Sketch by Philip Kirke of the historic Warden’s Court and Post Office, site of the Kalgoorlie Courts Project.

The site of the Kalgoorlie Courts Project, the 100-year-old Warden’s Court and Post Office Building. These are part of the Government Buildings complex, which included the Post and Telegraph Office and Public Buildings. Designed by the Public Works Department under the direction of its principal architect, John Harry Grainger, the Government Buildings were built in local pink stone, and completed in 1897. Photograph Geoffrey London.

“Break-away” Country near Windidda, Eastern Goldfields. The jurisdiction of the Kalgoorlie Courts stretches across a vast area of Western Australia, from Esperence on the coast of the Great Southern Ocean up to parts of the Northern Territory.

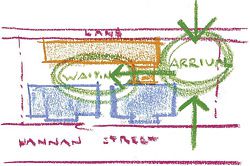

Diagrammatic sketch of the planning strategy – the outdoor spaces form the central organizing principle of the plan.

View from the proposed central public secure courtyard looking towards public gallery space. The tilting glazed doors are seen open.

View from the public gallery across the central landscaped courtyard towards the historic building.

In 2007 Hassell was engaged to undertake an exhaustive regime of consultation leading to the design of a major contemporary courts complex in the remote regional town of Kalgoorlie, in the heart of Western Australia’s productive goldfields. At the time of writing the project has been completed to detailed Design Development phase.

The Kalgoorlie Courts Project includes three magistrates’ courts, two jury courts and a range of mediation, registry and other support facilities. The site is the heritage-protected historic limestone Warden’s Court and Post Office building in the heart of Kalgoorlie’s heritage precinct. This brief presented a range of challenges, which many considered insurmountable.

Design challenges

Major design issues centred on:

- The physical and cultural constraints of fitting the highly complex programmatic and technological requirements of a contemporary courthouse into a nineteenth-century building.

- The constrained nature of the highly urban site.

- Cultural sensitivity to the diverse needs of Kalgoorlie’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations and court users, who are often from strongly traditionally oriented communities and outstations.

A culture-based approach

In Western Australia, 42 percent of the adult prison population is Aboriginal and 70 percent of the youth detention system is Aboriginal. Yet in the community, only 3 percent of the total population is Indigenous. Social scientists and criminologists continue to debate the reasons for these disproportionate rates of over-representation. However, most agree that at least part of the reason is that Aboriginal Australia has suffered, and continues to suffer, a high degree of cultural loss, with attendant disintegration of social structures, stability and identity. Further, enduring and wide-ranging cultural disconnections with mainstream Australian society contribute to both social and economic marginalization.

Given these facts, it is not too much of a stretch to suggest that part of the solution lies in an acknowledgment of – and engagement with – Aboriginal culture. As an architect, this line of reasoning brings us to two questions. Firstly, is culture relevant to justice delivery? Secondly, can architecture help?

It is not within the scope of this brief article to offer any fair synopsis of the depth, subtlety and majesty of an 80,000-year-old continuous culture, nor can we infer that Aboriginal culture could be so “bottled”. Yet those of us who have devoted years to working in traditional communities, and who have done so with respect and an appetite to learn, can claim an awareness of the range and subtlety of factors that are critical to our work as architects.

As a start, we can point to the importance of listening. We appreciate the profound and pervasive significance of Aboriginal connection to the land and more particularly to “country”. (The Western Desert word is Ngurra and refers to the actual “country” of a person’s origin and belonging and includes not only geographic but economic, emotional, obligatory, metaphysical and spiritual ties.) Most importantly of all we become aware of the importance of kinship and relationships. We learn how every occupant of the spaces we design will be obliged to behave in relation to every other person in that room according to a mutually understood and sophisticated web of kinship law and behaviour. This includes relationships of mutual obligation as well as some specific “avoidance” relationships. Aboriginal culture seems to have included an understanding of particular relationships that may be prone to tensions and are pre-emptively restricted by injunctions on contact. The most common of these is the relationship between son-in-law and mother-in-law. There are numerous instances of our courts system causing conflict in Aboriginal society, for example by unwittingly imposing upon a woman the necessity to testify as a witness in a case concerning a son-in-law. Even the matter of people (of a kinship type governed by avoidance relationships) having to sit in close proximity in waiting rooms will at the very least cause distress, if not trigger actual punishment under customary law to be reckoned with when they return to their respective communities.

Other cultural factors include language and the ways in which communication in the courtroom space may be hampered, if not disrupted, by inappropriate spatial solutions. English is a second – if not third – language for many Aboriginal people from the Western Desert Lands, and both witness stand and dock may need additional space for one if not two translators.

Personal space and acceptable distances between people of differing kin can affect non-verbal communication cues, including eye contact and sign language. This has a direct implication for space planning. Other factors include customary gender-specific injunctions on areas of the law.

And finally the whole area of art – the multidimensional meanings of form and visual language in architecture – cannot be successfully conceived without close collaboration with the Aboriginal people who are to be the users of our conceptions.

Inside-out architecture

Sensitivity and a spirit of collaboration were our aims for the Kalgoorlie Courthouse from the outset. At its heart, the design has inverted usual architectural thinking by making the outdoor spaces the central organizing principle of the whole project. In making these outdoor spaces work appropriately and comfortably for traditionally oriented Aboriginal people (as well as for the non-Aboriginal Kalgoorlie population), the built elements have derived their form and qualities.

The scheme is organized around a central linear landscaped courtyard spine. On one side is the historic Hannan Street building and on the other side the proposed new single-storey building. The courtyard elevation of the new building will be fully glazed, with large folding wall panels. These will enable both the public domain and the courtrooms themselves to dissolve into landscaped outdoor areas.

The complete separation of the old and new buildings allows the greater part of the generous outdoor domain to be situated entirely within a secure zone, defined by and contained within the two parallel wings of the complex.

A landscaped arrival forecourt, outside the secure zone, provides a central point from which both wings of the complex may be appreciated and accessed. This forecourt is situated at one side of the site and set well back from the street line of Hannan Street. Its 90-degree reorientation to the point of arrival enables large family groups – which often include young children – to arrive and wait in safety and privacy, discreetly away from the commercial street. It also gives access from two directions: both from busy Hannan Street and from a well-used laneway to the rear of the site.

The design also locates specific functions, for example the registry, on the Hannan Street frontage to activate the street and ensure a civic relationship between the building and the city it serves.

Ceremony versus accessibility

The higher courts – the more traditional and ceremonial jury courts – are located in the old building, taking advantage of its existing grand internal spaces and civic architecture. The new building will house the busier and more accessible magistrates’ courts. All three magistrates’ courts are at ground level, directly accessible from the secure landscaped central courtyard. This allows the large number of people and their supporting families to wait immediately outside their scheduled courtroom, either in the enclosed public waiting area or in the fresh air (the general preference). The direct proximity of an outdoor waiting area to each court means that people scheduled to appear may be easily found and called when their turn comes up. It is also intended to avoid the need for names to be called over public address systems, as the direct use of individuals’ names is still widely avoided in traditional Aboriginal culture (except where specific close kinship ties permit such intimacy).

Each magistrates’ court also has its own private courtyard exclusively associated with that courtroom, allowing proceedings to take place with direct access to fresh air, light and visual connection to native bush gardens. This is achieved without compromising the privacy and integrity of the hearings.

One of the magistrates’ courtrooms has been designed to permit maximum flexibility in its modes of operation. The usual tables for legal counsel have been replaced with a single elliptical table. This serves perfectly well for legal counsel during a usual court, but can also transform into a conferencing table for mediation and for the innovative Aboriginal Court procedure (called the “Community Court” in Western Australia). The Aboriginal Court was instigated in Kalgoorlie two years ago by pioneering magistrate Dr Kate Auty, who spearheaded this movement initially in Shepparton, Victoria in 2002. This latest innovation follows the success of similar programs in South Australia and Victoria (as well as the circle sentencing courts of New South Wales and Queensland). The special Indigenous Sentencing Courts have emerged in the context of other new “therapeutic” or “problem solving” court formats such as the Drug Court, which seek to identify underlying causes and, on occasion, implement programs of rehabilitation where a custodial sentence may not ultimately be most helpful. The Community (Aboriginal) Court has a courtyard sufficiently large to allow proceedings to take place out in the garden if appropriate.

Aboriginal collaboration in the design process

Extensive consultation with the local Aboriginal reference group continued throughout schematic design and design development – canvassing, testing and retesting a range of design solutions to cultural questions and paradoxes. Alternative access routes both onto and throughout the site allow for traditional respectful Aboriginal kinship avoidance behaviour. Alternative access routes also facilitate self-management of occasional hostilities between parties. Clear visual surveillance of one’s social and natural environment is designed into – and throughout – the entire complex. Anthropological research and analysis determined the actual distances required for cultural behaviours to ensure that the spaces work when large numbers of users and their families and supporters have to wait around or occupy the complex for long periods of time.

One of the Aboriginal lawyers of the Aboriginal Legal Service at Kalgoorlie approached us several times to ask that we design an outdoor space in a location that would permit the accused to have a cigarette shortly before appearing before the magistrate: “Clients are generally worried about going to jail and are stressed out and/or agro; in this state they can’t listen effectively when in court. So the ability to have a smoke is needed – can you allow a space near the court’s holding cell?”

If we listen to what we are being told in such consultations, we start to find the answers to the challenge: How can architecture be compassionate? So we included two small landscaped courtyards, each attached to a holding cell immediately outside the magistrates’ courtrooms. These provide visual relief and a calming outlook, fresh air and the opportunity for a smoke just before appearing before the magistrate.

Circulation

The near impossible circulation requirements of the contemporary courthouse, with five fully independent circulation systems – never crossing – has been fully achieved within the constraints imposed by the old building and its extension. The leading role that Aboriginal Elders play in the judicial process is acknowledged and formally celebrated, with an Elders’ meeting room associated with the community court directly off the judicial circulation route.

Heritage

New construction is generally kept entirely discrete from the original building. This approach will enable the building to be completely restored to its original condition without offending extensions and accretions, and allow the handsome structure to be appreciated “in the round”, as its original designers had intended.

Environmentally sustainable design

Opening up the public domain to the landscaped courtyards, in combination with zoned airconditioning, makes it possible to naturally ventilate the entire public domain, saving on airconditioning for a large proportion of the year. The courtrooms may also be fully opened up and airconditioning shut down. An underground labyrinth pre-cools ambient air, thereby decreasing the size of the aircon plant and the amount of energy needed to run it.

Philip Kirke is a senior associate at Hassell. He is the project architect for the Kalgoorlie Courts Project.

KALGOORLIE COURTS PROJECT

Architect

Hassell in collaboration with Professor Graham Brawn, Lin Kilpatrick Architect and Kevin Palassis Architects—project principal Caroline Diesner project architect Philip Kirke design architects Caroline Diesner, Philip Kirke, Martin Dutry, Graham Brawn. project team Davina Allen, Andrew Koniuszko, Dirk Collins, Colin Dibb, Caesar D’Adamo, Lyle Henri, Anna Fairbank.

Service, structural, civil and fire engineer

Aurecon.

Quantity surveyor

Davis Langdon.

Landscape architect

Plan E.

Acoustics

Gabriels Environmental Design.

Hydraulics

Hutchinson Associates.

BCA consultant

John Massey Group.

Security

SKM.

Client

WA Dept of the Attorney General and WA Dept Treasury and Finance (Building Management and Works).