It rained the day of my first visit to Killara House, so the creek – usually a trickle – was a torrent. The house has been compared over the years to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, but Penelope Seidler begs to differ. “Having visited Fallingwater in the 1980s, I take that as a huge compliment; however, it’s quite different – built beside a creek, not over a waterfall. But the big hovering plane of the balcony … the horizontal lines, there are similarities, I suppose. I think the site demands them.”

The wife of the late Harry Seidler is an architect in her own right, CEO of the Seidler practice and a patron of the arts. She has lived in the Killara House for more than forty-four years and, with Harry, raised their children, Timothy and Polly, here.

Killara House is not only a part of their family history, it has a place in Australia’s architectural story as well. Harry Seidler came to Australia in 1948 at the age of twenty-five, an architecture graduate with engineering credentials. He had studied architecture at Canada’s university of Manitoba and did his postgraduate degree at Harvard, studying with Walter Gropius, Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer, with whom he later worked in New York. En route to Australia in 1948, he stopped in Brazil and worked briefly with Oscar Niemeyer in Rio de Janeiro. He brought with him not only the Modernism of his Bauhaus émigré teachers, but also the broad world view of an outsider.

His first house in Australia was designed for his parents. The 1948–1950 Rose Seidler House in Wahroonga is a delicate timber home that today is a much-loved museum for the Historic Houses Trust. “Harry had just come from America and that’s how he’d build things with Marcel Breuer; it’s very much a North American house,” says Penelope.

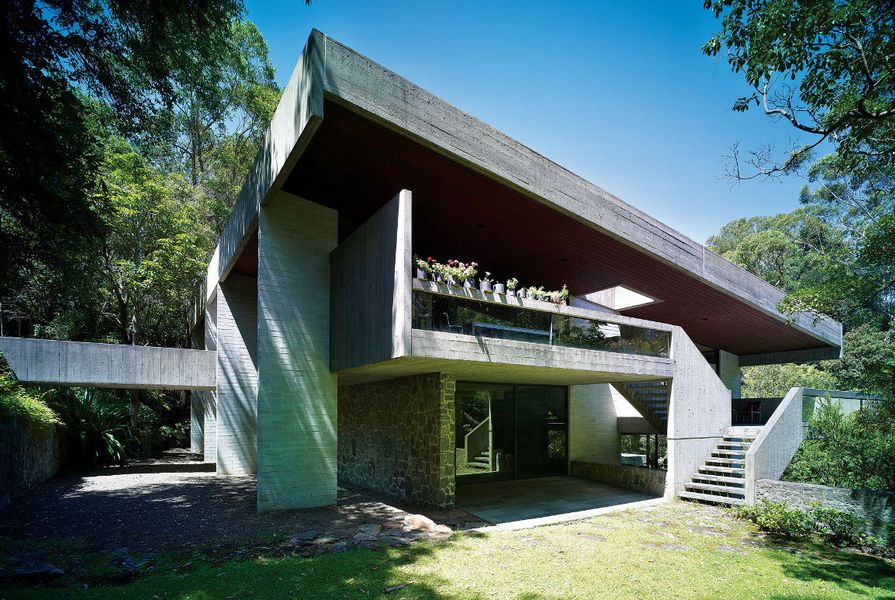

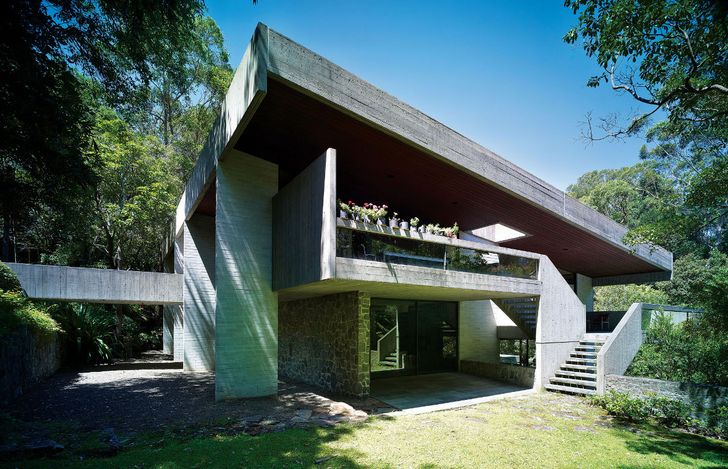

Within a decade his ideas had developed in a different direction, becoming more attuned to the Australian climate and focused on a connection to the outdoors. He began exploring concrete construction for its flexibility and thermal mass, and discussed his (still influential) ideas in the 1954 essay “Our Heritage of Modern Building.” Killara House embodied much of this new thinking, with a new typology for suburbia.

Harry and Penelope designed the house together. They had met in 1957 and married in 1958, after which she enrolled in architecture at Sydney University. From 1960 they lived at the recently finished Ithaca Gardens Apartments in Elizabeth Bay while looking for land, till they found the Killara site.

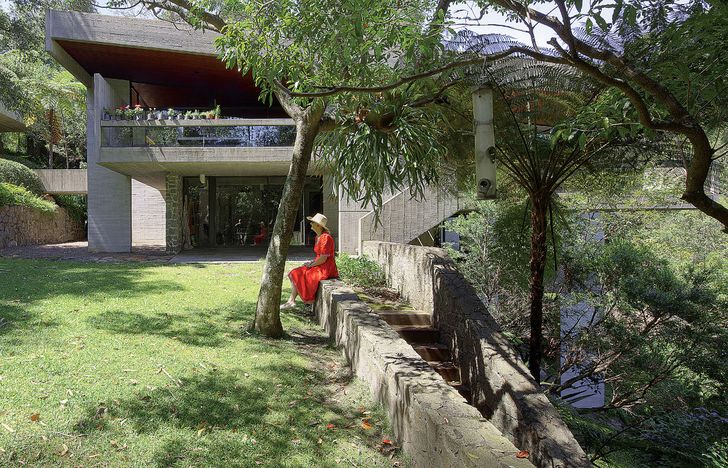

Penelope Seidler enjoys the loosely landscaped bush block, lush with native plants.

Image: Brett Boardman

“It was what you’d call an architect’s block: steeply sloping, surrounded by trees, a creek at one end, a bush reserve at another, and no immediate neighbours. It was just what we wanted,” says Penelope. It took two years before the owner would sell to them, and another eighteen months to build the house.

“Harry came up with the plan almost immediately. I had input and made some modifications, but my role was really one of the enlightened client, if you like. If I’d designed the house myself, it would have been very different … probably not as good. Everywhere you go you experience the outdoors and the trees, which is what I’ve loved the most about living here.”

The Killara House was an exploration in concrete construction, playing with its flexibility and thermal mass.

Image: Brett Boardman

The house has a split plan over four half-levels, which organizes the internal functions and helps fit the building into the sloping site. Communal daytime areas – dining, living and sitting rooms, kitchen and children’s playroom – all face north, while the bedrooms, utility areas, bathrooms and Harry’s study face the quiet south side.

A suspended concrete entry bridge leads to the top level, where the dining room and galley kitchen open to a long cantilevered terrace. Down a half-flight of stairs the living area faces north and west, directly into a canopy of eucalypts. Also on this level, the west-facing master bedroom has an east-facing clerestory window to permit morning light, another trick of the levels.

Downstairs, the children’s playroom opens directly to the north garden, while three bedrooms facing south and east look into shaded pockets of garden under the entry bridge. The lowest level houses a guest suite (south) and a second studio, in the north-west corner, where Harry would go to build models uninterrupted.

A suspended concrete entry bridge leads to the top level.

Image: Brett Boardman

Each half-level offers glimpses through and beyond to the next level and out to the garden. Loosely landscaped, the bush block is lush with flowering ginger running along the contour lines to the creek. Flagstone paths cut around rock, through native ferns and grasses to the swimming pool. This was added in the 1970s for the children, and Penelope still enjoys her morning swim.

The material palette is machined, yet visceral, expressing the structure of the house. The concrete block support pillars are left exposed, along with concrete walls, embossed with the timber grain of their formwork, wrapping from outside to in. Floors are a wet-looking quartzite stone, ceilings a light Tasmanian oak. Cutting through the levels is a monumental fireplace of local bluestone, around which all the public areas are organized.

In section, the house is a series of half-levels that offer glimpses through and beyond the adjoining levels.

Image: Brett Boardman

Seidler was a passionate advocate in the design debates that shaped postwar Sydney. He was also a keen observer through photography and the thousands of images taken for his Taschen tome, The Grand Tour: Travelling the World with an Architect’s Eye, are still archived in his study, which is just as he left it.

Also untouched (except for dusting) are the shelves of mini architectural models the couple collected from iconic buildings they visited together, and their collection of art, the only thing Harry and Penelope disagreed on. “Not so much in the early days, but I became more involved in art and went on several trips into the interior and the Kimberley and Arnhem Land and bought quite a lot of Aboriginal art. It was just off Harry’s radar, I think. It didn’t fit his total concept. For a long time I used to buy things and hide them in cupboards. But once he got used to it, it was alright.”

“Harry would argue, and I would too, that in all the great buildings anywhere, art – the major pieces – is part of the building. It all goes together, it’s not just a capricious thing you change every five minutes.” The family furniture has similar status: tables and chairs by Breuer and Eero Saarinen, and all the rugs and hides originally bought for the house still there today. “I guess we got the design right the first time and we’ve done very little since, except for routine maintenance.”

They moved into the house in 1967, the year Australia Square was finished. It was the country’s first real concrete skyscraper and it put Harry (and engineer Pier Luigi Nervi) on the world stage, winning the Sir John Sulman Award for Public Architecture (and the Civic Design Award, for the plaza) from the Australian Institute of Architects, while Killara House won the Wilkinson Award.

Forty years later, Harry was again doubly honoured. The Institute established the Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture in 2007 and the bushland beside Killara House was renamed Harry Seidler Reserve. Today the house is on the NSW State Heritage Register and is becoming a pop culture icon, with more and more requests to do photo shoots here.

“Funnily enough I find people like the house a lot better now than they did when it was first built. They thought it was all too stark and found the concrete too confronting. I think it’s beautiful. There’s a medieval quality to the masonry walls, and the texture of timber all around, it’s like my castle. Harry liked things tough; he always said this house was indestructible, and he’s absolutely right.”

This review of the Killara House is part of the Houses magazine Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- Killara House by Seidler

- Architect

- Harry Seidler

- Architect

-

Harry Seidler and Associates

- Project Team

- Penelope Seidler

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 1 Oct 2011

Words:

Peter Salhani

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Houses, August 2011