“Hank-n-Julie.” That’s how I’ve known them since 1976, always a pair and always in that order, even though that order is probably patriarchal – Julie was always the more vocal one. They were a power team even back then, part of a group of energetic graduates who made the Melbourne architectural scene of the late 1970s a time of significant change. With other always-pairs, Steve-n-Ro (Ashton) and Howard-n-Poh (Raggatt), they were part of a close-knit gang of students from the University of Melbourne and RMIT University. We all had cars that needed fixing, lived cheap and followed George Hatzisavas’s guide to ethnic cheap eats in inner Melbourne: Turkish Pizza, Lebanese House, Stalactites, the Waiters’ Club and Twins.

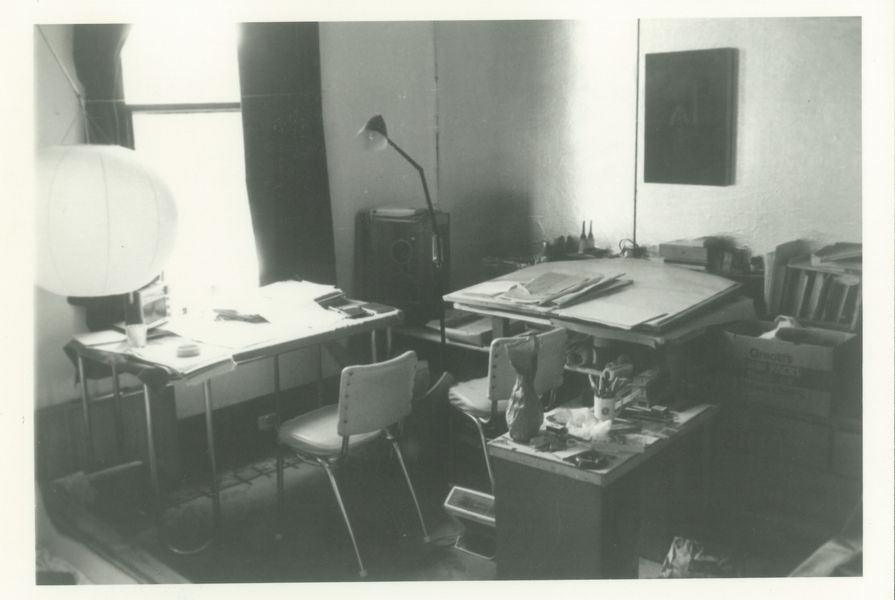

I met Hank around 1977, when we were both working for Max May. He was a laconic smart alec; irreverent, wiry and intelligent, he was a good foil to me, the garrulous smart alec. There was some considerable rivalry between us that I think Max enjoyed. It was not antagonistic, but pronounced enough for us to resolve an architectural discussion by wrestling it out on the straw matting of the old factory floor at 10 Peel Street in Collingwood, where Max had his office. We worked together on the project known as Toorak House in Russell Street. It is planned in the characteristic May way (a hierarchy of spaces, ordered for openness, function and privacy, all arrayed around a private courtyard), although the design has sections that May didn’t repeat in later projects. In particular, there are some PoMo moments: a faux ruined wall and rockery, a little rustic brick pavilion covered in creeper and embedded in the sleek modern glass frontage, a miraculous Vierendeel truss that hangs out on one end, apparently unsupported, and even a couple of classical columns in the garden. Jennifer Taylor refers to the house in Australian Architecture since 1960 as being “saved from pretension by the expressed humour” in the design. “It is a commanding building … yet its large size is belied by the lightness of the architecture and its magical transparency.” <sup1 It’s a Max May design, but the waggishness, the neat detail and the counterplay of finesse and anti-perfection display the Hank I know. The little brick hut might have been such a conceit, but it is beautiful.

Melbourne in the late 1970s felt a bit grim. Work was thin after the oil crisis and stock market crash (1973–75). Into the ‘80s Melbourne felt suspended, going nowhere, barely holding onto its St Petersburg self-identity and despairing that it was all happening in Tinsel Town Sydney.2

The architectural values of 1970s Melbourne were founded on the principles of English Brutalism: social activism, functional zoning around a sense of communality and unpretentiousness, simple blocky forms and rawness. Jackson Walker and Gunn Hayball were the guiding-light practices, with Kevin Borland and Peter McIntyre the architectural elders. Around this group was an emerging generation: Max May, Peter Crone, Cocks and Carmichael and Greg Burgess, but also Williams and Boag, Peter Elliott, John Kenny, John Baird and Peter Sanders.

Hank worked for Max. They shared an interest in both cars and in architecture characterized by a sensitivity for the craft of fabrication, in inventing ways to make things, and in gadgetry and pragmatics that could be artfully resolved. They and others in this circle of architects resolved design through systemized planning, a frugal vernacular of materials and adroit builderly techniques. Julie worked for Jackson and Walker and had an affinity with Evan Walker’s work and activism. In 1976 Jackson and Walker won an award for the low-rise, mixed-use housing development, City Edge, in South Melbourne. The project proved that you could build mass housing that would fit in with the existing urban fabric and incorporated community facilities (in this case, a kindergarten, a creche, a shop and a garden setting) without resorting to Commission towers. It is interesting to view Koning Eizenberg Architecture’s Los Angeles housing projects, and the practice’s social agenda, in relation to this period of Melbourne architecture.

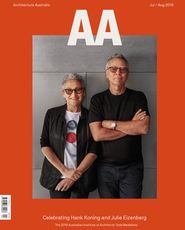

Julie Eizenberg and Hank Koning.

Image: Matthew Momberger

The Brutalist lineage is a stream of Melbourne architecture that is outside the “discourse and meaning” tradition, and therefore one that is discussed with less frequency these days. The award-winning projects of the 1970s were groundbreaking in typology – existing buildings were reused, houses were built on “unusable” blocks, and projects advocated for community, heritage and environmental values. Form was not the focus. To their architects, the projects’ forms would evolve through planning and making, albeit through an acute eye to the modernist style. Forty years later, in an article for Metropolis, Julie was quoted as saying, “ … the actual form plays second fiddle to the journey, or the experience.”3

The focus of the decade was on change, in design and in projects, for an equitable community. The circle even attempted to create a new Society of Architects, an alternative to the grey-suited club of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects. Hank and Julie were there when all the progressive practices got together with commentators and politicians from the left (and even Peter Davey, an editor at UK magazine The Architectural Review) to establish a new Institute, a now famous night of failure at The Last Laugh Theatre in 1979.

For their final-year thesis, Hank, Julie and Steve Ashton undertook a study of the history, potential retention and reuse of Melbourne’s remarkable nineteenth-century buildings of Collins Street, with a particular focus on the Rialto precinct. At the time, the street was marked for major demolition, which threatened the loss of important architectural gems, destruction to the fabric of the street and eradication of the lane networks. Their studies coincided with the rise of the radical Collins Street Defence Movement, a group of architects, politicians, academics, historians and the National Trust, founded and chaired by Evan Walker. Hank, Julie and Steve were key sources for the movement’s information and rhetoric. This was Julie in her element; diligent, frank and courageous, she could argue on point intelligently and without belligerence.

It is hard to convey the mood of this period. The end of one’s university years and the early days working as a young architect are formative for all, but I think the zeitgeist of the 1970s was particularly influential. The architectural scene was hungry for change, had a deep interest in the city, possessed a strong humanist social agenda and was energized by activism. I recall how articulate Julie was about these issues, and how deeply she thought about such things.

Hank, Julie, Steve and another University of Melbourne architecture student, Peter Craig, lived the share-house life in Cardigan Street, Carlton. Steve, like Hank, had a passion for cars and ways of making them work better. Hank was a bit of a boy-racer, and he was pretty handy with tools. Peter recalls this trait, accompanied by Hank’s inability to sit still, causing constant dusty renovation activity to their rented house. Unknown to the landlord and without permit, he would jump up, armed with a sledgehammer, and remove another bit of wall. He installed an indoor toilet and retiled the kitchen floor. He had that energy and set of skills of a fixer, the craft(y) builder. Hence the empathy with May.

The group of University of Melbourne friends included Grant Marani, the instigator and driving force behind the Halftime Club. The Club, which began in 1979, was an opportunity for graduates and students to gather in a local pub to argue about architecture, seek meaningful analysis of work and quiz invited, established practitioners as they presented their latest projects. It was a further flowering of the milieu, driven by that same mood for change – inquisitive, activist and discursive. However, it was different to the Brutalist lineage. The older group didn’t talk about how they designed or about their strategies or influences, but rather mostly about function and social action. On the other hand, Halftimers had a strong formal focus aligning with the “discourse and meaning” stream that was emerging in Melbourne – curated by Peter Corrigan. Hank and Julie were there at the Club’s invention and were founding members.

And then, Hank and Julie left Melbourne to study at UCLA. They left as graduates, completed their masters, became friends with their professors, the late Bill Mitchell and Charles Moore, became neighbours to Frank Gehry, set up shop and had two sons. It’s something many graduates do, go away, and there’s no single reason why. Some leave because it’s the thing you do for adventure and opportunity, while others leave to escape the claustrophobia of a small community, to expand one’s vision. They kept in contact with chums back in Melbourne, but some of the chums got aggro when Hank and Julie visited to show their studies into algorithmic design process. The chums were pissed that they had abandoned the local fight.

But, of course, they didn’t give up the good fight. They weren’t like that. They went and created a remarkable, multi-awarded practice of nearly forty years, and an important culture of civic engagement and architectural education that few Australian practices can match. They have produced signature work, groundbreaking projects in adaptive reuse, for not-for-profit organizations and in affordable and cooperative housing. And they have a span of museum, educational and high-profile commercial projects on their awards list, too. Additionally, Julie has become a lifelong educator, a leading teacher and lecturer in theory across the USA. Back in Melbourne she is a regular contributor at the University of Melbourne.

It’s interesting to see them referred to as “quintessentially southern Californian” architects, because I see their work through the Melbourne traditions of their early development. The things that happened and the beliefs and ways of thinking in Melbourne architecture at that time set their spirits alight. Crafted, economical, inventive and carefully planned for function and space, their projects are not focused on capital “F” Form or capital “N” Narrative but rather on the clever resolution of the specifics of each project. And there is always that sense of vitality and lightness in a city so very different from here. I see Melbourne. They’re in the family. They moved to LA forty years ago, but Hank never lost his accent nor Julie her sense of inquiry and action. And neither lost their sense of humour.

— Ian McDougall is a founding director of ARM Architecture and adjunct professor at RMIT and the University of Adelaide. He was there when all of this happened.

Author’s note

With thanks to Max May, Peter Craig and Grant Marani.

Footnotes

1. Jennifer Taylor, Australian Architecture since 1960 (Law Book Company, 1986), 216.

2. These terms were used by Meanjin editor Jim Davidson to describe the Melbourne–Sydney rivalry. See Jim Davidson, “St Petersburg or Tinsel Town? Melbourne and Sydney: Their Differing Styles and Changing Relation,” Meanjin vol 40 no 1, April 1981.

3. Christopher Hawthorne, “The Right Touch,” Metropolis , 1 December 2011, metropolismag.com/architecture/the-right-touch/ (accessed 6 May 2019).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 29 Oct 2019

Words:

Ian McDougall

Images:

Matthew Momberger

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2019