The eastern facade of the Lyon housemuseum. The brickwork of the boundary fence incorporates overscaled lettering of the street name, “FLORENCE”, reinforcing its institutional scale in a suburban setting. Image: Dianna Snape

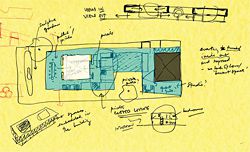

Concept sketch of the housemuseum.

The double-height white cube, reminiscent of the picture gallery at the back of Sir John Soane’s house/museum in London. Artworks: Rose Nolan, Rose Nolan 2000/2001, 2000–2001 (far left, upper floor); Patricia Piccinini, Sheen, 1997–1998 (ground floor); Jim Paterson, The Elephant Man (I–V), 1989 (far right, upper floor). Image: Dianna Snape

The music room. Artworks: Brook Andrew, YOU’VE ALWAYS WANTED TO BE BLACK (white friend), 2006 (left wall); John Nixon, Untitled Colour Groupo E (Random), 2008 (right wall). Image: Dianna Snape

The dining room or boardroom, lined with Howard Arkley, Fabricated Rooms, 1998. Image: Dianna Snape

The rear gallery corridor on the ground floor. Artworks by Callum Morton: Farnshaven Illinois, 2001 (digital print) and Habitat, 2003 (model). Image: Dianna Snape

The children’s bedrooms are demarcated from the quasi-public domain of most of the house, but still hung with art. Artwork: Jon Campbell, Spearmint Baby, 1989. Image: Dianna Snape

The black cube for video and other media works. Artworks by Patricia Piccinini: Lustre, 1999 (projection on walls) and Car Nuggets, They’re good for you, 1998 (three red nuggets). Image: Dianna Snape

The kitchen and living area. Artwork: Patricia Piccinini, Truck Babies, 1999. Image: Dianna Snape

The living area, showing the connection to the white cube. Image: Dianna Snape

The Lyon housemuseum is a house for a family of four people and simultaneously a museum for a collection of works by Australia’s leading contemporary artists. And museum it is – we are considering an establishment with visiting hours, arrangements for scholarly access, a website with advice on public transport routes to get there, and an events program including recitals on a high-tech pipe organ. The clearest architectural references and devices are museological rather than domestic. The building is organized around two spaces overtly meant for art – a cube volume with white painted walls on one hand; a corresponding black cube for video and other media works on the other. These fit within a building that seems to have been conceived as a simple gabled enclosure which has undergone various geometrical operations – shears, folds, subtractions. Rather than being gratuitously innovative, these are geometrical transformations which can be grasped directly. It is as if transformational procedures something like those in Eisenman’s early sequence House I to House X have been applied, instead of to a Corbusian villa, to a simple portal frame industrial shed (with the end gable profile just a hint of the roofline of the Vanna Venturi house). Between the envelope and the two cubes, rooms and corridors and necessary facilities for art and for domesticity are generously arranged.

The ideas of white space and black space are powerful and generic, but the references to architectural precedent drawn from the back catalogue of museum architecture in this building are also specific. The white cube, hung with paintings at two (and potentially more) levels and featuring openings from upper-level spaces adjacent, brings to mind the picture gallery at the back of the Soane house/museum in London, a perennial architects’ favourite. That space’s ingenious hinged panels facilitate the simultaneous hang of many paintings and prints, and it is perhaps from these that the pivoted wall/door at one corner of the Lyon housemuseum’s white cube (and pivoting elements elsewhere in the building) derive. The piercings in this white cube space, opening to its outside, allude also to Brian O’Doherty’s influential critique of the inward focus and dissociation of art from life in twentieth-century art museums in his book Inside the White Cube. And thus the references multiply. The housemuseum’s in-between spaces have also been designed with other museums in mind. The dimensions of the upper-level corridor on the west side of the building, quite tightly hung with smaller works, were devised with the model of the corridor spaces at another famous and salubrious house/museum, the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice. And, thinking of the local, the two cube spaces around which the building is arranged and its rectangular overall form (somewhat distorted to be sure) are perhaps reminiscent of the parti of Roy Grounds’ National Gallery of Victoria, with the cubes corresponding to the south and north courtyards, now filled with galleries in the Bellini renovation, the middle court lost as it has also been in the unfortunate NGV revamp. The deployment of timber veneers as a surface on which to hang artworks is also mindful of the pre-Bellini NGV.

These references are both important to the architectural inception of the Lyon housemuseum and incidental to it. What we might make of them is that, as Philip Johnson put it, we cannot not know history. Perhaps more accurately, architects of Corbett Lyon’s generation do not not know history. But although a kind of referentiality, and in this a deference, to other architectural achievements is entailed in the building, the housemuseum does not require of us that we have this knowledge to experience it richly. Nor is any particular reference key to the building, adequate to unlock it. Along with the almost diagrammatic clarity in some design gestures here, overall it has what might be called after Gianni Vattimo a weak strategy, such that the question of how design claims legitimacy in architectural history and genealogy is raised but not resolved.

This is important in the place’s role as an art museum. Confident as the Lyon housemuseum is in its knowledge of architectural precedent, this does not get in the way of it as an environment for seeing paintings and sculptures and other contemporary works. It really does not matter, in looking at the vast Howard Arkley sequence folding across three walls in the upper-level dining room, whether or not the space has some specific antecedent, and apart from having learned that this arrangement reproduces how this particular Arkley work was once shown at the Venice Biennale, I don’t know what the allusions are that might be floating here. Similarly, with the treatment of the extraordinary Callum Morton model of Moshe Safdie’s Habitat ’67 in a niche off the back corridor of the ground floor. No doubt there could be some wispy sketch in an archive box somewhere that identifies a noble architectural ancestor for this space. What came to my mind, however, in the way this work is often glimpsed across the building, from a distance, is how Habitat the original is seen from downtown Montreal – across the river a long way away. The Arkley and the Morton are two of only three works more or less permanently installed, the other being an Andrew Brook work across one wall of the space that also houses the organ. All the other works in the developing housemuseum collection will change in a revolving hang and as the place’s potential for various kinds of installations and events unfolds.

How is the housemuseum a house? This is not a big house with a good collection of domestic-scale works – the art here, through quality and often through size, is meant for the big spaces of the museum. Nor is it a museum with an apartment, as, say, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art contains an apartment for its lucky director. Rather, the domestic is casually insinuated here and there throughout the building, perhaps in the manner of a warehouse studio also serving as a habitation. Some spaces are clearly more conventionally demarcated from the quasi-public domain of most of the interior than others, especially the bedroom suites. But even in the two children’s bedrooms the walls are hung with art. Here, the Peggy Guggenheim seems the most significant of precedents. Because it was made of a congeries of “found” spaces the Peggy Guggenheim museum does not hierarchically organize and separate public and private, and bedrooms open directly onto Venice’s principal public space, the Grand Canal. The Lyon housemuseum has its interface with the scale of the city also, though not quite so majestically. Its site on inner-suburban Cotham Road, among the quasi-public institutions of Kew’s schools and clinics, is on a tram line that knits it into an urban network. The over-scaled street names in the remarkable boundary fence brickwork reinforce this institutional scale; the letters LHM astride the housemuseum’s roof and landscaping address the urban scale from the different vantage point of Google Earth …

The threading of the domestic through the housemuseum may seem casual, but it is not random. Various museum “functions” and domestic ones coincide: the library could double as a bookshop, a study as an archive, the dining room as a boardroom and so on. One of the most intriguing aspects of the interior is a loose family history in words, phrases and names inscribed in broad sweeps into the timber veneer surfaces of walls and ceilings. It is not possible to discern this just from looking, but this textual “wallpaper” is organized to form the word ART writ large – as large as the scale of the building. This device invites all kinds of interpretations – art and family coincide? Art subsumes domestic history? The general is made of the specific? However this should be construed, I was curious to know just how the people who spend most time here – the family – might negotiate the ambiguities of a housemuseum from day to day. Museums, after all, have a reputation for being uncanny, especially when the visitors are gone (think Ben Stiller’s Night at the Museum movies, or if you need a more reputable example, the Nabokov short story “A Visit to the Museum”). Corbett Lyon’s response to this was that the family are at ease in the place, because unlike conventional museums, it is always possible to look out. The housemuseum’s connections to the wider world are always evident, and not just in abstract, graphic gestures. It is in its fenestration and orchestration of connections that the Lyon housemuseum is least museum and most house. It is through simply being able to look from one space to another, to the garden, and past the property’s boundary fences to the context around, that the enclosure of the museum is undone. Permeability – between museum and domesticity, public and private, one building type and another – is elegantly achieved.

Details of Corbett Lyon’s custom-designed organ. Image: Dianna Snape

View across the courtyard to the music room and gallery space. Artwork: Patricia Piccinini, Panel Work, 2000 (wall); Peter Hennessey, My Lunar Rover (you had to be there), 2005 (foreground). Image: Dianna Snape

The Cotham Road elevation, again showing the overscaled letters detailed in the brickwork. Image: Dianna Snape

Callum Morton speaks about the lived experience and the complexities in opening a home to the public.

When Corbett and Yueji first talked about and showed me images of their housemuseum, it seemed, in the best possible way, a strange idea. There are of course many notable examples of private art collections in residential spaces that open to the public after the death of the collectors. These include Sir John Soane’s Museum and The Wallace Collection in London, The Frick Collection in New York, Peggy Guggenheim’s house in Venice and, locally, John and Sunday Reed’s house at Heide. More recently we have seen private collectors of contemporary art who have opened their collections to the public in spaces that mimic institutional ones – Saatchi Gallery in London, the Rubell Family Collection and the Margulies Collection in Miami, François Pinault’s Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice. But what Corbett and Yueji have done shifts this paradigm – they have allowed the public and the private to coexist simultaneously, opening their collection and their house to us while they are living in it.

Sounds simple, I suppose, but imagine for a moment that it was your house. Imagine you were having a bad day and a group of unruly schoolkids arrived at the front door. The family’s lives are as much on show as the work is. I didn’t know Corbett was a fine organist, and I must admit that since discovering this I have developed a rather contemporary Gothic image of him – dressed in a velvet robe, seated at his custom-designed organ, playing, perhaps, Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor. Suddenly he throws his head back and lets out a wild cackle that descends up the scale and echoes across the suburban neighbourhood. One might ask: Is Corbett Lyon the Vincent Price of Kew?

The distinction between public and private space is a rich subject and tells us much about how societies are working and developing. We understand more clearly now the nature of non-places like airports, cinemas, stadiums, freeways and casinos, to name a few – spaces that are neither public, in the sense that we feel an ownership over them, nor private – and have seen the emergence of deeply paradoxical spaces like the World Wide Web, which gives us access to an enormous public community from the comfort, and indeed isolation, of home.

This house is equally paradoxical. It is private mostly and public some of the time. We understand when we are here that the house is open to us as an invited public but that its essential condition is to be lived in by a particular family, so the codes of behaviour are unsettled. This discomfort is rendered palpable when we are upstairs and our eyes shift from the white cube below us to the bedrooms across the galleries’ breach, in an almost voyeuristic interplay.

In keeping with this paradoxical state the building fuses institutional and residential types. It is a piece of experimental architecture as well as a sociological experiment. We can sense here the influence of one of Corbett’s mentors, Robert Venturi, in the eclectic marriage of architectural types. The elegant black shed looks for all the world like a stealth bomber landed in the neighbourhood, with the Modernist white cube at the heart of the block and the black cube down the back. The white cube defines the plan of the house and we are always circulating around it, but out of this heart it gets messier. The collection spills into hallways, living rooms, dining rooms and bedrooms. The first works are hidden inside a cupboard, there are custom-made recesses to accommodate specific works and timber-panelled walls are textually inscribed with a potpourri of memories, places and names.

What is achieved here, outside of the marriage of spatial types, is something that a more conventional public space would find difficult to reproduce, and it is what makes the housemuseums mentioned earlier so enjoyable. Because the intimacy of the home is retained, we feel we are in an idiosyncratic, purpose-built wonderland of Australian contemporary art.

I imagine that most artists want to be collected. It affords us more time to work; it makes us feel we belong, that we are regarded. Who collects our work is not something we can easily control. But we do hope, at the very least, for collectors who are engaged by what we do – who, put simply, just GET IT. Add to this collectors who are as ambitious for their collection as an artist is for their work, who don’t think of investment in economic terms but in cultural ones, and you have an ideal marriage.

In Corbett and Yueji this ambition is manifested in the house. The narrative of the collection today illuminates an idea that has developed slowly from work to work, growing organically from the acquisition of the first work, Linda Marrinon’s Nude in a Landscape (1989), to the most recent acquisition of Kathy Temin’s My Monument: Black Cube (2009).

I think I speak for many artists when I say how grateful we are to see our work in a collection that displays such commitment to what we do. It’s a model which I hope will have far-reaching influence in sustaining the support for contemporary visual arts, both privately and publicly.

This is an edited transcript of a speech presented by Callum Morton at the opening of the Lyon Housemuseum, 20 September 2009.

Products and materials

- Roofing

- Alucobond.

- Internal walls

- Custom-fabricated timber panels; Boral plasterboard.

- Lighting

- iGuzzini low-voltage lighting.

- Kitchen

- Miele dishwasher and microwave; Viking stove and oven; Kleenmaid coffee machine; GE Monogram fridge.

- Bathroom

- Grohe tapware and fittings; tiled surfaces.

- Heating/cooling

- Mitsubishi fully ducted airconditioning; hydronic panel radiator heating.

Credits

- Project

- Lyon Housemuseum

- Architect

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

Marshall Day Acoustics

Audiovisual Urban Intelligence

Builder LBA Construction

Cost consultant Slattery Australia

Electrical consultant Umow Lai

Furniture fabrication Xilo

Interior design Lyons Architecture

Landscape consultant Lyons Architecture

Lighting consultant Lyons Architecture

Panel lining fabrication and specialized joinery Mortice & Tenon

Polished concrete flooring LBA Construction

Structural consultant Bonacci Group

Town planning Urbis

Zinc cladding Academy Roofing

- Site Details

-

Location

219 Cotham Road,

Kew,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Suburban

Building area 1060 m2

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 60 months

Construction 24 months

Website lyonhousemuseum.com.au/concept

Category Public / cultural, Residential

Type Culture / arts, New houses

- Client

-

Client name

Corbett Lyon and Yueji Lyon

Website Lyon Housemuseum

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 2010

Words:

Paul Walker,

Callum Morton

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2010