The manipulation or appropriation of landscape has historically been used as a powerful device for representing human ideologies and values. As I discovered, Kosciuszko is a name synonymous with the contested landscapes of two countries – one a naturally formed mountain peak revered for its grandeur and rugged beauty, and the other a human-made memorial peak steeped in the history of a nation. United in name and spirit, they express the ideals of democracy and liberty.

My personal interest in the name Kosciuszko began while attending the Topos conference in Krakow, Poland in 2010 when Marcin Gajda of Polish landscape firm AKG Architektura Krajobrazu took me to view the Kopiec Kościuszki (Kosciuszko Mound). Surprised to discover an engineered landscape edifice that bore the same name as Australia’s tallest mountain, I took an interest. So began a journey that was concluded last year upon stumbling across a bronze monument in Detroit to the same man, Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

The name of Australia’s highest mountain, Mount Kosciuszko, is at odds with the English and Aboriginal names scattered across the Australian map and most people are unaware of its origin. In 1840 Polish geologist and explorer Paul Edmund de Strzelecki renamed the mountain in honour of the pursuit of the ideals of democracy, a quiet hope for the fledgling European nation. In Poland, an engineered mound in Krakow also bears the name Kosciuszko. Again, it symbolizes hope for a free future and expresses gratitude to one man, Tadeusz Kosciuszko, for his lifelong fight for that ideal.

Mount Kosciuszko. In 1840 Polish geologist and explorer Paul Edmund de Strzelecki renamed the mountain Kosciuszko in honour of the ideals of democracy.

Image: Tony Brown

The link between these two landscapes is something few Australians or Poles are likely to be aware of. The story of the name of Australia’s highest mountain and of a memorial mound in Poland stems back to 1746 with the birth of Tadeusz Kosciuszko in Mereczowszczyzna, Poland.

Born during a time when political tensions were rising in Europe over Polish territory, Kosciuszko dedicated his life to military strategy and to fighting for his personal ideals of freedom, independence and equality. These ideals were embedded in him at an early age and reflected the prevailing attitudes and philosophies of intellectuals across Europe during the Enlightenment period. A cultural movement beginning in the late seventeenth century and led by intellectuals such as Francis Bacon, Voltaire, René Descartes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Age of Enlightenment emphasized reason and individualism rather than tradition and superstition.

At age nineteen, while studying at the Corps of Cadets in Warsaw where he was trained in accordance with the “Enlightenment program,” Kosciuszko began to show talent in many subjects. Later, when he went to France to study at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, he was heavily influenced by the Enlightenment atmosphere of Paris and he developed his own philosophy on the importance of individual freedom. His talents allowed him to become skilled in a variety of disciplines and he studied military and civil architecture, artillery, military strategy, economics, art, drawing and painting. It could be said that his beautiful drawings and fortification designs are the mark of a great landscape architect.

In 1772, while Kosciuszko was studying in France, Poland experienced what is known as the First Partition. The country was forced to defend its territories against invasion by Prussia, Russia and Austria, only to be defeated and to lose significant portions of its territory to the three powers. In total, one quarter of Poland’s territory was lost. Kosciuszko returned home to Poland in 1774 seeking work but soon left for America to volunteer to join in America’s fight for independence from the rule of Great Britain.

There he was hired by Benjamin Franklin, an influential intellectual, statesman and politician during the American Enlightenment. After Kosciuszko proved his skill as a military engineer, Franklin allowed him to work for the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, putting him in charge of designing forts to protect Philadelphia from the British Royal Navy.

Kosciuszko soon began to make his mark both on the American landscape and on the outcome of America’s fight for independence. His participation in the American War of Independence was vital as he established strongholds such as that of West Point, where he designed fortifications and battle plans that allowed the American colonies to gain advantage over the British Army. He was awarded the rank of brigadier general for his contribution.

During the War of Independence Kosciuszko made many friends in America, including two of its future presidents, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. He strongly influenced the values of these two men, encouraging the education of slaves and peasants and supporting the plight of the oppressed. These friends later made important contributions to American history during their presidencies.

In 1784, after the American colonies defeated Britain in 1783, Kosciuszko returned to Poland to spend time farming at his family’s estate in Siechnowicze. While at home he became politically active and held strong opinions on creating a free Polish state and reigniting the Polish spirit. He helped to re-establish the Polish army, which had been significantly depleted by the First Partition, and led the country to the adoption of a new constitution called the Constitution of May 3, 1791, which created renewed hope and nationalism for the Polish people. Their attempts to regain their territory led to the Second Partition, when they lost two thirds of their territory to Russia and Prussia.

Despite this defeat, the Polish people still regarded Kosciuszko as a freedom fighter and saw his efforts as heroic. In response to the Second Partition Kosciuszko led another uprising and won support from a large number of people, including the Polish Jewish community, which until then had been operating as a separate community from the non-Jewish Poles. According to Alex Storozyński in The Peasant Prince Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution , Kosciuszko requested the participation of the Jewish community in the uprising, in return promising them equality in Polish society. As a result, the Jewish community formed its own cavalry, the first since biblical times, and provided strong support in the Polish uprising against Russian occupation.

Kosciuszko managed to form an unexpectedly strong opposition to the Russian army and Poland gained some significant victories. But he was defeated in Maciejowice and was captured by the Russians and imprisoned in Russia. He was released in 1796 but banished from Poland.

In spite of the complete abolishment of the Polish state in the Third Partition, Polish people remained loyal to the Constitution of May 3, 1791 and continued to hope for a free Poland. On his release from prison, Kosciuszko travelled across Europe to England before returning to Philadelphia in the United States. He stayed for less than one year and before his departure in 1798, he wrote a will leaving his estate to Thomas Jefferson, asking for the funds to be used to free Jefferson’s slaves and to educate them. He returned to Europe and continued his fight to restore Poland until his death in Switzerland in 1817.

Today there are monuments to Kosciuszko in a number of American cities, recognizing his role in the country’s fight for independence as a hero and patriot of the American Revolution. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, his former home has been preserved as a national monument.

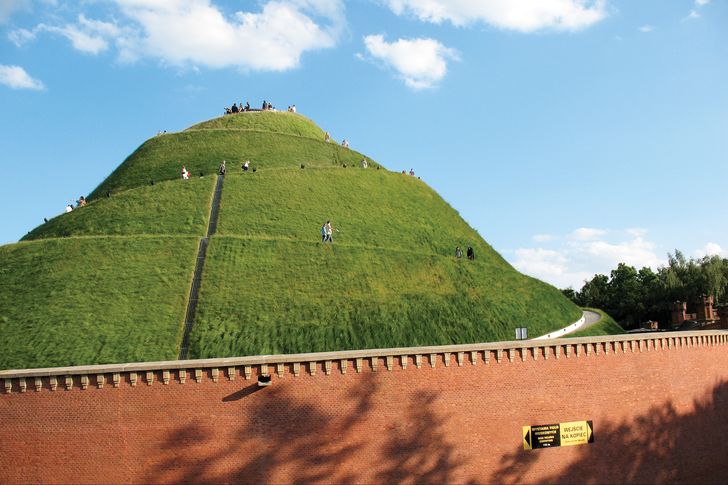

The Kosciuszko Mound in Krakow, Poland, was constructed between 1820 and 1823 as a memorial to Tadeusz Kosciuszko, a Polish national hero.

Image: Ric Glassey

The Kosciuszko Mound – a symbol of independence and liberty

The human-made mound in Krakow is the most recognizable link to Kosciuszko and is a profound landscape symbol for the Polish people. Built while the city of Krakow was experiencing a brief period of freedom, the Kosciuszko Mound was constructed as a memorial to Tadeusz Kosciuszko. Between 1820 and 1823 Polish workers travelled from all over Poland, most of which was still under foreign occupation, to be part of the construction of the mound. Soil was brought from the battlefields where Kosciuszko fought to contribute to the memorial. The official website for the Kosciuszko Mound describes its symbolic importance:

“The Committee’s intention was to set up a peasant settlement at the foot of the Leader’s Mound, called Kościuszko. The settlement was meant to be inhabited by the veterans of the Insurrection and their offspring, who would be farming the parcels of land granted to them. This idea, intended to be a symbolic implementation of the social testament of Kościuszko, was not possible to be achieved fully.”

Mounds, both as burial sites and as strategic structures, are an important part of the Eastern European landscape, as they are in many parts of the world. As a symbolic tomb, the Kosciuszko Mound was built of native soil and stones, like the prehistoric Cracovian mounds of Krak and Wanda, named after the founder of Krakow and his daughter.

The construction of the Kosciuszko Mound was completed in 1823 and a committee appointed to safeguard its future. The committee, today known as the Committee of the Kościuszko Mound, has protected the structure ever since, through periods of war and foreign occupation. During the Austrian occupation of Krakow, the Austrians decided to erect a large stronghold around the mound, one in a series of such fortifications in Krakow. The fortifications around the Kosciuszko Mound, designed by military architects including August Caboga, were built between 1850 and 1854 and were in the shape of a citadel with neo-Gothic and neo-Renaissance elements.

The Kosciuszko Mound deteriorated over the following century but was finally restored between 1999 and 2003. This involved removing approximately nine metres of soil and reconstructing using geo-technology to ensure that the mound would withstand landslides and future weather events. The plaque commemorating the restoration of the Kosciuszko Mound sums up its symbolic significance, saying it “has been restored as an everlasting sign of the independence of Poland and solidarity between nations in the name of welfare of humankind.”

The Australian connection

The man responsible for the naming of Mount Kosciuszko in Australia, Paul Edmund de Strzelecki, was born at the end of Kosciuszko’s life in 1797 near Poznan in Poland. Strzelecki was educated in Poland but did not finish his education, instead leaving school to serve in the Prussian army before travelling in Europe. He returned briefly to Poland but then travelled in England, North America, South America, the Pacific Islands and Australia, analysing soils and minerals. During these expeditions he was exposed to slavery in South America and came to feel the same distaste for it as Kosciuszko.

Strzelecki’s work in Australia included conducting a geological survey that allowed him to explore areas in Australia not yet covered by Europeans. As did Kosciuszko, Strzelecki held a strong respect for indigenous people, especially for Aboriginal Australians. His high regard for the skills of Aboriginal people led him to have two Aboriginal guides on his ascent of the highest peak in Australia. On arrival at the summit, Strzelecki named the peak Mount Kosciuszko out of respect for the Polish freedom fighter and also to express the importance of democracy, freedom and equality amongst people. Ironically the mountain’s Aboriginal name Jagungal was extinguished in the process.

Today, these two peaks, one in Poland and the other in Australia, lie on the contested soils of two nations, serving as symbols to a set of ideals common to both. To some they stand as a testament to democracy, but to others they represent wrongful appropriation. If Australians aspire to uphold the spirit of Kosciuszko, the time will come when, through meaningful reconciliation, a nation will be ready to return Jagungal to its people.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 30 Apr 2015

Words:

Adrian McGregor

Images:

Ric Glassey,

Tony Brown

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2015