I first encountered this project in 2005 when, as part of the urban design team at the City of Melbourne, I had the opportunity to review and comment on the development application. Support was forthcoming, but the realization of the project has surpassed the challenge of interpreting the application package in an accurate and critical way. What has been created is the result of a productive and positive collaboration between client and architect, with practical completion at the end of 2007.

Looking down Ridgway Place. The geometric, permeable forms of Monaco House contrast with the high wall of the Melbourne Club opposite.

Image: Trevor Mein

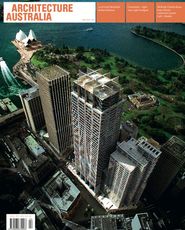

With Monaco House, a little gem that resides in Ridgway Place, McBride Charles Ryan has again delivered a building consistent with its design agenda and folio. Ridgway Place is one of the myriad laneways for which Melbourne is renowned. Located between Collins and Bourke Streets, at the eastern end of the central business district, it is used frequently as a pedestrian shortcut, with little car traffic. Ridgway Place is five metres wide, bordered on the west side by a long brick wall that houses the Melbourne Club. On the east is the 1950s formalism of the Lyceum Club and two other buildings of similar size. Looking up, we see Nauru House, the ANZ Towers and Telstra headquarters. Thanks to the greenery of the Melbourne Club and planting on Little Collins Street, the precinct easily fits its “Paris end” tag.

The title “Monaco House” evokes the cinematic imagery of James Bond, Grace Kelly, racing cars and streamlined super-yachts. The project selectively represents these associations, yet remains true to the fact that it is very much Melbourne. The client, the Honorary Consul to Monaco, has procured the first building to be granted naming rights outside Monaco. This adds to the mystique of what happens inside when peering in from the public domain.

In and around Ridgway Place are bars, restaurants, clubs and hotels characteristic of a city that has grown up. Some of these survive on the old school tie, others survive on new media. Ridgway Place is smack bang in the big end of town but, in contrast to the many generic offices, Monaco House offers its occupants an environmentally conscious building both internally and externally.

Located on a site of just 101 square metres, the building is four storeys high. Such dimensions demand innovation. The spread of program includes a cafe, consular activity, offices, meeting areas and a rooftop garden. It is worth noting that the physical footprint of this building is dwarfed by many apartment buildings currently on the market in Melbourne’s Docklands, at the edge of the CBD grid or on St Kilda Road. Perhaps not coincidentally, Monaco itself is built at these miniaturized dimensions.

Entry to the second-level balcony.

Image: Trevor Mein

Monaco House is part of a suite of small individual buildings consistently used to highlight and promote the marketing image of the central Melbourne city to the world. Melbourne laneways and arcades are internationally recognized and rightly celebrated. They give Melbourne a porosity that encourages hidden treasures, active and unexpected frontage and vitality. The effects of “edge” are all too apparent in the compound walling around the clubs opposite Monaco House. In this context, the variety and porosity of McBride Charles Ryan’s design is particularly notable – its passive ventilation, its multi-use interior spaces and a permeable facade that allows glimpses to the edge of the CBD and the serene, mature landscape of the Melbourne Club trees.

The building sits comfortably in its surrounds, a cheerful newcomer among the Melbourne clubs that gives a dose of glee to the streetscape and suggests a preference for a city of variation. But the neighbourhood character of Monaco House operates beyond the simple comparison to immediate built context that is commonly found in the Victorian statutory planning system – its community is more like the phenomenon of Facebook. That is, the neighbourhood character of Monaco House is more akin to Alkira House, Storey Hall (ARM), the Art Nouveau buildings scattered along Collins, or the Capitol Theatre (Burley Griffin) and the many “friends” it would have internationally. What separates this building from these “friends” is its surprising physicality despite its size. It is testament to a successful testing via modelling software.

Looking from the cave-like balcony on the third level. The leafy view is of the mature landscape of the Melbourne Club.

Image: Trevor Mein

All good buildings prompt us to think about their host metropolises. This one provokes a worthy rethinking of the layered histories that make up this city. Early subdivision plans of Melbourne show the uniqueness of the city grid. But, like most modern cities, as Melbourne developed over time the format of the allotments became increasingly prescriptive, and allotments changed character as smaller blocks became consolidated. The modern tower, shopping centre and other flat-pack office buildings rely on this progression. Monaco House, however, honours an allotment that strongly suggests another era in Melbourne’s history. It is a project of boutique celebration.

In Crash, J. G. Ballard describes a subculture in thrall to the geometry of chaos, where forms break down and become something other. When I visited this building, people would slow as they encountered it. Although this is not the same as chaos, the building commands a similar visual effect and fascination. The subtractive corner detail spreads vertically and appropriates the top floor elevation. As a crumpled image in motion it could prompt the question: What stage of morph(ological) change is this building in?

Such ambiguity demarcates this building from other max-lot developments – not just in the facade but in an active attempt to bypass the cuffs of allotment. It does this through the use of windows, balconies, rooftop access, interior/exterior collaboration, visual permeability and environmentally responsive design elements, as well as savvy land use.

Entry to the building is through an azure backlit lobby. The view out through the interior on the upper floors is as if from a cave cut into an imagined limestone cliff. There is a duality to the internal planning of Monaco House – it fights to be an office and it fights to have liberty from this assigned restriction.

The warped green surface of the rooftop deck.

Image: Trevor Mein

Monaco House is part Moderne and part Raygun Gothic. This is evident in the approach taken by client and architect to create such a new building, but also in the themes that order the project. Lamination is one such idea. Surfaces become reveals, walls become upholstered ceilings, whiteboards slide behind joinery, the entry foyer becomes a backlit portal and the rooftop a green-wrapped and warped surface. Most important is the way that one use slides into another. As a microcosm of city it successfully represents socially sustainable ideals.

The corner condition could be a constraint, but rather than accept this as a restrictive architectural element, the client and architect have developed it into a larger idea. I am uneasy comparing architecture to sculpture, but it remains unclear whether the face and edges of this building are something cut out of a prefigured object or the inverse. This condition of ambiguity is something that we should celebrate as a positive for a city.

In opposition to the dark and dank buildings that normally fill small laneway allotments, this building is bright, thermally confident and multi-directional. It participates in the city as laneway art as well as a building, and through this provides real and tactile lessons for other developments in the city.

Credits

- Project

- Monaco House by McBride Charles Ryan

- Project architect

- Robert McBride, McBride Charles Ryan

- Architect

- McBride Charles Ryan

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Debbie-Lyn Ryan, Drew Williamson, Adam Pustola, Fang Cheah

- Consultants

-

Builder

Easton Builders

Building surveyor PLP Building Surveyors & Consultants

ESD Cundall Australia

Fire safety engineer Lake Young & Associates

Quantity surveyor Construction Planning and Economics

Structural engineer VDM Consulting

- Site Details

-

Location

Ridgway Place,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

- Client

-

Client name

Honorary Consul of Monaco

Source

Project

Published online: 1 Mar 2008

Words:

Simon Drysdale

Images:

Trevor Mein

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2008