From Southern Highland retreats to Mornington weekenders, the history of Australian domestic architecture is as much a history of the holiday home as it is a history of the suburban house. Dwellings in remote bushland settings that speak of some ecological consciousness have become an accepted symbol of Australian architecture abroad, yet rarely are their environmental values or pioneering rhetoric placed under historical scrutiny. Rather than concentrate on high architecture for a wealthy elite, I am most interested in designs that made holidays affordable, particularly for people who live outside of cities. In contrast to their European counterparts, Australian social reformers in the early part of the twentieth century focused more of their efforts on improving the welfare of a rural rather than urban population through the promotion of bush nursing schemes and cheap seaside homes. Pioneers were both mythologized and pitied and, unlike in the United States and its West, the settlement of the frontier was still an ongoing political project in northern Australia.

This was not simply about taming the land for economic reasons but an aggressive assertion of White Australia, where fears of Asian invasion were regularly stoked in the popular press. In the face of global population pressures, settlement was not only politicized but also racialized, as Alison Bashford argues in “World Population and Australian Land” (2007). Populating northern lands was seen by Melbourne’s federal politicians as an imperative to maintain Australian sovereignty of the whole continent. But medical opinion was divided about what the long-term health effects would be. Nowhere in the world were White anxieties about race, place and health more pronounced than in northern Queensland in the decades spanning from 1900 to 1930. Climate was thought to affect intelligence, fertility and mental health, with many local doctors fearing the progressive degeneration of pioneering families unless they could protect themselves from the heat and humidity.

In addition, bats, rats and mosquitoes were all newly recognized threats to health. While tropical medicine was confident that conserving health was largely a matter of disease control, reformers still promoted the benefits of environmental cures, particularly for women and children. Trapped in hot, dusty, tin homes, women and children were considered most at risk from the ill effects of climate. The trouble was that holidays cost money and were out of reach for most poor settlers.

Innovative for their time, the huts’ kitchens featured flip-down tables, enamelled sinks and linoleum floors.

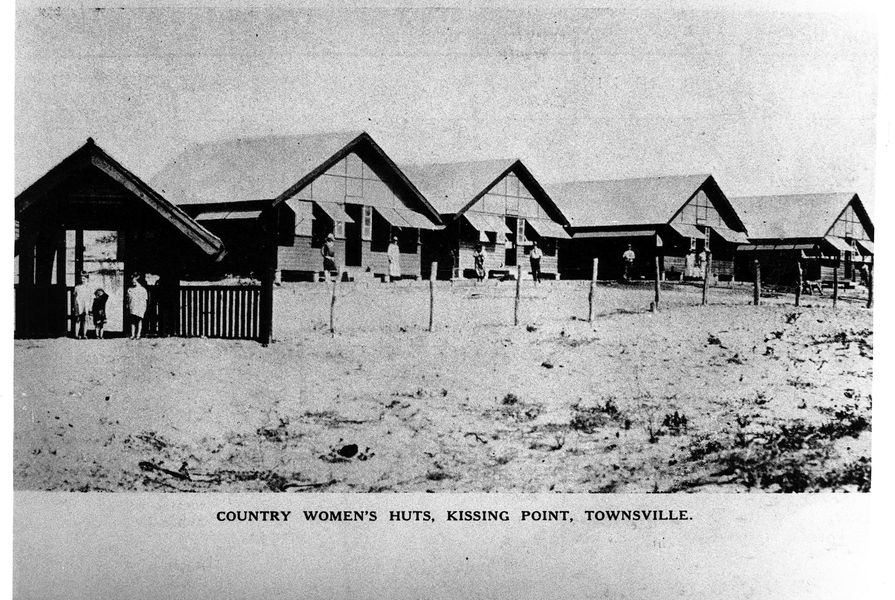

So what architectural projects emerged from this maelstrom of tropical paranoia and social concern? The most innovative and radical proposal was made in 1924 by the Townsville architect C. D. Lynch for holiday homes at Kissing Point. Developed for the Queensland Country Women’s Association (QCWA) on state-gazetted land, Lynch’s beachside proposal allowed the country women of northern Queensland to have a change of scene for a nominal sum. The initial layout showed seven self-contained wooden huts, staggered around an octagonal summerhouse with shared laundries at the back of the site. Local branches of the QCWA banded together to fund each individual hut and in exchange their members could have an affordable vacation. Construction costs had to be kept to a minimum to make fundraising more effective and it was Lynch’s ability to reduce the house to its bare essentials that produced quite startling results.

A roving country practitioner, whose offices in Townsville, Ayr, Cloncurry and Cairns covered the main population centres in the Far North, Lynch was more celebrated in medical circles than in architectural ones. Not afraid to challenge conventional wisdom on environmental design, he rejected the prevailing belief that the external verandah was “the panacea for all tropical house troubles” (as he wrote in the Townsville Daily Bulletin in 1920). In 1919, he produced a design for a double-brick residence for the Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine (AITM) that dispensed with external awnings in favour of a cross-shaped breezeway. Yet despite the interest of the medical press in Australia and India, Lynch struggled to find domestic projects for his unconventional ideas.

Designed in 1924 by C. D. Lynch for the Queensland Country Women’s Association, the Kissing Point Huts served as a low-cost holiday retreat for QCWA members.

Image: Courtesy of City Libraries Townsville, Local History Collection.

The QCWA may today seem an unlikely choice for experimental architecture, but in 1924 it was a newly formed association with an expanding membership, well supported by the political establishment and with close links to the AITM in Townsville. Lynch was brought in as honorary architect to the northern branches of the QCWA and found in them a client willing to try new ideas about kitchen design, house layouts, and building in the tropics.

The plan of each holiday home was reduced to a single large room, roughly eight metres by seven metres, with dressing areas and galley kitchen screened from the main living area, which doubled as a bedroom at night. The building was raised on timber stumps, clad in weatherboard, without any internal lining. The eaves of the high pitch roof extended well over the walls, with the gaps between the joists left open to allow ventilation. In keeping with his principles, Lynch dispensed with the verandah for each timber-framed weatherboard hut. Instead he provided adjustable top-hung shutters to shade the interior and facilitate cross-ventilation. Although Beni Burdett resolved this more elegantly in his Commonwealth housing in Darwin, Lynch’s work precedes it by more than a decade.

However, it was the kitchenette that attracted most attention in the press. Visitors gushed about the enamel sink, flip-down tables and ironing board, enamel and gas stove and the linoleum floor. This is unsurprising as few of the members’ homes were so well equipped or serviced, with many coming from homes with just a single tap in the yard. Yet Lynch’s kitchen also addressed the concerns of doctors such as Raphael Cilento at the AITM. The kitchen was the hottest room in the house and the place where women were seen to be most at risk of neurasthenia and heat exhaustion. Cilento was convinced that better planned kitchens, saving time and effort, were a physiological necessity in northern Australia. He advised Commonwealth and state architects but Lynch’s plans went far beyond the efforts of any of them in the attention he paid to space-saving joinery and labour-saving devices.

Hut by hut, the Kissing Point holiday homes expanded from one building to six between 1924 and 1937, including a caretaker’s cottage complete with a memorial room celebrating the achievements of Pioneer Women of Queensland. Another cottage was built in Bowen along similar lines and today is the only hut remaining from Lynch’s initial design. Between the 1960s and early 1980s the Kissing Point huts were gradually replaced by walk-up apartments. Members would no longer tolerate the makeshift bedrooms or outside toilets. When the first hut at Kissing Point opened, the Governor-General pointed out its importance as a first step in alleviating the conditions of rural women and children. Populating the remote parts of Australia was seen as the patriotic duty of White Australians. As a tangible benefit for members and an early focus for fundraising, the QCWA’s holiday homes created not just a cheap place to take a break, but a model for citizenship where communities, along the coast and in the interior, banded together to improve civic facilities. They also allowed local architects, like C. D. Lynch, to trial approaches to tropical architecture that private clients were reluctant to support. Yet the homes also solved a political dilemma – how to make tropical living more attractive, not just to promote settlement but to stop those already there from leaving.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Sep 2015

Words:

Daniel Ryan

Images:

Courtesy of City Libraries Townsville, Local History Collection.

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2015