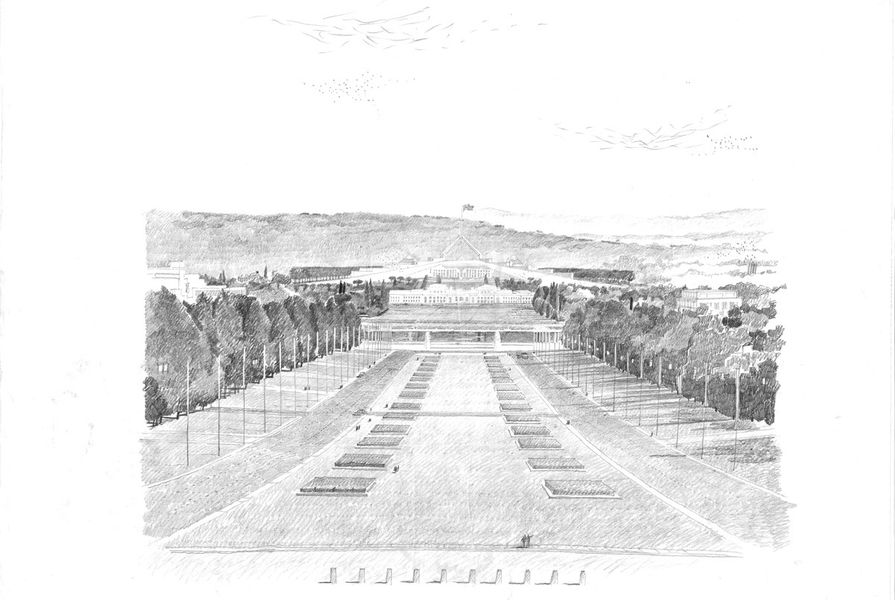

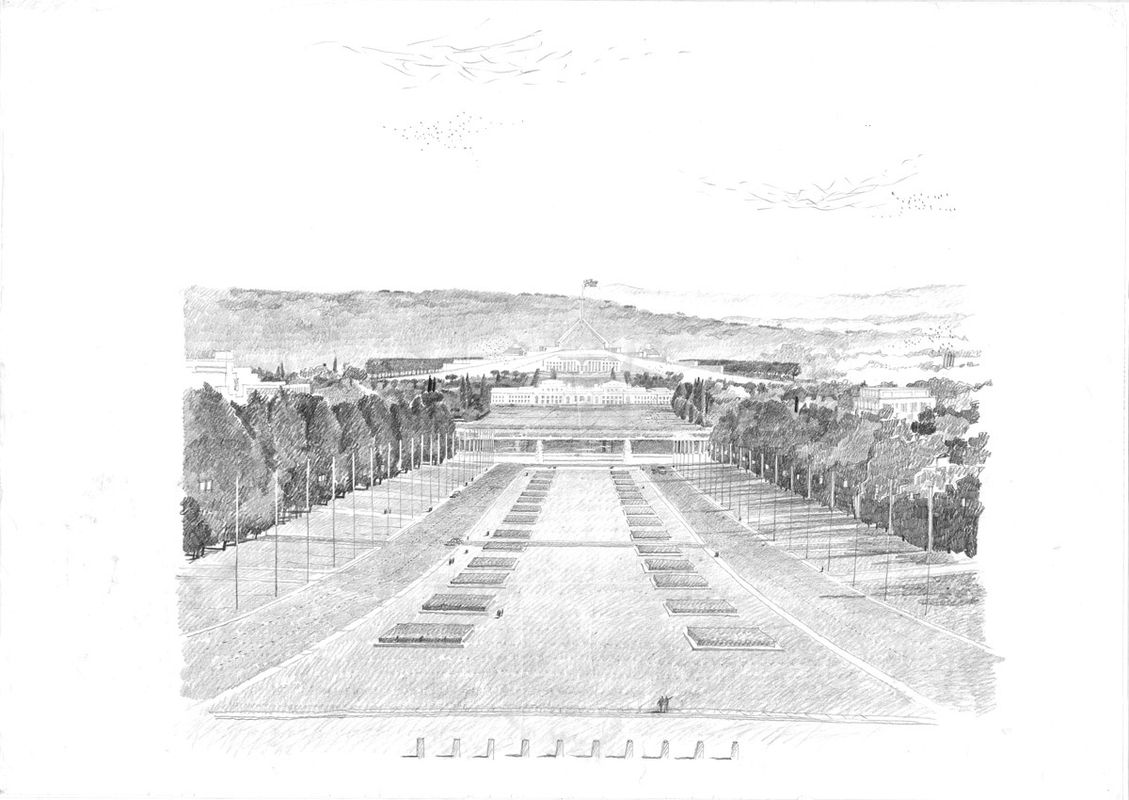

On 2 September 2010 Romaldo Giurgola reached his ninetieth birthday. It was commemorated by an exhibition at Parliament House – Lines that speak: Architectural drawings of Romaldo Giurgola (3 September – 31 October 2010). Curated by his former Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorp (MGT) colleague Pamille Berg, the display and its contents were no less elegant than the venue. Most of the exhibited drawings were executed with humble pencil on paper and ranged from elevations and plans to expansive exterior perspectives, including ones of Parliament House. Not unlike Marion Mahony Griffin’s earlier Canberra competition renderings (1911), Giurgola’s Parliament House views were undoubtedly a persuasive force in the later contest’s outcome (1980). In harsh contrast to our twenty-first-century world of computer-generated, hyper-realistic and often sterile architectural imagery, Giurgola’s renderings – like Mahony Griffin’s and despite the passage of time – exude a humane intimacy.

On the exhibition’s heels in November 2010, Aldo (along with MGT collaborators Berg and Hal Guida) participated in a National Archives of Australia symposium, Designing for Canberra. The Italian-born architect reflected there upon the extraordinary experience of designing and then realizing Parliament House. Surprisingly, the Australian design contest for the building was not the first catalyst to put Canberra and Walter Burley Griffin into Giurgola’s architectural imagination. In 1938, Aldo enrolled in the architecture course at Sapienza – Università di Roma. Mussolini’s Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana – a set piece within his Esposizione Universale Roma initiative to enlarge the Italian capital – was rising ominously. Around this time, Giurgola’s professor Ludovico Quaroni alerted him to Griffin’s Canberra layout. It seems that the American’s design for an Australian democracy had, paradoxically, found resonance in Fascist Italy. For the young student, the city plan was impressive in its perceived compatibility with the natural environment. It was, however, an inauspicious time to begin study; the world was soon at war and military service intervened. Giurgola eventually graduated in 1948.

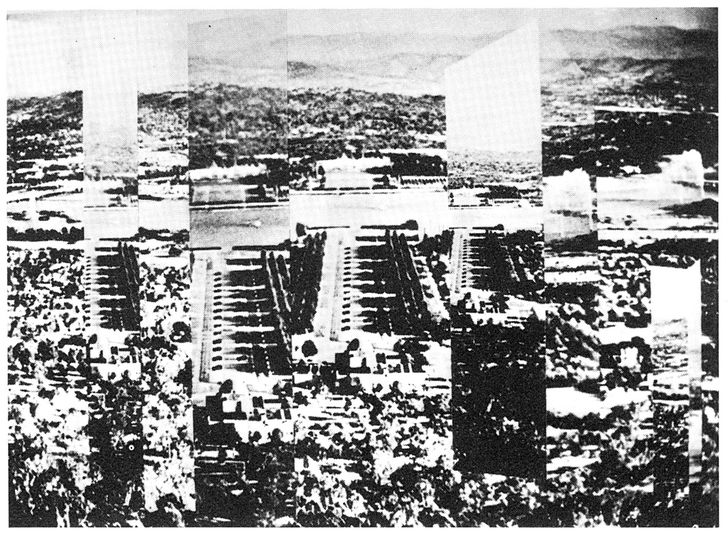

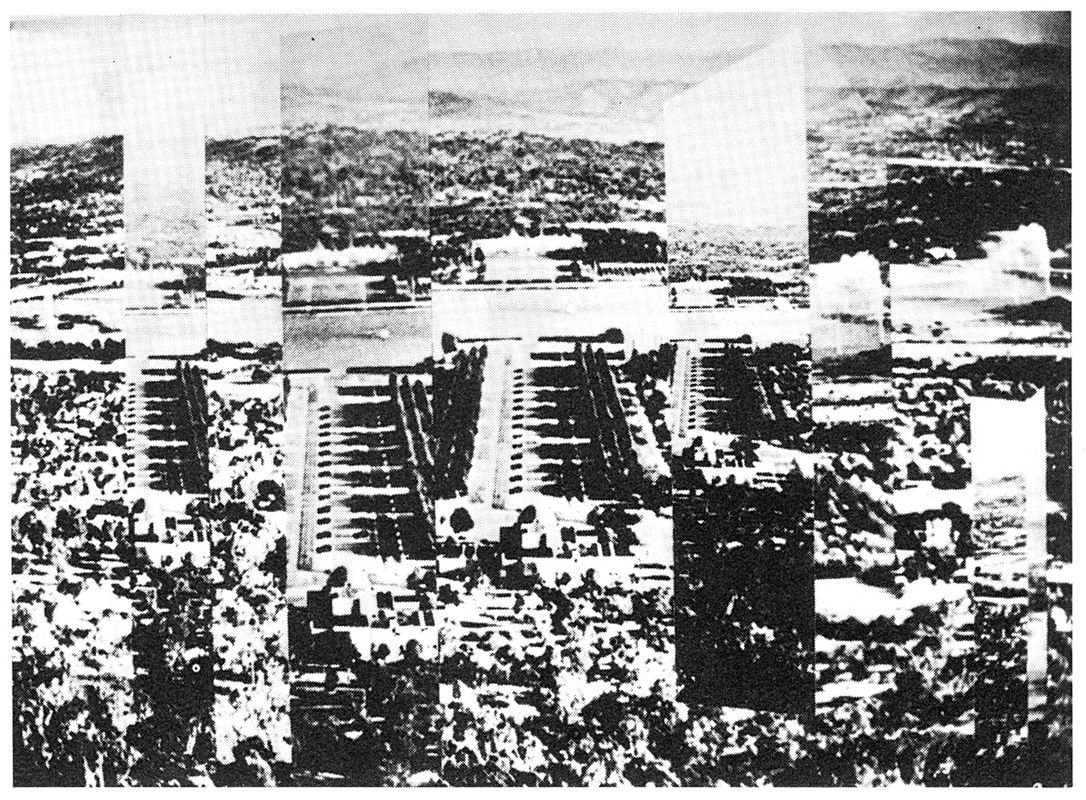

Mitchell/Giurgola Associates’ entry in the Walter Burley Griffin Memorial competition of 1975, published in Process: Architecture, No. 2, 1977. The proposal shows a series of vertical mirrors reflecting the city from the vantage point of Mount Ainslie.

There was another pre-Parliament House catalyst. In July 1975, nearly forty years after Quaroni introduced Giurgola to Canberra, the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) launched a Walter Burley Griffin Memorial design competition (Mahony Griffin had then yet to attract recognition beyond “the hand that held the pencil”). This commemorative work, envisaged on top of Mount Ainslie, was intended to mark the centenary of Griffin’s birth as well as his native USA’s bicentennial the next year. Submissions were due in October. Mitchell/Giurgola Associates (MGA) entered. By this time, Aldo was living in America. Indicative of the landscape sensibility that would later pervade Parliament House, Giurgola’s scheme comprised an assemblage of monolithic pylons, clad with text-inscribed glass and mirrors, composed, in his words, “in such a way as to get you to see the city and the configurations of the land”. Through reflection and refraction, the mirrors ethereally “deconstruct” and reproject the Griffins’ crystalline geometry. “So,” the architect explains, “Griffin comes into the equation –a continuous relation between the national land and the mountains, as in Mahony’s drawing.” Save for its site, Giurgola’s ensemble, to my eye, recalls Luis Barragan’s Satellite City Towers (1957). Disappointingly, MGA’s submission did not place. Although unsuccessful, the next year Giurgola would find himself constructing a cultural centre in another Southern Hemisphere designed national capital: the Casa Thomas Jefferson (1976) at Brasilia.

I have always felt affinity with Giurgola; Canberra profoundly and unexpectedly redirected both our lives, eventually prompting mutual relocation from the USA to Australia and culminating with Australian citizenship. I first experienced Giurgola’s work at first hand in 1982. Then an architecture student, I set out on a pilgrimage to St. Louis to visit Louis Sullivan’s Wainwright building (1890-91); Sullivan continues to loom large in my pantheon of architect greats. Reaching the Missouri capital after half a day’s drive from Chicago, I found my way to the rust-coloured, terracotta-clad, ten-storey building. Named for its client, the Wainwright was originally conceived as a commercial office block. Now, however, it had taken on public dimension, accommodating state government offices and, more palpably, gaining additions and extensions (1981). I was struck by the new structures’ disciplined, restrained deference to the Sullivan masterwork. No less impressive was that the additions were configured to form courtyards and plazas, making a continuous transition between old and new. “Alhambra-esque” rills and pools interconnected interior and exterior. Encountering these new constructions was an epiphany; my focus on Sullivan and the past had come at the expense of the present. Research upon my return revealed the authors of this elegant ensemble to be MGA (in association with Hasting + Chivetta) and that victory in a national design competition (1974) had won the commission. As I would later discover, courtyard pool and rill devices reappear in Parliament House. Similarly, in his magisterial design of the new St Patrick’s Cathedral at Parramatta (2002), Giurgola reapplied his exquisite spoliation technique, fusing old with new.

At Designing for Canberra, Giurgola astutely identified that “behind the [Griffins’ Canberra] drawings is a strong perception of the humanity of the place.” Humanity is no less discernible throughout Romaldo Giurgola’s own distinguished oeuvre. As first revealed to me at St. Louis, Aldo’s architecture is, foremost, humane; it sensitively considers, responds to and reinterprets what preceded it. Or, as Aldo explained to me in January, for him architecture begins with consideration of “content,” not form. His work is antithetical to, for instance, the bombastic, if not narcissistic, species of architecture to be found nearby on the Acton Peninsula. As epitomized by Parliament House, Giurgola’s buildings are timeless and transcend fashion. A sensitivity to and compatibility with the Griffins’ Canberra layout was central to Giurgola’s Parliament House success. Given that the national capital’s centenary is fast approaching and the city’s authors remain without a monument, it would be timely to revisit Giurgola’s 1975 Griffin memorial design. To realize it now would simultaneously commemorate the Griffins, the national capital they designed and, indirectly and discreetly, the remarkable architect that is Romaldo Giurgola.

Footnote in history

Announced in July 1975, the Walter Burley Griffin Memorial design competition was conducted in two stages. Along with the NCDC, the contest was sponsored by the National Memorials Committee and the Administrator of US Bicentennial Activities. The NCDC planned to complete construction of the winning design by 24 November 1976, the centenary of Griffin’s birth. According to the competition brief, stage one entries were due by 17 October 1975, with adjudication to follow that same month. Jurors included town planner and Griffin scholar Peter Harrison, the NCDC’s Tony Powell, and celebrated American town planning authority Edmund N. Bacon. Five entries advanced to the second stage (24 November – 13 February 1976). Finalists included: 1) Robert T. Crane III of Cope and Lippincott, Architects, Philadelphia; 2) Henryk Swarce, New York; 3) Ferdinand Nolte, Hunters Hill, NSW; 4) Malcolm Munro of Scott and Furphy Engineers, Canberra; and 5) Walter Wolczynski and Edward Herbst, Morristown, New Jersey. Robert Crane’s design emerged as the second-stage winner, although it is unclear precisely when. Incidentally, Crane was then only on secondment to Cope and Lippincott; he was actually a member of MGA.

In the political upheaval surrounding the November 1975 dismissal of the Whitlam government, the project soon languished. By April 1976, with a new government in place, cost had become a pressing concern. That month, Architecture Australia (AA) reported that the government had “shelved” the memorial, laconically assessing that Griffin would be remembered only “if we can afford it”. News of the project’s demise apparently didn’t travel fast. In May, a hemisphere away, The American Institute of Architects Journal reported that the memorial’s ground breaking would be on 4 July and the finished work unveiled on 24 November 1976. Back in Australia, the Griffin memorial was not, apparently, completely dead. In June 1976, AA noted that documentation of Crane’s prize-winning design was going ahead to “bring [it] to a stage where work on building can begin quickly when the Government decides that it can afford to have the memorial”. Whether or not this actually happened is unclear; it may well be that the fully documented design lies forgotten amongst the NCDC’s voluminous records. Nonetheless, in the August AA, the NCDC, likely in response to criticism of its decision to shelve the project, “point[ed] out that while the memorial has been dropped from the current financial program, it is in the Commission’s five year program as normal work”. More than thirty-five years later, Walter and Marion are still waiting.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 17 Sep 2012

Words:

Christopher Vernon

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2011