MANDURAH WAR MEMORIAL

Overview of Mandurah War Memorial during a ceremony.

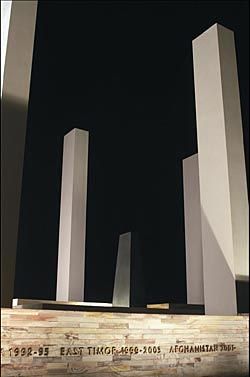

Looking along the main ceremonial approach. The “Eternal Procession” of pillars marches across the site along the axis of the rising sun on Anzac Day.

Water from the pool of remembrance weeps back into the estuary.

The pillars sink into the ground in a pohutukawa grove.

The memorial seen across the estuary. Photographs Hames Sharley.

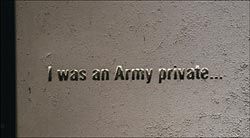

Fragments of an anonymous poem etched into the pillars.

The memorial offers a personal and reflective experience.

The towering pillars of the ceremonial space.

Looking over the plinths of Kimberley sandstone and Western Australian quartzite, with the estuary beyond. Photographs Des Birt.

Narelle Yabuka contemplates the Mandurah War Memorial, by Hames Sharley, which remembers all those Australians who have lost lives in, or been affected by, war.

The expression of personal memory is difficult, intimately embedded as it is with emotion, individual experience and degrees of perception. To express memory sculpturally or architecturally on a collective level would seem to be an even more difficult challenge, though one that is often undertaken. Further, the collective remembrance of wars and their massive, often anonymous, human losses may include a political component, and unavoidably flirts with the potential for the ideological shading of historical events.

Writing on his recently completed Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, Peter Eisenman remarks that ideas about both memory and monuments have changed. The Holocaust and Hiroshima, he writes, dissolved the certainty that an individual would die an individual death, which could then be commemorated with a single marker (a stone, slab, cross or star).

“[A]rchitecture can no longer remember life as it once did,” he cautions.

Similar challenges faced the architects from Hames Sharley’s Perth office as they designed the Mandurah War Memorial and their thinking oscillated between conceptions of the memorial as monument, place and space. The Mandurah War Memorial commemorates lives lost and damaged during all wars in which Australian forces have served and was the subject of a 2004 competition held by the City of Mandurah.

The memorial is located an hour’s drive south of Perth in one of the country’s most rapidly expanding “sea change” cities. Here, in a context of relaxed lifestyles and tourism, the memory of war becomes a journey to be experienced. Iconography and abstraction clash, encouraging fluctuations between mental, visual and bodily experiences of architecture, historical narrative and memory.

The memorial takes its place on a vast and prominent grassed site on the western foreshore of the estuary, around which life in Mandurah is largely organized. An artificial canal, leading to a waterfront housing estate, hems one long boundary of the site, with a car park, fairground and oval on the other.

The memorial’s primary formal elements are made of easily constructed and replicated white concrete pillars – a response to the powerful visual impact of repetitive headstones in war cemeteries in Europe and America, the small budget and the need to work at a significant scale.

En masse the pillars form an “Eternal Procession” that marches across the site along the axis of the rising sun on Anzac Day. Two and three abreast, the pillars rise from the estuary water to maximum height at a ceremonial space, before falling away and sinking into the earth amongst a grove of pohutukawa (New Zealand Christmas trees). The human scale of the pillars at the water’s edge clearly relates to imagery of soldiers storming a beach, just as the sinking pillars evoke headstones. Yet despite this iconography, the simple and constant geometrical pillar form also maintains an abstract disjunction from the site, and some degree of ambiguity.

Plinths of comparatively colourful Kimberley sandstone and Western Australian quartzite accompany the pillars on their ascent to the central ceremonial platform and a pool of remembrance, where two other pathways join. The more significant path follows the RSL’s preferred Anzac Day processional approach from the south-west, passing a garden of olive trees (peace) and rosemary (remembrance). The other path traces a trajectory between the car park and a public seat at the head of the site (surreptitiously installed by a local resident at his late wife’s favoured place of meditation). This confluence of axes, say the architects, creates “a focal point where the two marches meet – the procession of the living and the spirit of those who have passed.” ›› The pool water “weeps” back down to the estuary in a fracture between the pillars and plinths. A more direct narrative element appears on the pillars in the form of sandblasted fragments of an anonymous Australian war poem. Facing the rising sun, the fractured poem begins at the water’s edge, running along the procession of pillars and terminating with them in the grassed area. These fragments contain the reflections of an Unknown Soldier on the experience of “a landscape pockmarked with war’s inevitable litter” and “the chaotic maelstrom of Australia’s blooding”.

Procession and, by implication, ritual are at the core of military activities and of Anzac memorial services. Although functional requirements and siting issues necessitated the processional approach to the memorial, its configuration as a space for movement rather than settlement indicates that the body is a vehicle for the experience of memory here. Viewing and experiencing the memorial is likely to prompt a range of readings and impressions.

The enclosing arrangement of offset towering pillars and plinths has a confrontational effect, casting shadows, with gushing water nearby. However, there is also a calm visual satisfaction in the axial alignment of pillars of graduating height, fringed symmetrically by trees.

The spatial itinerary suggests ritual and the passage of time. The cycle of water and the path of the sun call to mind the cycle of life and death of the individual soldier, and the individual civilian. Pleasingly, the memorial’s most direct narrative element – the series of etched poem fragments – is perhaps also the most enigmatic, as for much of the day it lies in shadow. This degree of formal ambiguity presented by the memorial as a whole is fitting – the regular passage of pleasure craft on the water and the presence of picnic-goers on the site would perhaps jar with a more traditionally monumental or nostalgic memorial.

Though the space is communal, open to its site and visually prominent from the opposite foreshore, one’s experience of memory at the Mandurah War Memorial is personal and contemplative – as much a bodily encounter as a mental and visual one. This brings an element of particularity to the process of collective memory, which is appropriate for the remembrance of a collective of individuals by a collective of individuals. NARELLE YABUKA IS A PERTH-BASED FREELANCE ARCHITECTURAL/DESIGN WRITER AND EDITOR.MANDURAH WAR MEMORIALArchitect Hames Sharley—project team William Hames, Jessika Hames, Brook McGowan, Mason Harrison. Structural and electrical engineer Kellogg Brown & Root. Client City of Mandurah.

Builders Pindan, City of Mandurah.