Photography by John Gollings

Review

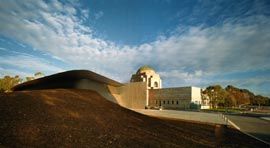

The rolling ground plane and complex curving forms of Anzac Hall, with the Australian War Memorial seen beyond.

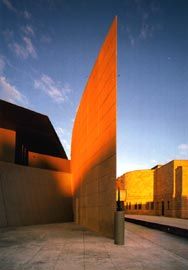

The tapering concrete blade wall.

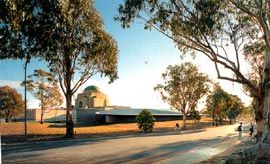

Sitting below the War Memorial parapet, Anzac Hall is invisible from the land axis of Anzac Parade.

The blade wall, designed to provide a nuetral backdrop to the memorial, and glazed bridge link.

Looking from the mezzanine, over the exhibition hall.

Given the symbolic potency of the Anzac legend, the Australian War Memorial has long held a central place in mainstream Australian national identity. And regardless of the problems inherent in so called “Digger nationalism”, and that mysterious transmutation through which bloodshed and military defeat at Gallipoli came to be seen as the birth of the nation, it would be a hard heart indeed that was unmoved by the memorial’s formal commemorative spaces. The cloistered Honour Roll, with poppies pressed between the bronze name plates, remains a profoundly sorrowful memorial to wasted life. The domed Hall of Memory containing the tomb of the unknown soldier, the outdoor pool of reflection, and the eternal flame are similarly sombre, funereal, and quasi-religious in character.

Nevertheless it has always seemed rather anomalous that the Australian War Memorial is called by that name. Since its opening in 1941 it has also functioned as a specialist war museum, displaying the artefacts and presenting the history of Australia’s involvement in international warfare. Balancing the roles of museum and memorial produces certain tensions. A museum has a responsibility to present the evidence of historical events in as accurate, objective, and comprehensive a fashion as possible, whereas a memorial works at the level of affect, provoking empathy and insight through emotional identification. With the completion of Denton Corker Marshall’s Anzac Hall extension to the War Memorial in June 2001, the relationship between museum and memorial has taken another form again.

At first glance, Anzac Hall appears to contrast with the existing war memorial building in almost every respect. In its massing, materials and detailing, the extension could hardly be further from the blocky monumentality of the original. The only explicit link between the old and new buildings is a light glass and steel bridge at first floor level, and it is thus possible to circumnavigate both the old and new buildings at ground level. Upon closer examination, though, Anzac Hall also establishes a subtle geometrical reference to the original building. This is most evident in the shape of the plan: a curved trapezoid in which the angle of the outer walls radiates outward from the centrepoint of the memorial’s dome. This radial pattern is also revealed inside the hall in the orientation of the main I-beam support columns, and dictates the fan-like arrangement of the roof structure. As such, the Anzac Hall addition relates to the original building at the most literal level.

From the outside, Anzac Hall is an enigmatic object: there is no direct public access from the exterior, and its mass is largely concealed beneath ground level. In part, this low profile was a response to principles laid down by the National Capital Authority, which not only dictated the position of the extension – behind the existing war memorial – but also demanded that it remain invisible from the land axis of Anzac Parade, which visually links the war memorial with Parliament House. The most dominant architectural elements of Anzac Hall are thus a long blank concrete wall, tapering to a dramatic blade at each end and intended to act as a neutral backdrop to the memorial, and a wide expanse of complex curving roof. Little of its perimeter wall is visible – it is sunken into a rolling ground-plane planted with native grasses, the gentle curve of these earthworks echoed in a roof form which rises in a slow swell towards the centre. For all these curves, though, in plan and in elevation, there is nothing organic about Anzac Hall. Its dark metal roof and panelled walls mark it out from the surrounding light eucalyptus bushland, and from the dun-grey stone and copper of the war memorial, as something alien. Half submerged, crouched behind the existing war memorial and camouflaged within the terrain, it has an aspect of stealthiness.

Anzac Hall’s palette of materials is sympathetic to its cargo of military metalwork –especially in its allusions to aircraft detailing. The roof plane tapers at the edge into a distinctly wing-like, continuously curved rim. This enables the roof to be read simultaneously as heavy and light – an enormous uninterrupted plane settled upon a pedestal, but one which may swoop into flight again at any moment. Internally, the wall cladding of the service “core” is shiny riveted aluminium, reminiscent of a World War II bomber.

The hall is entered via the newly refurbished Bradbury Aircraft Hall; the visitor passes along a narrow axial bridge and enters the hall centrally, on a mezzanine level.

The mezzanine accommodates services within its back wall, a cafe on the eastern side, and an exhibition space on the west. From this level the vast space of the hall is immediately laid out, and the visitor is able to survey the “large technology objects” arranged below. Suspended opposite the point of entry is the stern of one of the memorial’s major drawcards – the Japanese midget submarine, which is dramatically installed across the length of the space. The large scale multimedia presentations which periodically occur around this submarine, recreating its entry into Sydney Harbour in 1942, can be observed directly from the mezzanine level, from a stand-alone viewing platform accessible down a short ramp, or from bench seating at ground level.

The interior of Anzac Hall is immediately striking, not only for the sheer volume and span of its vaulted space, but also its gloominess – it is remarkably dark, and in this it is reminiscent of a classic “black box” theatre design. This impression is reinforced by the “panoramic” curve of the back wall, which, even though it is painted a uniform dark grey, suggests a cyclorama or stage backdrop. Tanks, trucks and planes are arrayed within this cavernous, hangar-like interior, each picked out of the gloom in its own dramatic pool of light. But given that the objects exhibited are not prototypes or models but actual war remnants, it is eerie to see them neatly lined up, silenced and neutralised.

In fact, at times there seems a vaguely discomforting lack of gravitas. Given the quasireligious rhetoric of much of the memorial – its objects are referred to as “relics” rather than artefacts, for instance – the breezy references to “big things – hourly shows” at the entry to Anzac Hall are jarring. In stark contrast with the tone of the memorial’s commemorative area, the installation of Anzac Hall strikes one as being uncomfortably like a bizarrely martial “motor show”.

Perhaps this is more fairly a comment on the exhibition design, or indeed the brief itself, rather than the architecture. But the very neutrality of the building tends to imply a certain mode of display, and bears again on the War Memorial’s overall balance between the role of memorial and museum. In the original building, the shift between these registers is reflected spatially, in the transition between formal commemorative spaces and exhibition galleries. The passage between these is marked by a shift in tone, whereby deep melancholy is gradually displaced by a kind of detached, mildly blokey curiosity. Perhaps Anzac Hall forms the culmination of that trajectory, the point where the memorial function definitively ends. Even given the fact that the addition is projected from the dome of the original Hall of Memory, this sophisticated geometrical connection is too abstract to draw a tangible link with the memorial’s central role, as a national monument. There was an opportunity for Anzac Hall to make a comment upon, or even a reconciliation between, the role of memorial and museum. Regardless of the building’s fine qualities, however, it does not do this. The architecture has an understated industrial elegance, but, crouching in the shadow of the War Memorial, it effectively ducks the question of commemoration.

Naomi Stead is an associate lecturer in architectural theory, philosophy and cultural studies at the University of Technology, Sydney

Project credits

ANZAC Hall, Australian War Memorial

Architect Denton Corker Marshall. Acoustic Consultants Eric Taylor Acoustics. Structural, Traffic and Civil Engineers Taylor Thomson Whitting.

Services Engineers Norman Disney Young.

Hydraulics and Fire Protection Consultants Hughes Trueman Reinhold. Building Surveyors Fire Safety Science. Cost Planners/Quantity Surveyors Donald Cant Watts Corke (ACT). Project Manager Root Projects Australia. Contractor John Hindmarsh ACT.

Client Australian War Memorial.