Creatively directed by Sandra Kaji-O’Grady and John de Manincor, and held at the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre, the 2013 National Architecture Conference explored the theme of Material. It asked questions like, “Is fog an architectural material?” “What would a brick answer to a robot that asks, ‘What do you want to be?’” and “In the wake of asbestos, what scope is there for architects to experiment with new materials?”

The conference website stated: “The materialisation of built form is but one strand in the complex web of our discipline. Architecture’s material presence weaves around individual experience and defines the fabric of the city. The 2013 Conference will explore contemporary applications and ideas surrounding material in architecture.”

Kaji-O’Grady and de Manincor elaborated on this broad agenda on the first morning of the conference by recalling the late 1960s conceptual art of Robert Barry, whose sculptural materials included inert gas, radio waves and telepathy. This reference underlined the directors’ interest in fringe interpretations of material, a natural continuation of Kaji-O’Grady’s early-noughties research work into meat and architecture. Thus widened, the scope of the conference looked well outside the familiar: mud, pollution, air pressure, plastic hose and windmill blades were a few of the materials presented in the two days following.

What did I think? Aiming to “avoid fixed styles in the selection of presenters,” Kaji-O’Grady and de Manincor assembled a heterogenous group of speakers, from Matthias Kohler’s research into robotics, to Kathrin Aste’s sublime interventions in steel and concrete, to Cesare Peeren’s radical approach to upcycling. The collective presentation material cannot be said to lie along a single gradient, though fellow delegate, Sarah Herbert, made this valuable offering. Instead, we felt that three clear themes emerged to both align and distinguish the speakers’ areas of interest:

New technologies: Billie Faircloth, Virginia San Fratello and Jorge Otero-Pailos (USA), Jose Selgas (Spain), Philippe Rahm (France), and Matthias Kohler (Switzerland).

Sustainability: Cesare Peeren (Netherlands), Emma Young and Tim Greer (Australia).

Aesthetic form: Yosuke Hayano (China), Carey Lyon (Australia), Manuelle Gautrand (France) and Kathrin Aste (Austria).

What was evident was the contrast between Australian and international speakers. As might be expected from a conference aiming to exhibit ideas and individuals unfamiliar to its audience, the bulk of the speakers were international. Inevitably, though perhaps unintentionally, the Australian representatives in Young, Greer and Lyon embodied the classically Australian practice of research through built work. They communicated a gritty determination to build first and extract architectural intelligence second, a frequent side effect of the wealth of construction opportunities in this country.

It might be argued that we would benefit from the considered resourcefulness of the Europeans, as displayed by Peeren’s repurposing of windmill blades as play equipment, or the scholarly exuberance of the Americans, as conveyed by Otero-Pailos’ development of scents for Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Certainly, the presentations of Young, Greer and Lyon had far more in common with China’s Hayano (who, with MAD Architects, builds large and fast and often) than they did with their European or American counterparts. However, this regional association might not be such a bad thing: on the one hand, the hurdles of finance and construction diminish the possibility of truly radical ideas, yet on the other they permit an evolving dialogue between design, theory and the built environment. A subject for a future conference, perhaps.

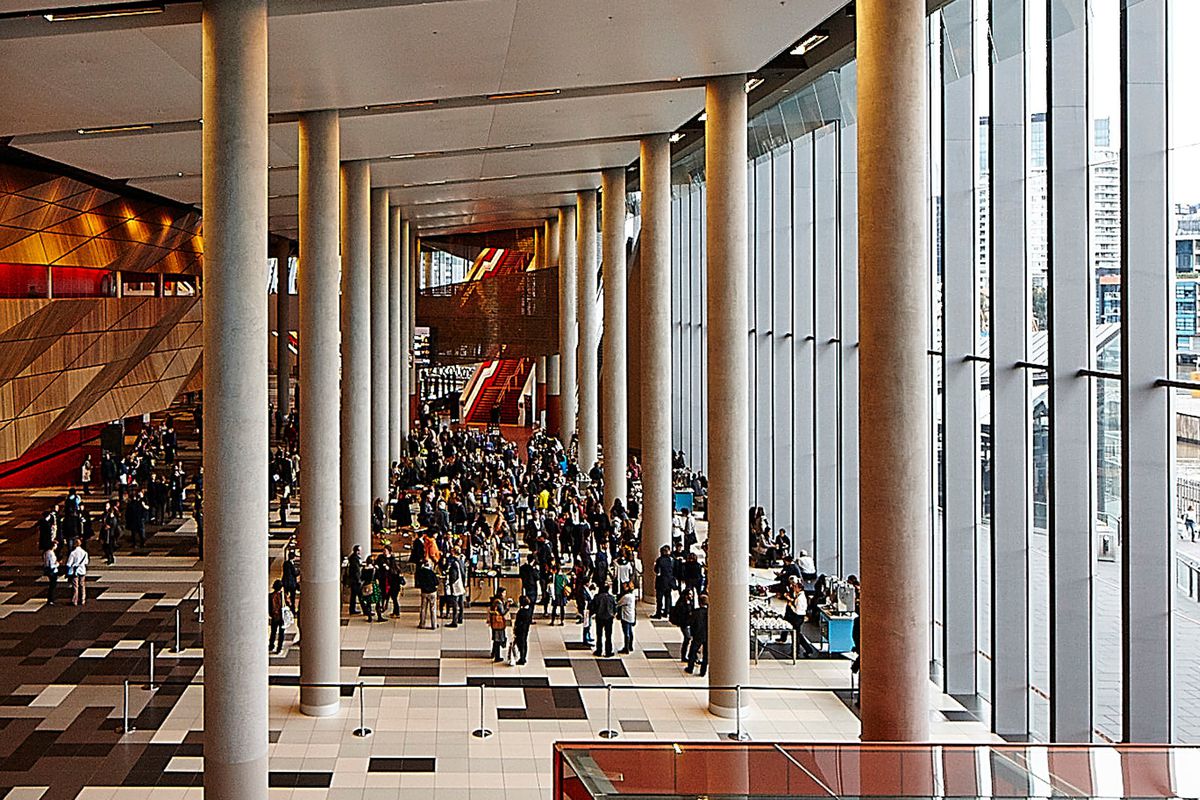

The lecture theatre fills on day one of the Material conference.

Image: Warwick Mihaly

To my mind, only a few of the speakers were as persuasive as the best speakers at the World Architecture Festival (WAF) I attended in 2010: its focus on urban renewal continues to resonate. Unfortunately, I suspect this was as much a reflection on delivery as it was on content. A worrying number of the speakers ignored the first and most basic rule of design communication: Show it, don’t say it. The worst offenders were Faircloth, whose rapid speech rate at times made her unintelligible, and Rahm, whose data-heavy slides were repetitive.

In stark contrast, San Fratello was captivating, a seemingly unanimous audience favourite. She discussed some of her practice’s delightful small building work before dipping into her more recent interest in 3-D printing. She wove stories around each project, unpacking their ideas, processes and executions: the homeless man whose first, negative reaction to Sukkah of the Signs gave way to advocacy; or the recycled glass tubes in SOL Grotto whose combined market value of half a billion dollars made it the most expensive art piece ever. She spoke a lot about materials, as well as contexts for their use: the ideas for the temporary Straw Gallery, whose gestation tracked through two other projects, and whose hay bales were ultimately returned to the farm from which they originated.

Selgas, Peeren, Young and Aste were also stimulating. Together with San Fratello, they each presented fascinating projects, and were able to communicate their essential qualities while also addressing the conference subject. This is not to say that none of the other speakers presented interesting ideas, only that their presentation styles failed to fully engage. Though Paul Finch managed to do it at WAF, it is difficult to suggest how this might be systematically avoided: I suspect Kaji-O’Grady and de Manincor wanted to host speakers from whom they had never heard, uncovering interesting architects without knowing for certain that they could perform in front of an audience. They did take a tentative step towards thematic integration, with most speakers sharing paired lecture slots to highlight common investigations. This could have helped break into the content of prepared lectures and initiate cross-examination of ideas. Unfortunately, it proved to be little more than a scheduling device as negligible opportunity was provided for the speakers to respond to, or critique, one another’s work.

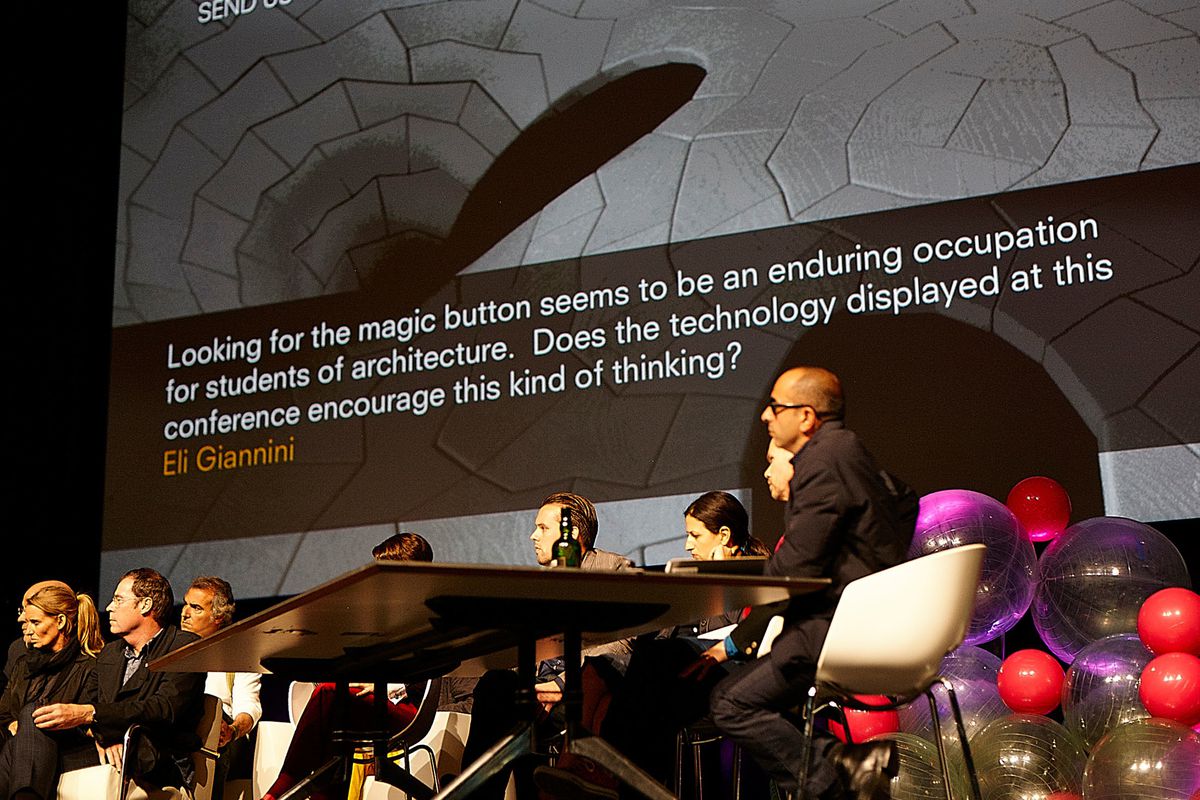

Kaji-O’Grady and de Manincor explained that in order to accommodate all twelve speakers within the two days, inter-speaker conversation and question time were to be limited to a single discussion panel at the conclusion of the conference. They invited delegates to relay questions for the panel via Twitter and SMS, a clever idea that encouraged #material2013 related commentary. The panel, hosted by the academic Nadar Tehrani, was wearying and managed to ignore all but two of the delegates’ generally excellent questions, which were displayed on the big screen behind the panellists, scrolling by as the discussion panel studiously ignored them.

Participants took in the views over lunch in the foyer.

Image: Peter Bennetts

What did we learn? Attended by around one thousand architects from around Australia and across the Tasman Sea, the conference is the most substantial national event run each year by the Australian Insitute of Architects. Its value lies not only in attending the lectures, but in discussing the merits of their content with both old colleagues and new. Over the course of lunch or evening drinks, indecipherable presentations were reinterpreted with new meaning, glamorous presentations were deconstructed into trivialities, and banal presentations became contentious.

Rahm’s lecture was an example of the former. It may have been mis-aimed, but the ideas behind it – of an urban environment scientifically tailored to counter undesirable climatic conditions – were worthy of lengthy discussion. Gautrand’s lecture on the other hand exhibited a succession of beautiful forms and playful textures, which upon closer examination proved to be without context or reason. And finally, Kohler’s lecture on robotics appeared to be interested primarily in the sensational, but managed to divide the audience between those who saw him as wasteful and those who saw him as a visionary.

Personally, I would have liked to hear from architects who are unequalled in their ability to direct craftsmen in the use and execution of physical matter, who, like Le Corbusier, “can control tonnes of concrete like an artist controls tubes of paint.” Given his recent Pritzker Prize, Toyo Ito might have been a big ask, but Peter Rich of South Africa or Brian MacKay-Lyons of Canada would have offered meaningful voices to this complex subject.

It is immensely gratifying that the role of creative director for these conferences is so highly sought after, attracting individuals of such diverse and productive interests, and I congratulate Kaji-O’Grady and de Manincor for what would have undoubtedly been an organizational task of mammoth proportions. Overall, the 2013 National Architecture Conference boasted many satisfying hits and only a few misses. Intellectually and socially, it was a great success, and I especially enjoyed meeting, face-to-face, other architects whom I had previously only known online. That such a community can exist despite the divide of geography is testament to shared passions and the hypermodern world of communication.

This was my first National Architecture Conference, but it will not be my last. The 2014 conference, to be directed by Adam Haddow, Helen Norrie and Sam Crawford, will be held in Perth (for the first time in a decade) and explore the theme of “Making: the dirtiness, directness and honesty of architecture.” I’m excited by the chance to visit the west coast and attend a conference whose theme might speak to our own interests in architecture.

Can’t wait!

Edited and reproduced with permission from Panfilocastaldi. Other coverage of the 2013 National Architecture Conference here.