Review

Early twentieth century architects believed that science, when applied to the erection of cities or buildings, could create a better society. That belief, in a debased form, mutated into the functionalism of the mid-twentieth century. Then behavioural studies, systems analysis, perceptual experiments and sociological theory all seemed to offer the promise of a quantifiable rational basis for design. Enter Charles Jencks and the post-modernists, who swept aside rationalism, functionalism and the expressiveness of the structure, as they went off in pursuit of memory, history and art.

French theory and graphic software have provided a new imagery that is often more appealing on paper than it turns out to be in reality, looking at the evidence of its buildings. This sense of inauthenticity has prompted many to go back with some nostalgia to the icons of modernism. Neo-modernism simply appropriates images and technology while forsaking old hopes and old ideas of the social.

The new International Style is now combined with information technology theory and high-tech materials. Will there be any room left for human behaviour or human hopes?%br% From October 13 to October 16, a quartet of Japanese architects, Fumihiko Maki, Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, Jun Aoki and Akuza Suzuki, were the guests of RMIT’s Spring Graduate Research Conference.

This distinguished quadrella showcased and explained their work, which was notable for its dazzling level of creativity, its bias towards culture, and its humanistic concerns. None of the work was seen as existing independently of the Japanese world, and more specifically of Tokyo as a city. It suggested relationships between the aesthetic and emotional apprehension of buildings and of the social and cultural forces that drive them. This is a drum I’ve been beating for some time, but it’s worth thumping it again here. It is a familiar argument in the social sciences: that values inform the choice of the facts to be selected.

Style has a limited life, or to paraphrase Barbara Kruger, there is no progress in pleasure. The Japanese architects demonstrated that architecture communicates. So too did Daniel Libeskind, when on October 17 he and Nina Libeskind visited Melbourne as it basked in the medal-strewn afterglow of the Olympics 2000. Daniel spoke publicly on four occasions: at the St Kilda synagogue; at the Span Galleries; at RMIT’s Storey Hall; and at the National Gallery of Victoria. He was interviewed on the ABC TV Arts Show by Norman Day, on ABC Radio’s Listening Room and on Arts Today, by Michael Cathcart. He spoke at three separate press conferences and was quoted widely in the national and local media.

Three exhibitions of his work were mounted. The Jewish Museum of Australia displayed eight Jewish projects, and it should be noted that the museum’s director, Dr Helen Light, was the dynamic force behind the entire project (calmly described by one of the curators as bigger than Ben Hur). The NGV mounted a Museum Projects exhibit involving six schemes and Span Galleries hung a show of Libeskind graphics and associated photos by Helen Binet involving about fifty items. A beautiful boxed catalogue was published which will remain eminently collectable.

Libeskind spoke in public both eloquently and urgently and offered bite after bite of quotable jewels (he easily imagines Alaska).

A pattern emerged that might be summarised like this: Architecture is a public art and the first thing is language. (Here he quoted Vitruvius). “Architecture is the link between the past and the future and we need it to propel us into the twenty-first century.” Buildings involve both private experience and public responsibility; the new can engage and inspire the public; the ethical aspect is fundamental; buildings are not abstract, they signal to and communicate with us; the building is not finished when it has been built.

Libeskind said, “Architecture is about optimism.” The word “radical” was constantly used. However, he also revealed an old-fashioned breadth of education and was able to discuss Ignatius of Loyola, Hegel, DNA, Bach, Dostoyevsky, Harold Bloom and Nostradamus on astrology. It was an assured display of political and cultural erudition, a depth of knowledge of the past in all its social and ethical forms. And it was all the more startling for that.

There are two critical cliches about Libeskind: one is that he is essentially a Jewish architect; the other is that he is a late entrant on the scene with no apprenticeship. Like most critical cliches these are half-truths that do an injustice to his prodigious creativity, the sweep of his curiosity, and his great capacity to listen. The Chancellor of Germany recently presented him with the Goethe Medal. After the ceremony Gerhard Schroeder gave him his personal phone number, remarking “just call me if you feel like a chat”.

The impact of this humanist on local students who nowadays withhold trust and are puzzled by curiosity is hard to gauge. But it will be some time before an architect holds our attention so much and prompts such rumination.

Peter Corrigan.

Interview

KB: In 1978 you wrote an introductory essay to John Hedjuk’s work, later published in Mask of Medusa, a collection of Hedjuk’s drawings and projects from 1947 to 1983. His work engages with literary and poetic narrative, allegory, and the intersection of literature and philosophy with architecture. Was he an important mentor?%br% DL: Yes, John Hedjuk was a great and inspiring figure and a seminal educator who fought against the current of corporate architecture.

There was an architectural renaissance in New York at that time. Many people were attempting to ask other questions of architecture, rather than adhering to a functionalist or corporate vision. He was a very interesting and important architect and I think his work is best understood when seen in the context of the New York Five.%br% KB: At that time the Oppositions project provided another position from which to assess the legacy of modernism.%br% DL: It provided a certain ground, but my work, even then, ran against the formalistic exploration of architecture so endemic to Cooper Union and other places. For me, form itself never seemed to be simply a metaphor of architecture within a constellation of set partis. I was a unit master at the Architecture Association, and it was a very important centre of architectural discourse, working with others such as Nigel Coates, Bernard Tschumi and Zaha Hadid. One has to see beyond the horizon of New York.%br% KB: Your relationship to the other European avant-garde, to the literary field of Proust, Joyce, Genet, and Artaud for example, is very strong. There are very few references to architects in your texts, and perhaps only Rossi and Tatlin are mentioned. I find this curious.%br% DL: Writers have more to contribute to a discussion of the city and its future. In its analysis of the modernisation of urban space, in its response, in its sense of the spiritual longings of huge populations, literary culture was in advance of the architectural avant-garde. So it is no coincidence that my references refer to this polymorphous field, not only to writers, but also to the ways in which writers represent experience. I am not only interested in writing but in what is experienced in the text. The discourse of architecture has been limited to a few very reduced notions of reference. Expanding that field to musical, literary, poetic, artistic, cultural fields locates architecture within the humanistic framework from which it originally arose. At the time, in the 1960s and 1970s, this was a movement against the grain. People discussed architecture then in terms of column grids or as certain projection systems. It was a tired world, at the end of its possibilities.%br% KB: Where did your interest in literature come from? Did you grow up in a family of readers?%br% DL: What else did we have? We had nothing but books. We didn’t have material possessions; we didn’t have cars, we didn’t have washing machines, we didn’t have any of these conveniences. All we had was a few good books.%br% KB: Which books?%br% DL: In Poland when I was growing up I had access to a number of books from Jewish literature including the Book, but it was an interest in connecting one’s experience to something else on the horizon. I was lucky to grow up in a family that appreciated books and believed that saving a book was more important than saving anything else. It was an appreciation for literature and a knowledge and hunger for something other than what one read in school.%br% KB: And an escape into another world of fantasy, imagination, creativity.%br% DL: Absolutely. But no, I would not say an escape. On the contrary, given the grim circumstances under which I grew up, it is a flight into reality. Reading, thinking and discussing literature open up the world.%br% KB: A flight into analysis.%br% DL: That’s right.%br% KB: Your Masters degree was undertaken in Comparative History and Philosophy at Essex University. Why did you make that choice?%br% DL: I wasn’t looking for a degree but I met Joseph Rykwert quite casually on a New York street and he invited me there. Subsequently, I met some interesting people and that gave me an opportunity to enquire further into things that were never really part of my professional education. Professional education everywhere is very narrow and limited. When I began running my own school of architecture at Cranbrook I attempted a completely alternative approach. I didn’t teach people how to draw grids and make axonometric projections. I asked the students to enquire: what is architecture for, why do we need it, what do we need? It was a very critical enquiry. We didn’t begin with a project for a house or a school or an office building. Many people thought that I was, that we were all, completely crazy.%br% KB: The process of institutionalisation is fascinating in architecture, for example, the discipline’s insistent move towards a literal translation of metaphor. We witnessed this process with deconstruction, with folding and now it appears again in hyper-surface architecture. Yet your work pursues its references differently. Descriptions like allegorical and analogical are rather imprecise to describe this process. A more elliptical relationship to experience is replicated in the building – no not replicated; it is a relationship, like an insistent but faint echo on a distant shore.%br% DL: You are right. I was never impressed by theories. Architecture is a very anti-theoretical discipline. No matter how many words one has to talk about architecture, it has its own gravity, its own mute opacity to what it is. This is the gap that people occupy in the relationship between theory and architecture. I was never an adherent to quasi-philosophical/ theoretical movements that reduce architecture to a text.

Of course you can read about architecture, but architecture is something completely other. This philosophical/theoretical engagement is very popular in the schools, which not only thrive on philosophy and theory, but on those philosophies and theories which generate particular kinds of teaching.%br% KB: There is a drive towards a pedagogical approach which unfolds design as a linear sequence, as if the design process itself can be explained backwards in a neat, linear narrative.%br% DL: Yes. If we dropped philosophy in favour of literature we would exchange the single, formulaic narrative for a multiplicity of possibilities. It is the difference between a Dickens novel versus a Peter Eisenman theory.%br% KB: Let’s discuss your drawings as another field of architectural enquiry. One reviewer, pondering your “translation from drawing to building” corralled your constructions in brackets, writing “Putting aside for the moment the constructions from the Venice Biennale in the 1980s”, but your early works from the late 1960s onwards include a series of maquettes and studies which investigate the making of a three-dimensional object. What is the relationship between these architectural works that you have produced over your entire career and the work you do now?%br% DL: There is no direct translation between drawings and models into architecture. Everyone thinks there is some sort of path, but there isn’t.

There’s an analogy, and one has to find a path of connections. I never drew or made models which represented hypothetical building types or hypothetical commissions that I might one day receive.%br% KB: The retrospective glance offers a certain clarity and there are continuities between the drawings you were producing in the late 1960s through to those produced in the 1980s.%br% DL: It is a retrospective clarity. One writer analysed several of my buildings, examining how they were derived from certain of my drawings. It was very convincing. He focused on the little parts and demonstrated that everything was already there, but it was also an exploration concerning all sorts of lineages, questions and fascinations.%br% KB: The Chamber Works series, exhibited in 1983, investigate the detonation of the line and what the line means in its relationship between graphic and material space. Can you comment on this observation?%br% DL: In my view they have very little to do with lines. They are about architectural space and architectural programs. They are enquiries, meditations of course, produced with pen and ink – a very traditional method. They were not made as an attempt to represent a hypothetical problem. They enquired and questioned, using a most archaic tool within a certain type of chamber; enquiring into the relationship between an act of thinking and the act of building.%br% KB: And the act of drawing.%br% DL: Absolutely. It was a physical act and not something that could be simulated on the computer screen.%br% KB: There has been a significant turn towards the computer-generated architectural image in recent years. Are we witnessing the demise of architectural drawing?%br% DL: Certainly I feel that architecture is in danger but it has always been in permanent danger. Today it is truly endangered because architecture is simulation, gloss and surface. Now anyone can produce architecture. That is a positive development because one doesn’t need to attend school, one merely needs the right program. This produces a spectrum of positive and negative possibilities but certainly drawing is disappearing and this is having an effect. I know this from personal experience.%br% KB: Yes, given that we’ve been discussing drawing as a speculative field of enquiry and as a space for thinking about architecture.%br% DL: Yes, the fact that people can simulate a drawing without ever experiencing what it might mean. Drawing is writing, writing is a kind of drawing, drawing with certain figures that have an accepted stability.

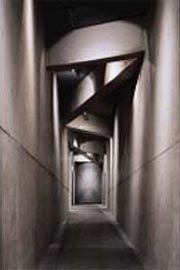

Any text is a graphic disposition of characters. A famous essay by Paul Valery relates the disappearance of geometers to the disappearance of western thought. If no one loves the surface and no one loves to draw a line what would happen to the world?%br% KB: If no one loves the surface in this way whether it is the surface of a sheet of paper or an etching pad, or of a building.%br% DL: Exactly. The easy capacity for simulating reality by vacating all the human aspects of what has been encountered in that reality is something new. One has to be aware of all this so that we do not produce architecture that is completely without soul and that is a computer simulation.%br% KB: Your drawings for the City Edge, the IBA Competition of 1987 are a very interesting reworking of the traditional architectural figure/ground urban drawing. Your building is not only an ornament as it is in these traditional figure/ground drawings, but also by being raised off the ground it refigures the ground beneath. Can you discuss this relationship to the ground?%br% DL: That’s a very perceptive reading. This was the last IBA competition and prior to this, over the three to four years existence of the IBA program, it had been dominated by the desire to resurrect the perimeter Berlin block with its internal courtyard. I trusted my own desire in this project to not resurrect the block, but instead to open the block quite emphatically towards new programs and completely new spatial relationships with the city. I’m glad that the jury saw this virtual possibility as a possibility of a new Berlin.%br% KB: What happened to the project?%br% DL: Unfortunately one outcome of the reunification process was the reclaiming of this land by a number of owners. It is now owned by numerous people and the land has been fragmented into parcels.%br% KB: Turning to some of your built works, I want to discuss the Berlin Museum Extension project, which won first prize in the 1989 competition and was subsequently built. The relationship between the Berlin Museum and the Jewish Museum presents an almost unrepresentable history and is a gesture towards reconciliation. Some of these issues are amongst those being debated in Australian public life as we assess the relationship between the history of the colonisers and Australia’s indigenous people. There has been a history of genocide as well in this country. The Berlin Jewish Museum obviously speaks to us from a specific historical experience but it opens up issues that are very important in the contemporary world – how to deal with an almost unutterable history and how to represent loss.%br% DL: It is a very specific response and it is very precise in terms of its architectural applications. It is not something I would have produced in another location.%br% KB: Yes, it is not a general model but we all bring our own readings to spaces. A quotation appended to your work on display at the current National Gallery of Victoria exhibition observes that the museum is also a space that the viewer takes away; it orders and opens another space in the mind. For Australians, this is one place to begin thinking about these issues.%br% DL: Of course. Unfortunately these events are not unique to a place.

But these events have to be regarded in an authentic way. They cannot be transposed as if they were types of experience, because that would reduce human experience to a generalised nothingness. They engage with the place, its history, with tradition and with people.%br% KB: In a number of your projects the relationship to history is mediated through individual figures and the work they have produced, such as your engagement with Alfred Dobin’s novel Alexanderplatz, in the 1993 Alexanderplatz Competition, or your use of Walter Benjamin and his texts in the Berlin Jewish Museum project.%br% DL: They are like angels. I do not resurrect them in an academic way to enable me to produce the project because then the project would be dead. You have to be lucky enough to encounter an angel and to follow it.%br% KB: George Steiner, in his book Errata, observes that “art and poetry will always give to universals a local habitation and a name”.

Architecture has often concerned itself with location as an outcome of making an architectural space but your work, particularly through its relationship to individual figures, appears to pursue a different sense of the dynamics of location and locating.%br% DL: Architecture produces this paradoxical effect. It is at once located somewhere but at the same time it denies its location by recreating or creating a new aspect that will re-engage the public. It is both in context – always already in the place where it is supposed to be – and always already out of context because it engages a particular public that has not been there yet: an unborn public. So it is also an opening. Architecture is always already in the world somehow, even when the walls have not yet been built, and yet the materialisation of architecture is an act that is so radical and so violent, one which stabilises and limits the dream. This tension is fascinating. It is paradoxical that architecture offers the greatest limitation but at the same time it offers the greatest freedom of being elsewhere.%br% KB: It is a paradox of all art but perhaps it finds its sharpest realisation in architecture because there has been such a strong determinist reading of the relationship between spaces and their inhabitation. Perhaps it has been more difficult to imagine this relationship in a shifting, more poetic, unstable way.%br% DL: People are more intelligent than that. People do experience something really extraordinary and that is why they are in this world.

Perhaps there is no discourse for reflecting on this experience whereas there was a traditional discourse. If we read the ancient and often decadent documents we sense that architecture was not merely about producing a building for the emperors but that it created the right flight path for the birds or something like that. People are aware that over the last few centuries architecture has been reduced to a certain formal discourse of planning but this does not mean this will always be the case. I think that people are beginning to demand greater freedom.

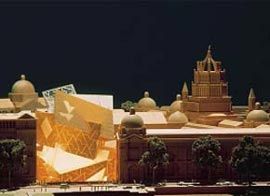

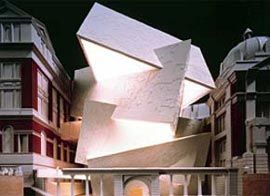

This is not necessarily the freedom to move walls around but it is an imaginative, poetic freedom.%br% KB: This imaginative poetic freedom appears in the fax that Cecil Balmond, your engineer on the Victoria and Albert Museum project, sent to your Berlin office. In it he writes of the fractal pattern and observes, “the fractal shiver runs up the building”. It is a lovely, joyous, celebratory fax for an engineer to send to an architect.%br% DL: It has been a wonderful relationship. He is not really an engineer, though of course this is his calling. He is more of a mystic of numbers. It has been a different kind of collaboration on the Victoria and Albert Museum project and a number of other works.%br% KB: Yes, the enigma of mathematics, particularly in the Christian mystical tradition, has been very important.%br% DL: Yes. He has written a book on “number nine” which is a very interesting piece. He brings other sensibilities to architectural engineering and to the measurement of structure. It represents a complete shift from high tech engineering ideas propelled by architects like Piano, and Rogers and Foster, towards a totally different notion of engineering which has little to do with norms of rationalising space.%br% KB: In fact it is a return to a very old tradition in architecture, one that is magical and mystical and relies on the speculative power of numbers.%br% DL: Well, because as you say, numbers are not merely there to be used. They have their own integrity and tell us something if we listen to them. Attempts to make the cheapest structure or the most rational building are not necessarily what people assume, such as making a square grid.%br% KB: In the drawings for the V & A extension, the force of the work seems to be directed towards the interior drama of the building, to the interior geography of that space, towards the path, the journey, the maze.%br% DL: Well the building was a response to the very severe conditions imposed by the three great A-listed buildings which flank it. The building explores the energy of these internal connections, connecting the six bridges to the existing fabric of the V & A. It is a physical and functional link to galleries built at different times, at different floor heights, at four levels. These are difficult to reconcile within a single, new space but at the same time it brings audiences to a new understanding of the architecture that surrounds them. It is very complex but it is also a very simple idea which contributes a twenty-first century building to this extraordinary composition of ideas and spaces.%br% KB: It also discovers other ways to engage with history, outside, for example, those proposed by the post-modernist historical quotation formula.%br% DL: That phenomenon has almost passed. People are much more aware that the material, spatial, functional experience is not as shallow as that prescribed by post-modern theorists. The V & A architects were very radically modern architects.%br% KB: Absolutely, you can see that in the cross-section drawings, in that beautiful structural engineering subsisting beneath the wedding cake dome.%br% DL: Not only that. They were probably the first architects to use this material and the first to experiment with social programming. The V & A was the first museum in the world to incorporate a restaurant. It was a wonderful vision. Museums were not merely for the elite nor just for education and culture, but for working people and to enable people to do something else with themselves.%br% KB: You have a number of museum projects underway. What attracts you to the museum building? And are there any architectural commissions you might refuse?%br% DL: No, I would never refuse something. I have been fortunate. I began with an important museum and subsequently became involved in museum architecture and the museum debate. These are important projects because they are public, and I’m probably the only architect in the world whose practice is completely based upon public buildings. It is based on public competitions and a discourse with the public about the requirements of programs. I don’t have private clients. Of course I am entering a new phase now, but it has not been my choice, rather a lucky constellation.%br% KB: Are there particular kinds of building you would hope to be commissioned to build during your career?%br% DL: I never regard architecture in this way. I want to remain open and see what is true, what is real and where it leads. I hope to be involved with things that are important such as the building of cities and the building of public spaces. These are actually the most important things.%br% KB: Finally, what effect has your peripatetic life had upon your architectural research?%br% DL: It has had an effect because most architects remain in one place and cultivate their networks. Being in different places gives one a new perspective and a more global sense of what is happening.%br% KB: George Steiner, in attempting to partly explain some of the forces driving anti-semitism writes of the Jewish person as an unwelcome but necessary guest knocking upon the door of a house.

He uses that figure to remind us all that we are guests in each other’s houses. Your comment has reminded me of that observation.%br% DL: The idea of home should be examined. People assume that they are at home because of a tribal blood relationship, but who is really at home? This becomes very clear when one moves, and not merely as a tourist but when one lives within and involves oneself in other cultures. Everybody claims to be at home. This gives one something to think about.

Dr Karen Burns is a Melbourne based architectural historian and theorist.