The pavilion has been an important building type for the development of architectural knowledge — from Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park to Sverre Fehn’s Nordic Pavilion for the Venice Biennale, to Carmody Groarke’s rooftop restaurant in London, to the entire Serpentine pavilion series in Hyde Park. With each of these exemplars came the announcement of a new practitioner of note into the international discourse or a moment of brilliance from one we already knew, and a building that pushed boundaries — either technically or poetically, or often in both these ways and more.

But pavilions are not perfect. Rarely waterproof, lightproof or fully functional, their delight is in their impermanence, imperfection and the errors that we can forgive them for, given their short lives. The mismatch between these qualities and the Giardini in Venice has always caused dif- ficulty for the country pavilions at the Venice Biennale, caught as they are between temporary use and a permanent existence. This disjunction is no better seen than by comparing Fehn’s remarkable but “impractical” Nordic Pavilion (impractical if showing artwork under gallery-standard lighting levels is the benchmark) with Denton Corker Marshall’s (DCM) winning entry for the replacement of Philip Cox’s Australian Pavilion. While the Nordic Pavilion demands spatial engagement from the exhibitors and an engage- ment with the context beyond the pavilion’s glass walls, DCM’s project — if rumours are correct — is the subject of a highly constrained brief that privileges the well-proportioned “white box” orthodoxy of the last hundred years, even though the pavilion will be built for use throughout the next hundred years. DCM’s solution — previously aired in the international ideas competition held by Di Stasio a few years ago — seemed a perfect alignment with the procurement process that “fetishized” previous experience, risk mitigation and a standard reading of the art display paradigm.

As the creative directors of the last exhibition to be held in the current Australian pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, we and our collaborators Toko Concept Design are determined to send off Cox’s much-maligned temporary pavilion with dignity. Eschewing the rarely resisted temptation to deride and complain about this quickly designed and accidentally long- standing structure, we sought its better qualities and its potential as we developed the show.

Visiting the pavilion last September as it housed the Hany Armanius show for the Venice Art Biennale, we found the pavilion stripped back to its original condition, or at least something approximating it. With the skylight open and the central tree visible from the stairwell as it pivoted around it, the pavilion made more sense than it had in many years. It has been adjusted, coloured or blacked out to suit varying pragmatics and egos over the past decade. With the original logic visible and the inside-outside relationships that drove the original design on show, it was no easier to display artwork in the domestically scaled pavilion, but it was far more enjoyable to experience than it had been for many years.

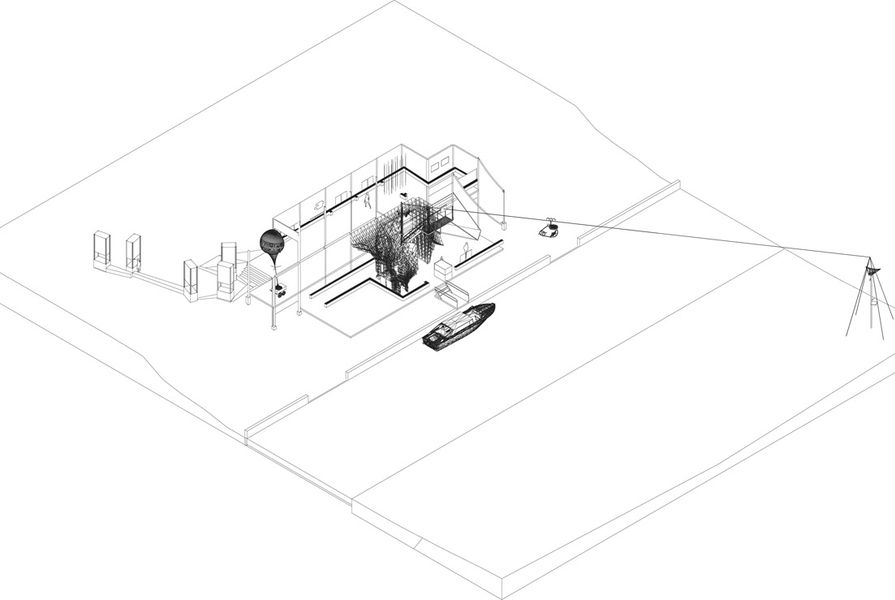

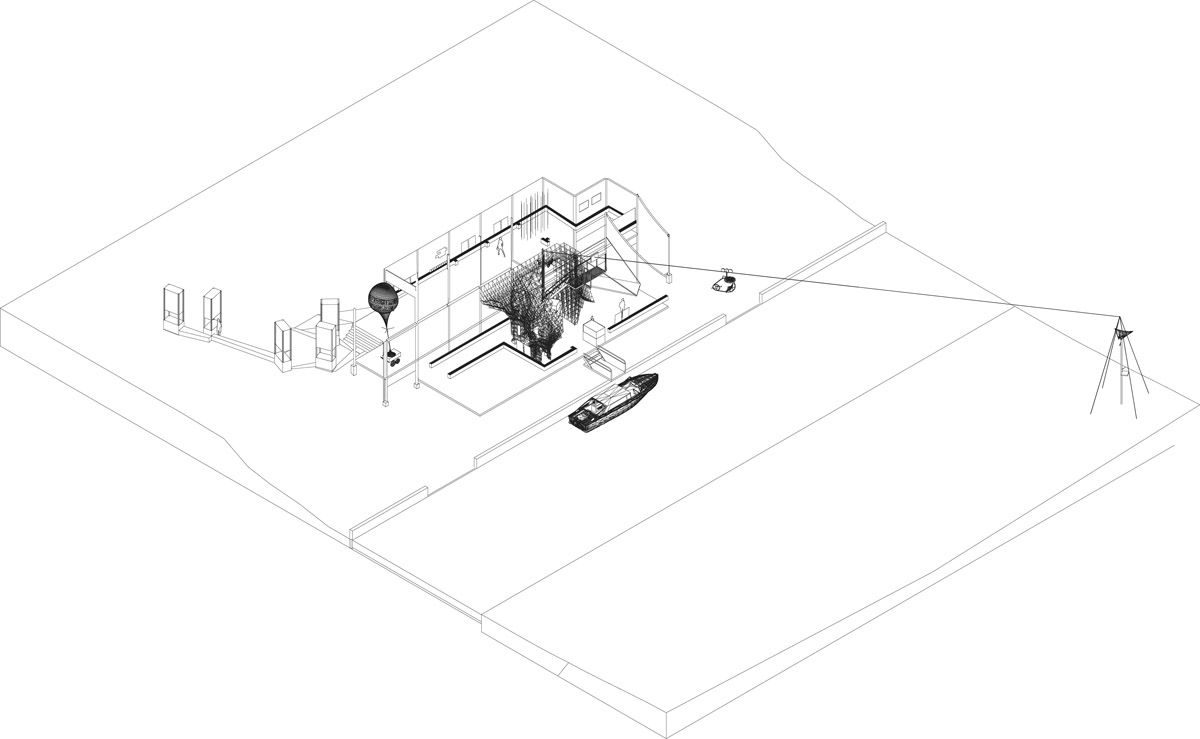

This experience of the pavilion in its near-original state led us to con- sider how we could use this as the basis for the architecture show without being constrained by those aspects of the building that have caused difficulty over the years, such as the split level, room proportions and wildly variable light levels throughout. With an incredibly diverse set of exhibitors who all work in unusual ways, the opportunity existed to use the pavilion as a form of infrastructure that will support their endeavours rather than contain them. Starting with Richard Goodwin’s zip line across the canal and into the skylight window, each exhibitor started breaking free of the pavilion as they suggested projects that in many cases span the entire Giardini, either conceptually or physically.

Moving from a paradigm of the containment and isolation of the exhibit- ing space to one of a supporting infrastructure subsequently places different priorities on the space and allows for a much broader definition of what is acceptable in terms of exhibiting the art of architecture. For example, one contemporary trend is towards salon-style shows that invite the eccentricities of the space into play with the works on show. At the opposite end of the spectrum lies our approach to the Venice Biennale, where the pavilion is used in ways that do not depend on traditional lighting and spatial arrangements, as instead it supports a range of performances, events, actions and specific in situ works that acts as a bridge between the environment and the exhibition space. This approach to an open exhibition marks the profound difference between an art gallery and a pavilion. A pavilion is almost always a structuring node among a larger field of events.

By using the pavilion as an infrastructure in this way, one can harness the best qualities of the building. The pavilion then becomes a portal through which each exhibitor’s work can be viewed in relation to its context, rather than a coffin in which a sombre audience experiences a lonely and decontextualized installation.

Anthony Burke and Gerard Reinmuth, working in collaboration with Toko Concept Design, head the creative team for the Australian Pavilion at the 2012 Venice International Architecture Biennale. The Architecture Biennale runs from 29 August until 25 November.

From a dossier in the July/August 2012 edition of Architecture Australia, on “Australian Style.”