprecedented rates, and with much of this happening through spontaneous informal developments – people are literally making the city – the Japanese pavilion demonstrates the power of collaborative work by architects in shaping not only the future of cities, but also the future direction of practice. The Japanese pavilion won the 2012 Golden Lion for Best National Participation at Venice for very good reason.

Dutch Pavilion: space invader

Re-set, the Dutch pavilion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Image: Joanne Taylor

Re-set, situated within the Rietveld building, was a subtle but effective installation that explored how an existing piece of architecture can be crafted into twelve new situations.

The Rietveld building has been vacant for forty of its fifty-eight years. The Olanda installation merged the imagination of over half a century ago with that of present day by intercepting the building, rather than merely placing something on exhibition within it. Its aim in doing so was to highlight the value of architects working in areas of rehabilitation.

Within the space, a series of curtains was hung from a large ceiling-mounted track that moved in response to a set time and program that literally re-set itself every ninety-six seconds. While the curtains were the same scale, the materiality, colours and textures changed in configuration, allowing for moments of transparency, reflection, absorption and seclusion.

Re-set stimulated a need for constant physical readjustment within the space, and parallels could be drawn between the immediacy of the environment and the larger context of a fast-paced changing world. The temporary division of the space prepared us for the next move while keeping us aware of the transience of the last: one moment you were enclosed, the next you were exposed.

The body was able to shuffle in and adjust to divisions around the space. This in itself was a somewhat foreign experience.

Re-set succeeded in its aim of breathing new life into old foundations and opening up new qualities and new uses for the building, though on an experiential level, it did much more than this. Through its inversion of the spatial experience, it challenged our understanding of our relationship to space: the moving body became the fixed object, and the static space became the moving object, demanding that new interaction develop between space and object.

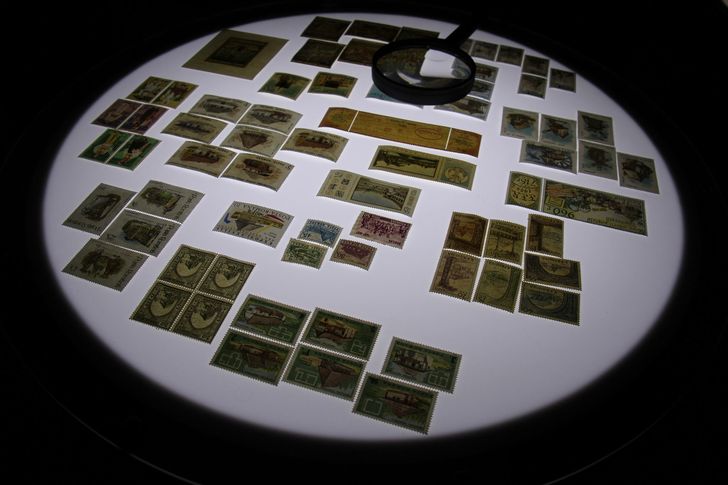

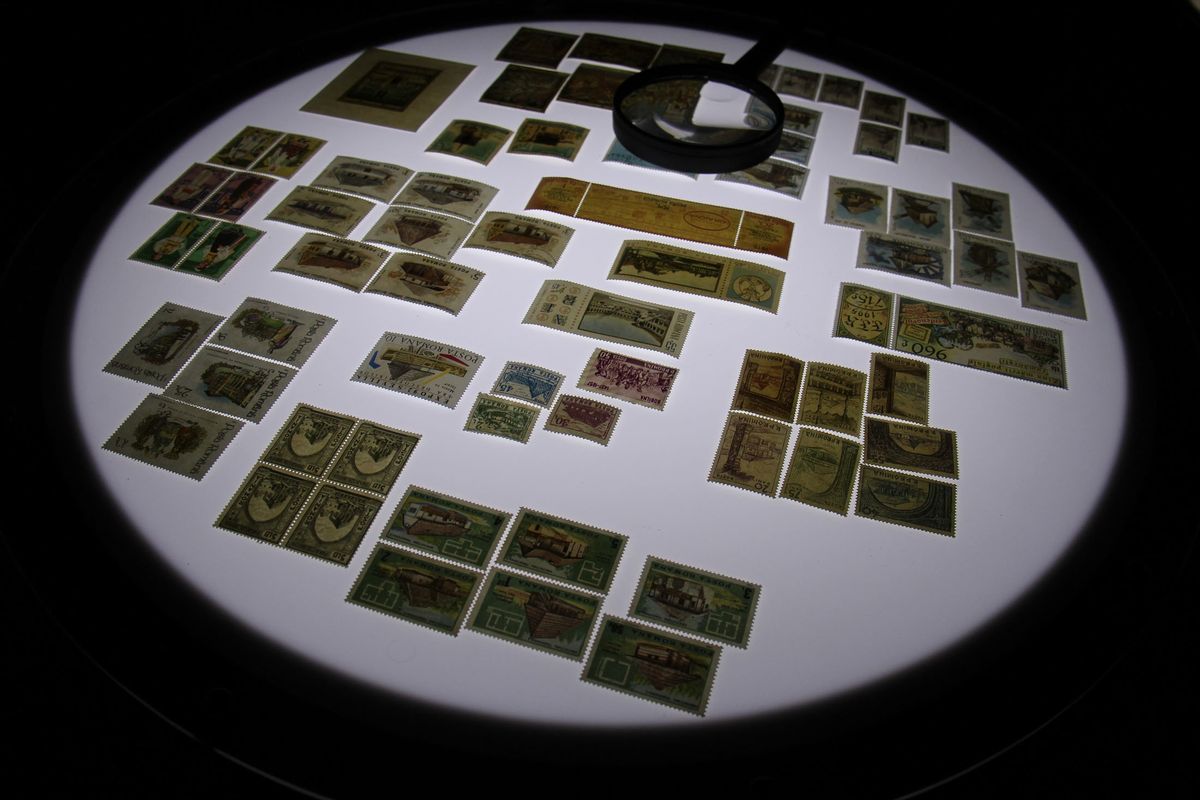

Romanian pavilion: stories within a stamp

Stands in the Romanian pavilion displayed three types of stamps.

Image: Joanne Taylor

The Romanian pavilion explored the theme of Common Ground though its use of the stamp, and used the Play Mincu exhibit (an invented interactive game) to expose the bureaucracy and officialdom that controls Romania’s architectural profession.

The concept of the game was influenced by the activities of Romanian architect Ion Mincu, who was deeply involved in both the political and bureaucratic fields of architecture. By using the game as a cultural act, the installation drew attention to the restructuring needed within architectural bureaucracy.

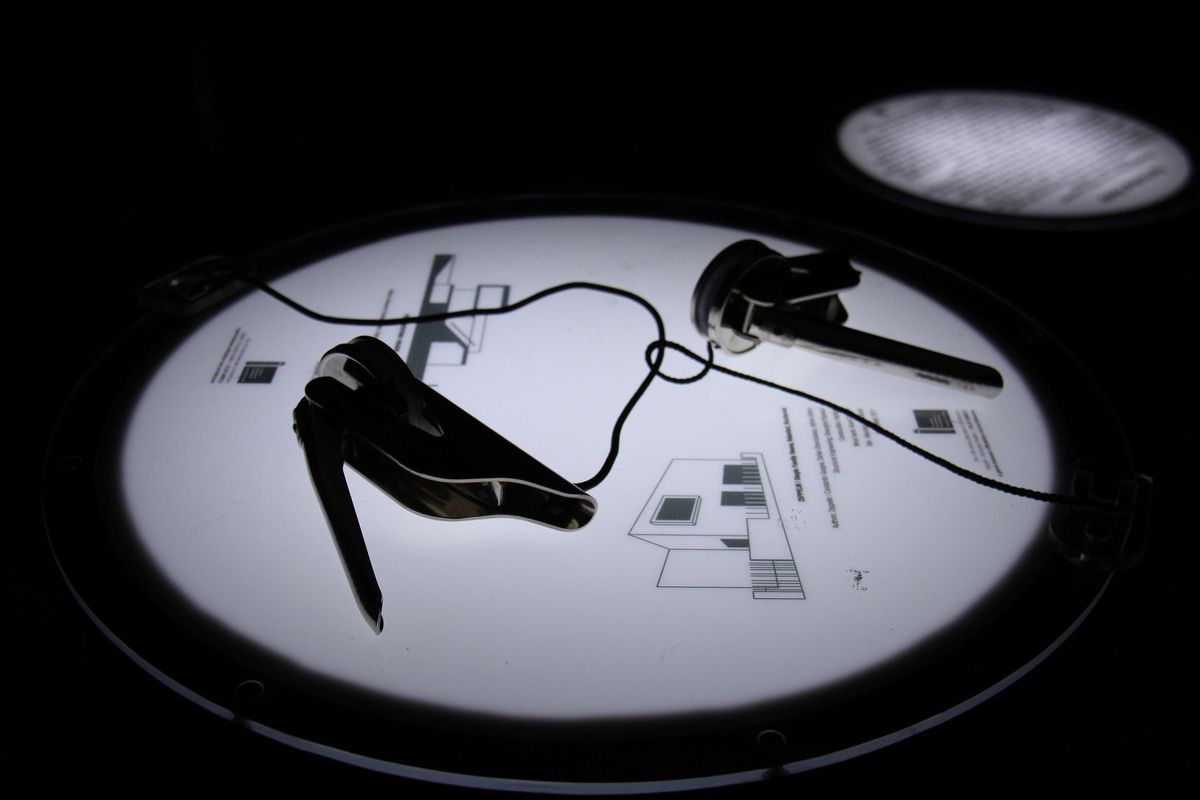

Inside the room were black circular stands, a dim light emanating from their opaque white tops. Each displayed one of three stamp types: the architecture stamp, the notary seal emboss or the sonorous stamp.

The architectural stamp has a dual symbolism. Firstly it is a revenue stamp that states whether the beneficiary of architectural services has paid the tax required to the professional organizations of architecture, and secondly it is a postage stamp, printed with important civic architectural works. These postage stamps were collected and displayed as symbols of recognition of the role that architecture plays in cultural identification.

The notary seal emboss recognizes the three levels of bureacracy that an architect in Romania has to navigate. In this exhibition, its attempt to turn bureaucracy into a playful object involved the audience in a tactile operation. Each stamp in this category contained a visual imprint of Romanian architecture; on entering the pavilion, visitors were offered a piece of paper on which they could have their choice of dry stamp imprinted. It then needed to be “coloured” over with pencil to reveal the imprint. The staged process drew attention to the constant struggle of the profession in trying to free itself from the boundaries and constraints of bureaucracy that affect practice.

The sonorous stamp represented the dematerialization process occurring in a global culture. Our shift towards and preference for the virtual over the material was symbolized through a coloured scanning of a real stamp that had been transformed into sound. Each stamp in this category was embedded with quotes from influential architects or artists, and the visitor chose which imprint they would have on their sheet of paper. Every time a stamp was imprinted, the sound of that stamp was released into the space. This process posed the question of whether or not this is a new form of officialdom.

The Romanian pavilion was richly layered with thought. By operating on both the critical and physical levels it engaged the audience into thinking about the message behind the installation, while at the same time leaving visitors with a personalized memento to ponder.

Any exhibition that raises the critical questions surrounding the survival and progression of the architectural profession should be commended for contributing to the ongoing conversation on the subject. The Romanian pavilion did just that, and while it focused specifically on its own common ground, through the playful sounds of Mincu, it delivered a more sobering message about the struggle against bureaucracy that architects the world over share daily.