THE OCCUPATION OF LAND, BOTH SYMBOLIC AND PHYSICAL, IS A HIGHLY POLITICIZED ACTIVITY, AND NOWHERE MORE SO THAN CANBERRA. CHRISTOPHER VERNON CONSIDERS TWO NEW LANDSCAPE PROJECTS IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL.

The glass mosaic on the bottom of the Suffrage Fountain

Overview of the Suffrage Fountain. Located in the House of Representatives Garden, the fountain is aligned on one of the garden’s original axes. Photographs courtesy of the National Capital Authority. We are unable to illustrate Jennifer Turpin and Michaelie Crawford’s competition-winning Fan, as the Federal Government would not release an image. However, it can be seen at www.women.gov.au/content/story.asp?story_id=2101

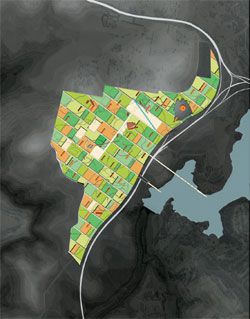

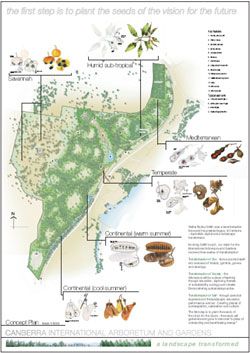

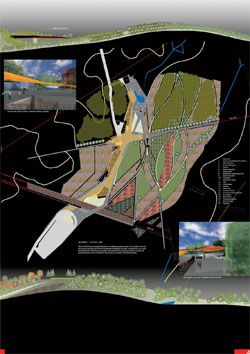

Shortlisted entry by Taylor Cullity Lethlean and Tonkin Zulaikha Greer.

Shortlisted entry by Anton James Design.

Shortlisted entry by Clouston Associates Landscape Architects.

Shortlisted entry by Jones Sonter Architecture and Urbanism.

Shortlisted entry by Inspiring Place.

Entry by Gresley Abas Architects and Peter Jones Architect, one of five entries to receive a Certificate of Commendation. Other commendations went to Billard Leece Partnership, Oculus Melbourne, Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture, and Tony Edye & Associates.

IN CANBERRA, THE civic grandeur associated with national capitals emanates not from concentrations of monumental architecture, but from the city’s landscape setting. Two new design initiatives reinforce the distinctive pre-eminence of the capital’s landscape, suffusing the deceptively “natural” with a more explicitly constructed dimension. The first is a public artwork commemorating the Centenary of Women’s Suffrage. The second is for the new Canberra International Arboretum and Gardens. Together these projects manifest Canberra’s dual governance – the suffrage artwork was a Commonwealth collaboration between the Office for the Status of Women and the National Capital Authority (NCA). The arboretum is an Australian Capital Territory Government initiative.

The actual and symbolic occupation of land is a politicized and often contested activity. This is even more acute at the national capital. Here, development of prominent sites, especially those on the Griffins’ Land Axis, cannot be anything but politically charged. The initiative to commemorate women’s suffrage became fraught with controversy quickly after it began and a survey of this two-year episode and its compromised outcome emphatically underscores my point. With its proposed arboretum, the ACT Government – unusually, not the Commonwealth – is poised to realize an important component of the Griffins’ original Canberra design.

In June 2002, Senator Amanda Vanstone, then Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for the Status of Women, launched a design competition for a public artwork celebrating the “Centenary of Women’s Suffrage”. Although the motivation for the genre remains unclear, from its outset the project was conceptualized as a “public artwork”, not a memorial. That December, the submission by Sydney artists Jennifer Turpin and Michaelie Crawford was announced as the winner. Turpin and Crawford’s work took the form of an “elevated semi-circular kinetic sculpture”, 21 metres in height. On still days, the red, fan-shaped steel sculpture “rests in an open fan position”; with wind, however, the individual blades (collectively spanning 24 metres) “move fluidly”. Site-specific in its scale, the “red fan” was to be positioned on the land axis between Old and New Parliament House. The jury unanimously agreed that the sculpture’s “monumental scale, rich colour and its ceaseless movement will make it a notable feature” of the axis.

Turpin and Crawford next developed their design in consultation with the NCA. For instance, reducing the artwork’s height from 21 to 18 metres. In August 2003, photographic montages of the sculpture in situ – albeit misrepresenting its scale – appeared in the media. Fuelled by these images, controversy surrounding the sculpture’s highly visible location on the heritage-listed Land Axis erupted. This protest was largely unanticipated as little concern was expressed at the time the winning design was announced and the site was long known. It had been specified in the competition brief, and already had approval from the Australian Heritage Commission and both Houses of Parliament. Nonetheless, controversy burgeoned and culminated the next month with the abandonment of the design. Sidestepping the issue of location, the Commonwealth maintained that the sculpture could not be completed on time or within budget.

In November 2003, Senator Kay Patterson (Vanstone’s ministerial successor) announced that a new artwork would take the form of a fountain and the site was predictably shifted. Abandoning the Land Axis, the Suffrage Fountain was now to be constructed at its periphery, within the House of Representatives Garden beside Old Parliament House. This was not the first time that the axis had repelled a commemorative object. In the 1960s, a monolithic statue of King George V was laterally shifted off-axis as it obscured the view to the War Memorial. Such manoeuvres suggest that the Land Axis is approaching sacred status.

The suffrage artwork’s locational shift was not without its own symbolism. Likening the new site to “the back paddock”, two Canberra Times readers surmised that “only male constructions are allowed” on the Land Axis. The new site, apart from its comparative invisibility, also has gender associations. The Suffrage Fountain would join the Ladies Rose Garden as a feature within the House of Representatives Garden. If the Land Axis is seen as “masculine” owing to its largely militaristic symbolic content, then the garden location is constructed as “feminine”. Moreover, by virtue of its new site, the suffrage project expediently dovetailed with the NCA’s parallel initiative to reconstruct the Old Parliament House gardens. A designed landscape of heritage significance, these gardens are a rare artefact within this youthful city. Unsurprisingly, the NCA’s decision to reconstruct rather than restore the gardens also attracted protest. Literally and metaphorically, the suffrage project’s identity would become subsumed by the garden reconstruction initiative.

Designed by the NCA, the Suffrage Fountain opened in December 2004. Positioned near the garden’s entry and framed by wisteria-clad pergolas, the white fountain is approximately 7 metres long by 2.5 metres wide by 0.4 metres high. A remarkable, finely crafted glass tile mosaic lines the rectangular basin. Its abstract design inspired by wisteria, the mosaic is executed in the suffragette shades of green, white and purple.Water jets provide variable displays, sound enlarging the visual experience. Likely a concession to the site’s heritage values, the Suffrage Fountain is stylistically compatible with the garden’s pergolas and other structures. Unfortunately, this concession came at the expense of the fountain’s own discrete identity. In turn, these wider surrounds imbue the project with an historicist atmosphere. This quality, however, is paradoxical; the fountain is, of course, a contemporary intervention and the garden effectively a replica. The visual and temporal dialogue between old and new is disturbingly ambiguous.

Otherwise an isolated object, the Suffrage Fountain appropriates its setting to give it a spatial dimension. The fountain is aligned on one of the original garden axes, an extension of Old Parliament House’s plan geometry. Historically, the axis spatially linked the Representatives Garden to the building’s internal courtyards and then extended to the Senate’s counterpart garden on the other side. Today, the axial view west across the fountain passes through the Members Gate and across an adjacent car park, only to be abruptly terminated by the wall of a later building addition. To the east, a new interpretative suffrage timeline inscribes the axis within the pavement.

Although pleasant enough as a garden ensemble, the Suffrage Fountain and its timeline are unconvincing in their role as a twenty-first-century commemorative artwork; the opportunity to interrogate the physical expression of commemorative ideals was missed. The national and, indeed, international significance of women’s suffrage demanded an innovative artwork on a highly visible site. It was awarded neither.

Every generation is entitled to give built expression to its values and achievements, and this means that the national capital’s commemorative landscape is always necessarily incomplete. The “red fan” tragedy cautions us that some wish to limit commemorative expression to a conventional language and confine its inscription to marginal sites.

When Old Parliament House opened in 1927, Canberra was already known as the Bush Capital, owing to its remote inland location. Today, the label alludes to the pervasiveness of actual bush within the city. Canberra’s “bush”, however, is a cultivated mosaic of remnant indigenous vegetation, street trees and parklands of native and exotic species and commercial timber plantations. Indeed, Canberra’s density owes more to vegetal architecture than to its built counterpart. Living in close proximity to this “bush”, however, is not without cost, as the bushfires of 2003 demonstrated. All of the bushfires’ consequences, however, were not tragic. Most prominently, the fires made an impact on the nation’s perception of its capital. To its detractors, Canberra is “artificial” and “un-Australian”. However, as few Australian cities are immune to bushfires, the tragedy made Canberra “real” in the national psyche – if only momentarily.

The ACT Government’s new initiative to construct the International Arboretum and Gardens is a more tangible, positive outcome of the otherwise devastating fires. Taking the first step toward its realization, Chief Minister John Stanhope launched a Design Ideas competition in September 2004. This was the first stage of the competitive process; in the second, the five finalists will resolve their initial concepts to a detailed level. The project’s considerable significance to the ACT Government is shown by its laudable decision to avoid expediency and to instead undertake a competition, and by its financial commitment of $10 million over three years (with $100,000 in prize money).

Arboretums have a long-established history, especially in North America. However, the term is relatively unfamiliar in Australia and the ACT Government defined “arboretum” as “a living museum where trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants are cultivated for scientific and educational purposes”. Enlarging this scope, the Canberra International Arboretum and Gardens are also envisaged as a recreational facility, a venue for large-scale events and a high-profile tourism destination. The competition brief required, for instance, a permanent bonsai exhibition, a visitors centre to accommodate meetings and exhibitions, a restaurant and function centre (which would also open at night), and extensive gardens, including areas for horticultural events. As well, the arboretum is to feature an outdoor concert venue with a capacity of at least 5,000 people and public art displays.

The project’s precedent is Walter Burley Griffin’s 1915 design proposal for a Continental Arboretum at the national capital. As the new arboretum is no less a landscape design proposition, the project begs attention be given Griffin’s lesser-known abilities as a landscape architect. In fact, the Canberra International Arboretum and Gardens site is mostly located within Griffin’s original arboretum precinct and contains relict plantings made under his direction. The new arboretum’s realization will, at the same time, mark the belated implementation of another component of the Griffins’ original city design. This is a national achievement for the local government.

The site is dramatic. Located near the western end of Lake Burley Griffin, the expansive, 250-hectare site extends from Griffin’s original cork oak plantation at the Glenloch Interchange in the north to the Molongo River in the south, taking in the Green Hills area alongside Tuggeranong Parkway and Dairy Farmers’ Hill. These local mounts, sacralized in the Griffins’ topographically driven Canberra design, provide remarkable panoramic views. Prior to the 2003 bushfires, much of the site was a commercial pine plantation (other portions burned in another fire in 2001) – the International Arboretum and Gardens will become a proverbial phoenix.

However, the present site’s configuration is not without disappointment. Its Tuggeranong Parkway boundary severs the site from Lake Burley Griffin; the interstitial land falling under the NCA’s planning control. As several competitors identified, extending the arboretum to the lake’s edge creates opportunities not only for an aqueous approach, but also for seldomexperienced views along the Griffins’ Water Axis. This obstacle can be surmounted by collaboration between the NCA and ACT.

By its November close, the ideas competition had attracted forty-five entries from throughout the nation. The next month submissions by Jones Sonter Architecture and Urbanism (Sydney), Taylor Cullity Lethlean Landscape Architects with Tonkin Zulaikha Greer Architects (Melbourne and Sydney), Inspiring Place (Tasmania), Anton James Design (Sydney), and Clouston Associates Landscape Architects (Sydney) were selected as finalists. The finalists’ stage two proposals are expected in May. Implementation of the winning design is anticipated to begin in July, with completion targeted for spring 2008.

Much of Canberra’s expansive designed landscape is limited to the coarse grain, routinely experienced only visually through an automobile windscreen. Although no less constructed, picturesque derivatives typify the city’s landscape and render the designer’s hand invisible. Fine-grain, intimately scaled and highly crafted designed landscapes, such as the late Harry Howard’s iconic National Gallery sculpture garden, are a rare phenomenon within the national capital’s public realm. This absence poses a rich opportunity for the arboretum’s design and several finalists’ concepts suggest that this void will be filled. The project’s scale, however, demands a design which passes both fine- and coarse-grain scrutiny.

Ultimately, for me, the symbolism of the project’s political dimension is no less significant than its eventual design outcome. Until now, many of the ACT’s planning and – to a lesser extent, owing to their paucity – physical design initiatives have reflected what might best be described as an active disinterest in Canberra’s status as the nation’s capital and as the remarkable product of Walter and Marion Griffin’s creative collaboration. Many ACT publications, for instance, are devoid of reference to either national capital or the Griffins. This absence is perhaps attributable to the ACT’s tenuous, if not competitive, relationship with its federal counterpart NCA. The Canberra International Arboretum and Gardens project marks a welcome departure. The competition brief and almost all of the project’s promotional material embraces the Griffins (albeit Walter more than Marion) and Canberra’s national capital status. When advocating the initiative, Minister Stanhope went so far as to assert that “we owe it to Walter Burley Griffin, we owe it to the future and we owe it to Canberra’s place as the national capital of Australia to actually allow ourselves with courage to imagine what is possible and develop it [the arboretum]”. Stanhope’s conviction signals, I hope, that the ACT’s national capital cringing is over.

CHRISTOPHER VERNON IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA.