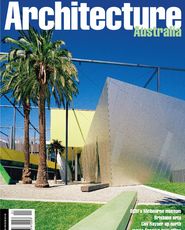

View from Nicholson Street. Image: John Gollings

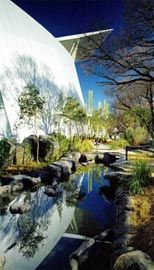

The Milarri Garden, with the Forest Gallery blade beyond. Image: John Gollings

The broad entry plaza mediates between the scale of the city and that of the museum. Image: John Gollings

The transparent principal entry facade. Image: John Gollings

Image: John Gollings

The neo-constructivist elements of the museum’s southern aspect. Image: John Gollings

View from the western edge of the Carlton Gardens. The colourful tilted cube of the Children’s Museum is to the left, with the Children’s Garden in the foreground. Image: John Gollings

Cafe courtyard. Image: John Gollings

Aerial view, showing the museum’s location in the Carlton Gardens and its relation to the towers of the Melbourne CBD. Image: John Gollings

The museum from the south side of the gardens. The central blade, on the museum’s north-south axis, shelters the Forest Gallery. Image: John Gollings

Approach from Nicholson Street. Image: John Gollings

Looking along the upper circulation gallery, to the eastern end. Janet Laurence’s installation, Stilled Lives, is in the foreground. Image: John Gollings

The main public promenade and suspended blue whale skeleton. Image: John Gollings

The exhibition Te Vainui O Pasifika in the Te Pasifika Gallery. Image: John Gollings

Entrance foyer with Patsy, a 1929 ’couta boat. Image: John Gollings

Wurreka by Judy Watson, in the entry to the Kalaya Meeting Place. Image: John Gollings

Looking through a “black box” exhibition space to Te Pasifika. Image: John Gollings

Interior of the Kalaya Meeting Place, part of Bunjilaka, the Aboriginal Centre. Image: John Gollings

Museums are not what they were. While they have become much more exciting places to visit – architectural bravura has played a large part in this – the raison d’etre for their massive collections and their display and conservation traditions has become less and less apparent. They face ethical dilemmas over what these collections are for and what they represent. And even over who really owns them. At the same time, the role of the museum beyond collecting and conserving has become diffuse.

Museum research in “natural history” and ethnology was long ago overtaken by universities, and the institution’s traditional commitment to public education looks likely to be replaced with infotainment as it responds to pressures to demonstrate relevance – by getting as many people through the doors as possible. The concept of amenity and education as public investments has been usurped by a reduced view of these things as private goods.

It has been hard, in these circumstances, for the old urban dialogue between distinct public and commercial architectures to continue. This dialogue once defined the symbolic realm of the central city. Major urban interventions of recent years in Melbourne, at least, have blurred these differences, just as the territorial specificity of the central area is blurred in the ongoing CBD expansions south of the Yarra and those planned west of Spencer Street.

Denton Corker Marshall’s design for the new Melbourne Museum responds to these issues of institutional purpose and public profile – and turns them to strategic significance. In some regards spectacularly. The building re-asserts a role for public architecture in distinguishing the central city, for example. It clearly enjoys a site which makes this possible, on the slightly elevated rim that half encircles central Melbourne on its northern and eastern flanks and then runs down William Street. This rim, as the architects realised, links the site to that of the

courts, Melbourne University, the hospitals on Victoria Parade, and the State Parliament and Treasury buildings – other places of strong, if now compromised, public significance. The old Exhibition Buildings (now in the museum’s care) used this locational advantage. Their dome, as historian Paul Fox points out, answered several other domes on public buildings in Melbourne elevated by topography or by tower (Architecture Australia, June 1990). The long front wall of the museum building in effect forms a city wall to reinforce the older architectural marking of the place. It makes a new northern boundary for the extended CBD beyond the Hoddle grid.

The slight elevation of the museum site and the depth of space across Carlton Gardens to Victoria Parade have offered an opportunity to look back from this wall to the city, seen principally as the eastern cluster of downtown commercial towers. The large museum plaza – too big to serve only as a forecourt – mediates between the urban scale and that of the building. The sense of the city as spectacle is further emphasised by the two roof blades that hover above the facade, diagonally framing the Exhibition Buildings opposite and the views to either side. It is as if the largest artefact in the museum collection is not so much the Exhibition Buildings as the city itself. A third blade is lined up along the museum’s principal north-south axis. Tilted more dramatically, it is apparent, not from the city side but from the back, even visible several kilometres away along the Eastern Freeway’s approach to the central city.

The Melbourne Museum addresses the urban issues raised by its site and the typological history of the public institutional building. It also confronts internal institutional problems now faced by museums – the role of research for instance. On the day of the new building’s public opening, a short article appeared in The Age about the Melbourne Museum’s request for an increase in its operational grant which had been declined by the Victorian Government. The comments by a staff union representative that the money was needed to stop further reductions in the museum’s research efforts were probably read by few of the thousands drawn by free performances and by publicity pumped out by the same newspaper (a major sponsor).

Architecture cannot solve the problem of research in the museum. But DCM’s design has, at least, been acutely aware of it. Research is rhetorically privileged in the place.

Two big, sulphur yellow elongated boxes, housing a large part of the research collections, hang over the length of the main public circulation volume within the building, one either side of the centrally placed public entry. Offices for researchers and curators are lined up in rows in front of these storage boxes, with their glazed front walls just behind the glazed principal facade of the building. From the front, research and curatorship are somehow – if remotely – on display. It looks as if they count. But this arrangement is also a very practical one: the object and the agent of inquiry are placed immediately beside each other.

More important perhaps than the little flourish of idealism in the location and visibility of research accommodation is the careful orchestration, in the museum’s public areas, of circulation and exhibition, and the relation of exhibition zones to each other. Circulation areas are used in a limited way for display, especially for a few large iconic objects – a blue whale skeleton on the main public promenade, a ’couta boat complete with unfurled sail in the high slice of space at the front of the building.

A fantastic installation by artist Janet Laurence using specimen bird and animal skins, shells and minerals from the museum’s reserve collections currently occupies two vitrines in the upper level circulation spine. But in general the public areas of the building do not integrate circulation and exhibition into a single entity. Such integration was the strategy of many nineteenth century museums with natural history and ethnography collections – they often followed a putative evolutionary line in their spatial organisation of exhibitions. It is also a strategy that is increasingly used in contemporary institutions with an overweaning intention to tell a single determinate story with artefacts and architecture.

It is perhaps a pity that more attention to possible narrative (mis)readings was not given by DCM to their Melbourne Museum design. An unintentional relationship between infancy and indigeneity could be inferred, for example, in location of the children’s museum at one end of the complex and the Aboriginal centre, Bunjilaka, at the other. The curvy elements in the ceilings, walls, and walkways of the latter seem to imply a banal correlation of aboriginality and “natural” forms.

But generally the fragmentation, dispersal, and almost random connections between the various exhibitions galleries that unfold off the main spine seem about right. It has also facilitated break-out spaces to combat museum-fatigue, not only in the distinct circulation areas, but also in pockets of outdoor space – balconies, enclosed gardens, roof terraces – that the architects have captured here and there.

The galleries are generally of two kinds. Some are large “black box” spaces. In these the exhibition experience is fundamentally determined not by the architecture but by contrived (and in my view patronising and overly didactic) installations of artefacts, display materials, and information. A set from “Neighbours” – found in the Australian gallery – is not worth seeing outside a soap opera milieu this museum is not equipped to present. The architects are blameless in such choices of what to show. Indeed the best things in the black box galleries are the beautifully crafted display cases designed by DCM to give some order within all the visual and aural chaos. Museums currently think people like this mess. But when I visited, many other visitors were enjoying the decontextualised and ordered things in Janet Laurence’s vitrines. Some of the galleries will offer this kind of experience on a grander scale. A lofty white space currently contains an

exhibition of canoes from the Pacific with minimal interpretative clutter.

Another similar gallery – for dinosaurs – will open soon.

The fragmentation of the galleries allows the museum to try different strategies for different kinds of audiences, and to revise one exhibition without revising them all. This is important when the agenda of such institutions, no longer self evident, is subject to ongoing change. In this regard, the most problematic of the exhibition volumes is the Forest Gallery, the legacy of a previous museum director with experience in wild-life sanctuaries. It has anomalously installed a fragment of Victoria’s “natural” environment under the blade roof right at the centre of the building. Its trees and pools will be populated with birds, fish, snakes, insects. But DCM has even extracted some advantage out of this curiosity. Mesh walls and a steep blade outside the visitor’s angle of vision enable transparency to be extended right though the middle of the building from the glassy screens of the northern facade.

All of this is part of the neo-constructivist approach that DCM have become known for. Whatever we might think of this style, it is deployed in the design of the Melbourne Museum to make an instrument carefully honed

to the site’s urban potential and to the contingencies that all museums currently face. It remains to be seen whether this instrument will be played as well as it deserves.

Architect’s Statement

Museums Victoria presents the Great Hall and the new Melbourne Museum as a complementary pair. The museum is the dominant partner, bringing the buildings and gardens together as a “visually interdependent whole”, clearly linked to the city as one of its major institutions. But it will be an institution like no other – a building which opens up to reveal in a simple way the fascination and complexity of its purpose to all who visit. It is be confident and mature, elegant and visionary; a key Melbourne building for the next 100 years.

The museum plan uses a campus mode: an arrangement of varied elements grouped together beneath a formal volumetric framework that constitutes a reference to the formality of the site and even evokes a sense of the Hoddle grid – a Melbourne icon.

At 70,000 square metres, the museum is a much bigger complex than the Great Hall, but it takes scale references from the hall. The Great Hall establishes scale by detailed embellishment within a monumental form; the museum by articulated volumes within a detailed frame. Its elevated central “Gallery of Life” contributes to its status as a complementary building in the Carlton Gardens with power and strength of its own.

The enveloping grid framework is a significant element of the design. Its formal qualities allow the complex and varied elements with the “campus” to read as individual components; separate elements, or example, the research centre, the Imax theatre, or the Aboriginal centre, have greater individuality than would be possible or appropriate without the ordering frame.

It is a building that is also a collection of buildings, where the landscape interpenetrates the forms and where garden and open activity space interact. It subtly lays claim to a powerful presence by its very interaction with the landscape; the gardens themselves become inclusive to its form. It is not a forbidden and impenetrable institution entered through closed doors.

Denton Corker Marshall.

Credits

- Project

- Melbourne Museum

- Architect

- Denton Corker Marshall

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Certifier

Peter Luzinat and Associates

Landscape architect Denton Corker Marshall

Services engineer Lincolne Scott

Structural engineer Arup

- Site Details

-

Location

Nicholson Street,

Carlton,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Website http://museumvictoria.com.au/melbournemuseum/

- Client

-

Client name

Victorian Government Office of Major Projects on behalf of Museums Victoria.

Website majorprojects.vic.gov.au