<b>REVIEW</b> GINI LEE <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> TREVOR FOX

East elevation of Phillips/Pilkington’s McCormick Centre for the Environment in Renmark, SA.

Meeting room in the south wing, which contains the working areas.

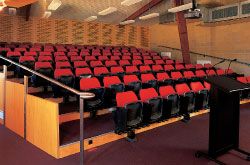

Lecture theatre.

The interactive display by EmeryFrost, in the north, public wing.

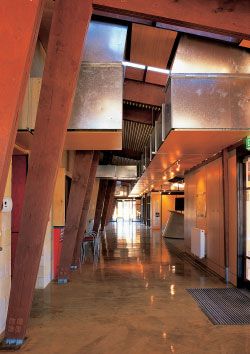

View along the public circulation spine. The building is detailed so that functional elements also have spatial and decorative effect. Here the roof cooling system extends into and articulates interior space.

South-west elevation.Water tanks and other services are located along the southern side.

West elevation.

East elevation. The two wings are distinctive in function and appearance.

Verandahs on the north wing accommodate public gatherings.

PHILLIPS/PILKINGTON ARCHITECTS’ McCormick Centre for the Environment in Renmark in the Riverland of South Australia is defined by a specific attitude to the ethics of architectural practice. Unself-consciously designed around ecological principles, it pays close attention to the sustainable systems that generate its form and scale. It sits apart from the surrounding rural, vernacular landscape, while also exploring a regional approach to contemporary rural architecture, that of the expanded shed.

The project is an architectural outlier, and through its presence it exposes the consistently unimaginative and unresponsive building and landscape development that characterizes country towns all over Australia. To the locals, it’s a bit different. The lady in the local pub directed us to it, “Head out of town, love, over the bridge, past the old school and look to your right – you can’t miss it!” To the international sponsor it looks like his idea of an “Australian” building; it has indoor/outdoor spaces with verandahs. Such comments suggest that the centre is achieving one of Sue Phillips and Michael Pilkington’s aims – to demonstrate that contemporary architecture can enable ecologies of local identity through expressive building type, form and materiality.

A strong commitment to the environmental restoration of the River Murray and its wetlands led the clients – the Australian Landscape Trust and the Renmark Paringa Council – to conceive this project as a place where various visitors, researchers and the local community could find the space to gather, learn and experiment in wetland systems research. In seeking out and winning the commission for the building, Phillips/Pilkington drew on their interest in making pragmatic and thoughtfully detailed buildings that demonstrate the possibility of responsive architecture in rural contexts.

Designing and managing an ecologically oriented building to completion is a challenging task. Often the most difficult part of this complex process is ensuring that the original vision of the client and architect continues beyond the initial concept and costing proposals. In the McCormick Centre, shifting priorities and site availability resulted in a change of focus from a predominantly tourist centre overlooking the River Murray to an educational facility with a small tourism component. Starting out as the front door for the Bookmark Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO-recognized project and site, the centre was subsequently relocated on a landlocked former education department property further out of town. Here the demonstration environmental infrastructure and wetland regimes needed to be conceived and implemented from scratch.

Despite these brief and site changes, Phillips/Pilkington managed to sustain the ecological agenda. Their tenacity in advocating an ESD approach was matched by the client’s significant role in formulating briefs with sufficient complexity and flexibility to achieve new building types based on an ecological ethos. Client advocacy is crucial to the development of responsive and sustainable architecture, and this support must extend into the ongoing promotion of experimental systems and forms that do not always result in buildings that future occupants expect and can manage.

The Renmark building is a functioning and a conceptual laboratory. Underpinning all of Phillips/Pilkington’s work is the intent to respond to the particularities of locale, and to produce a resulting net gain to the environment – gains that can be achieved through effective energy systems, or through an architecture that demonstrates attention to scale and materiality within regional aesthetic and political agendas. The architects consider the McCormick Centre to be the most resolved of their tourism and community projects. Here the sustainable systems trialled in the Monarto Zoological Park Visitors Centre (1997) and Innes National Park Visitor Centre (1999) have been revisited and refined. These first buildings were prototypical “green” buildings, where systems were developed and implemented, successes revisited, mistakes made and rectified. Through these projects, Phillips/Pilkington created a research and development methodology to inform their architecture, such as is achievable within the limited resources of small-to-medium private practice. The result is the evolution of an architectural programme that adopts an informed experimental approach to the trialling of energy systems in conjunction with effective orientation, planning and sustainable material selection.

Outwardly, the building is an expanded shed on a flat site surrounded by a disused school site, grape vines and assorted houses of the kind that are often found on the periphery of country towns. Two linear, functional wings are hung off a highly visible, east-west-orientated central masonry wall, a spatial and a structuring device that operates as an effective thermal sink. The north-facing public and display areas include interior multipurpose spaces, an interactive display by EmeryFrost, a teaching laboratory, and two large verandahs intended for public gatherings. Views over the associated wetlands, popular with local birdlife, are mediated by narrow, vertical fenestration, which provides the low, flexible lighting levels required for audiovisual and exhibition purposes.

The working areas of the building are located on the south, including services, a lecture theatre, offices and the service yard.Water collection tanks, access roads and other back-of-house functions are all sited along this southern side, and are clearly visible from the road. By presenting this service aspect to the arriving public, the building shows that business is going on. Yet subsequent management of public access and landscaping has not served the public face of the building well. The combination of north-south orientation and public road systems means that visitors tend to arrive at the back door. This is a pity, as the care taken on the northern and end elevations to articulate structural systems and forms, alongside photovoltaic power generation arrays on the roofscape, provides the most effective public views of the building’s intent, and these can be missed.

Phillips/Pilkington regard this project as a rugged compromise. It has been shaped by the reality that in everyday working situations the desire for innovative technologies is, in the end, tempered by cost-management regimes and the vagaries of local climate.

A case in point is the air-cooling system. The passive system designed specifically for Monarto had to be redesigned to suit dry conditions and a hands-off management regime. A more sophisticated yet more conservative and active system was developed for the McCormick Centre. This follows similar design principles and uses commercially available evaporative cooling, with fans powered by a photovoltaic closed cell system, resulting in a more robust system that returns power to the grid for most of the year.

The McCormick Centre is designed with economic construction in mind, including minimal material use with a focus on Australian product. Materials and finishes have been selected and detailed to afford decorative possibilities, alongside robustness, fitness for use and simplified construction processes. In keeping with this interest in detailing that expresses both functional intent and decorative possibility, the highly visible roof cooling system extends into and articulates interior space in the public circulation spine. Along its length, a raised ceiling, suspended cooling system and exposed galvanized ductwork is reinforced by Hoop Pine plywood panelling to bulkheads and walls. The panelling extends a kit-of-parts approach initially trialled at Innes.

Each detail of the McCormick Centre demonstrates a concern with sustainable and ethical practice. But how effectively can buildings convey the complex message of sustainability? For the architects, the green initiatives have finally all worked in this building. Yet it has taken a number of years and a number of projects to achieve what is, for them, a workable solution. Phillips/Pilkington’s design work demonstrates that architectural practice is about acquiring knowledge through doing. Their suite of buildings confirms that doing it over and over again, and not giving up on experimentation and research, will ultimately deliver rigorously conceived and executed buildings. Along the way, they have also defined a very personal attitude to an ethics of architectural practice.

GINI LEE IS A LECTURER AT THE LOUIS LAYBOURNE SMITH SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA.

Project credits

Architect/interior designer Phillips/Pilkington Architects— project team Michael Pilkington, Susan Phillips, Nigel Miller, Amy Hallett, Matt O’Brien, Craig Buckberry. Client Australian Landscape Trust and District Council of Renmark and Paringa. Landscape architect Hilary Hamnett & Associates. Quantity surveyor Rider Hunt Adelaide. Structural engineer John Bowley Consulting Engineer. Civil engineer MCE Consulting Engineers. Mechanical and electrical engineer Bassett. Hydraulic engineer Connell Mott MacDonald. Builder Cox Constructions. Murray/Darling Basin model and exhibition design Emery Frost.