Review Sandra KaJI-O’Grady

Photography Brett Boardman

Views to established trees and gardens form an essential element of the Lowy Centre.

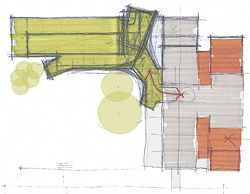

The design of the Lowy Centre has been used to facilitate new links across the campus, including a major pedestrian entrance.

The west elevation and main entrance to the building.

Oblique view of the south facade.

Sketch showing campus connections.

The northern facade, with the new pedestrian route framed by the green inhabited bridge.

Looking across a laboratory space to the write-up areas, with garden views.

Laboratories opening onto the atrium.

Corridors are generous and multifunctional to encourage socialization.

Universities across Australia have embarked on major campus development programs in the past decade, with much of this building boom housing newly established research partnerships. UNSW’s Lowy Cancer Research Centre is the most recent to be completed, bringing teams of researchers in adult cancer from the Faculty of Medicine together with the Children’s Cancer Institute Australia. There are significant cost savings in sharing expensive equipment and laboratories but this is only one motivation in co-locating research teams. The higher aspiration is that groups of previously isolated researchers will find common ground, discuss their work and make breakthroughs. The question for architecture centres on the problem of spatially supporting planned research as well as serendipitous exchange.

The Lowy Cancer Research Centre was won by Lahz Nimmo Architects in association with Wilson Architects, through an invited competition process. Wilson Architects’ contribution was focused on satisfying the first ambition, the provision of quality laboratories to facilitate research – the practice previously worked with John Wardle Architects on the Queensland Brain Institute. Both the Lowy and QBI are primarily laboratory buildings (the Lowy has four floors of P2 laboratories) and both buildings benefited from Wilson Architects’ expertise in the sensible resolution of parallel zones of equipment, benches and write-up. The researchers I spoke with are happy with the flexibility and operational aspects of their laboratories and the ease of moving between floors via an internal P2 lift and stairs.

To fulfil a laboratory classification, solar penetration is strictly eschewed in the designated spaces and the decision was made to keep the band of equipment to the north and write-up to the south of the laboratories. Consequently, researchers always have the relief of a pleasant view of a mature garden – a view enriched by stepping up the ceiling height to the south, making large full-height windows possible. The southern facade is an attractive composition of glazing and vertical bands of green aluminium composite panel, while the northern facade, protecting the equipment rooms behind, is heavy and less visually satisfying. Unhelpfully, the project floor area increased by 30 percent during the design process, and this eliminated any potential for setting the northern facade further back from the street. Attempts to relieve the overall bulk with punched out rooms are further compromised by the incomplete state of the project. The adjacent Faculty of Medicine building will soon be renovated – again by Lahz Nimmo in association with Wilson Architects – and this includes a new facade to the north that with luck will see the public face of the building better resolved. In its current state it is somewhat schizophrenic; the public face of the project is at odds with its welcoming and lively interiors.

The challenge of getting around four hundred researchers, led by professors who are regularly out of the building and in the hospital, to intermingle is the key ambition of the project and it is in these attempts to sponsor conviviality that the building gets interesting. Firstly, the project substitutes monumental and complete form for a more porous and open-ended architecture with physical links and views to other buildings on and off campus. The building form is literally and metaphorically concerned with connection and bridging. Secondly, the project thickens and augments the corridor – the traditional space of academic socializing and gossip – using it to form a distributed network of informal kitchens and lounges, semi-open-plan work areas and programmed event spaces. The core of these informal social spaces bridges the upper levels of the new building with the old Wallace Wurth Medical Faculty and takes a diagonal path between the two that approximates a natural inclination for walking. Forming an inhabited bridge, this is in turn used to frame what has become a major pedestrian entrance to this end of the campus, as well as to both buildings and the Michael Birt Gardens beyond. With its foyer and circulation located adjacent to the existing medical faculty (rather than at the west end as originally briefed), the project has been able to generate a positive experience of social exchange between new and old elements, but also in and out of the campus. The connection between UNSW and its context is more than symbolic, for the relationship between clinical and academic work is close.

The foyer is an expanded space that reaches vertically through the six floors of the building, its perimeter shifting to introduce a dynamic of interpenetration. From the photographs I anticipated that the foyer would be a monochromatic space of green, green, green. In reality, there is a lot of green, but it is balanced by planes of white, walls of timber, dark grey floors and furniture that introduces orange and brown. Indeed, there is a remarkable attention to delivering a tactile, colourful and carefully thought through interior of purpose-built cabinetry and flexibility. The vibe is that of a bar and lounge, not an institution devoted to science and bench space, yet these are bars and lounges that can easily be reconfigured for presentations and meetings, and are equally comfortable for a lone researcher with her sandwich.

It has been evident since the beginning of the project that the success of Lahz Nimmo Architects and Wilson Architects’ winning proposal lies in a clear organizational schema that manages to encompass the strategic ambitions of the university as well as the detailed technical requirements of the researchers. The key elements – views to the gardens, intense use of circulation as a social condenser, upper-level connections to the Wallace Wurth and a skewed western end that addressed the campus and a major eastern entry – have survived negotiation and compromise and, more specifically, the builder’s value management process. Materials and details have changed to accommodate the demands of value management, but it is only in the northern facade that one feels that this has in any way lessened the outcome. Most importantly, the informal social spaces that are typically the most vulnerable to pressures in the process from briefing to occupation (given that they do not have a quantitative brief) have been preserved and are working. In similar research buildings it is almost always the informal and formal social spaces that users complain about – atria that are too cold, hot, noisy or exposed to comfortably lounge in, reading and discussion areas with empty shelves that were meant to be shared libraries, kitchens that remain unused. For the Lowy Cancer Research Centre, these spaces have been so successful that the users immediately exceeded the provision of refrigerators. It is a credit to the architects that they are now designing additions to the kitchens to accommodate their popularity.

Sandra Kaji-O’Grady is professor of architecture at the University of Sydney.

The foyer stretches through the building as an atrium, with the thick green horizontal elements restoring a sense of human scale.

LOWY CANCER RESEARCH CENTRE, UNSW

Architects in association

Lahz Nimmo Architects and Wilson Architects.

Landscape architects

Wilson Landscape Architects.

Structural and facade engineer

Taylor Thomson Whitting.

Mechanical engineer

Knox Advanced Engineering.

Hydraulic and fire services

Warren Smith and Partners.

Electrical and lighting engineer

Aurecon.

Communications and IT

University of New South Wales Facilities.

Fire engineer

Arup.

Acoustic consultant

Acoustic Studio.

BCA

Lend Lease Design.

Medical gases consultant

SC Medical Gases.

PCA

Steve Watson and Partners.

Client

University of New South Wales.

Project manager and builder

Bovis Lend Lease.

Photography

Brett Boardman.