University campuses have been identified as potentially important nodes for encouraging increased urban densities in Australian suburbs. Suburban university campuses are indeed full of activity and people, and it seems logical enough to think that with appropriate planning policies, infrastructural investment and urban design, this activity could leaven development around the node. At its heart, this would be development of housing and retail to support campus users, and of research-based businesses and institutions that can spin out of university enterprises. But development begets development, intensity of activity more intensity still. The hope is that – if the right levers were pulled in relation to transport infrastructure and encouragement of denser housing patterns – universities would be catalysts for consolidation in the suburbs.

In Melbourne, there are a number of major suburban university campuses, the two most notable being La Trobe University’s campus in Bundoora and Monash University’s Clayton campus. They were both established in the 1960s, on what were then respectively the northern and eastern edges of the metropolitan area. Both campuses are knitted into networks of other institutions, employment clusters and various economic and commercial activities. But none of this is experienced as particularly urban or intensive; none of it produces densities of activity or inhabitation that mitigate the amount of travel undertaken by those who study or work at the universities.

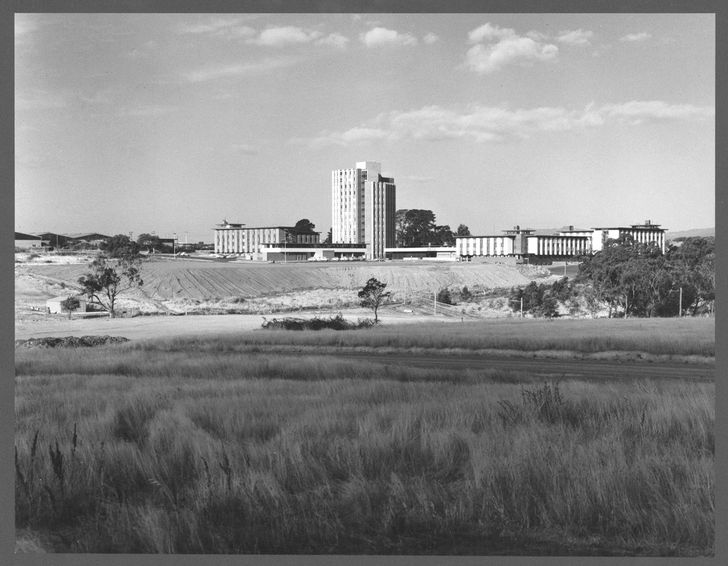

The Monash University Clayton Campus circa 1967.

Image: Wolfgang Sievers, Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria

The universities themselves have attempted to address these issues. Monash’s recent campus planning – undertaken by MGS Architects – has focused on improving the urban qualities within the Clayton campus and on introducing more student housing. The 1960s palette of brusquely monumental academic and administrative office slabs mixed with more characterful buildings for lecture theatres, libraries and so on had little of particular architectural distinction. However, the extensive landscaping that took place during the establishment of the Clayton campus has resulted fifty-five years later in impressive stands of mature planting. While this is an important environmental attribute of the place, much of it rings the central campus in a way that emphasizes separation from its surroundings. In turn, the qualities of the urban context exacerbate this separation. The Monash Clayton campus is cut off to the east and south by major, multi-lane arterial roads. To the north, the now impenetrable thicket of CSIRO research facilities is a major barrier that presents a high fence topped by barbed wire to its bleak adjacent neighbourhood, while to the west, the campus drifts into suburban nowheresville with no discernible edge at all. Reliance on private vehicles for students and staff travelling to Monash has added to the psychological separation of the place, with vast carparks at the campus’s main northern and southern entry points.

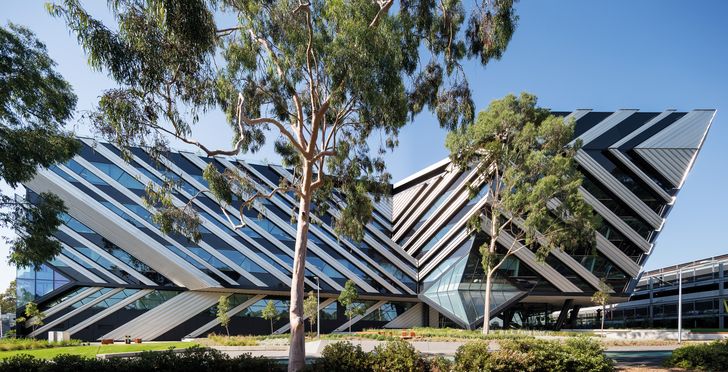

Much has been done to make things better. The introduction of a high- frequency bus service between Clayton and Huntingdale Railway Station has encouraged the use of public transport to get to the campus. MGS’s campus plan has fostered a pattern of pedestrian streets and the reconfiguring of large landscape spaces at a more intimate scale, with plazas, seating and coffee places. This has made it easier to navigate the campus once the barriers around have been negotiated. Two new buildings by Lyons Architecture (the mysteriously named Green Chemical Futures and New Horizons buildings) offer the visual zing of Lyons’s other educational buildings. It’s all much physically richer than once it was.

The New Horizons building by Lyons Architecture.

Image: John Gollings

These incremental improvements, however, have not been game changers. The high-frequency buses have not made up for the failure by the state to provide the direct rail connection that was envisaged in the 1960s. The campus “streets” have no connection to the unreachable street pattern beyond. The new buildings offer better student amenity and address new configurations of inter-institutional collaborations and industry partnerships but beyond this have only ameliorated their immediate campus precincts. A new Learning and Teaching building designed by John Wardle Architects and currently being constructed at the Clayton campus’s main entry point perhaps may do somewhat more. While encouraging students to stay on site, it will also start a built edge to the campus that if extended might transform Wellington Road’s streetscape. At the very least, it will give a visual signal of the university to the endless cars passing by that is more than a big blue Monash sign.

But we have our doubts about how much deep urban change it can achieve. The attributes of the Monash campus that inhibit integration with surrounding neighbourhoods will be very difficult to overcome. This is not merely because of the physical barriers to connection – Monash’s carparks, berms and swathes of landscaping, the scale and traffic volumes of Blackburn and Wellington Roads. It is also because the neighbourhoods themselves have characteristics that actively work against connection. While many of the businesses and institutions to Monash’s east have evolved out of university activities, they are embedded in patterns of development and connection that are about metropolitan rather than local scale, readily available car parking and access to the Monash Freeway being attractors as much as the university’s proximity. To the south, the neighbourhood is residential rather than commercial, but again, better connection for this area to the Monash campus will achieve little without some broader transformation.

An external visualization of the building showing its northern elevation. Renders: courtesy of John Wardle Architects.

Image: Courtesy John Wardle Architects

And here’s the rub. As it is, metropolitan planning in Melbourne does not have the sophistication to deal with these issues. Thinking of how universities could be hubs of urban development requires a degree of integration and interaction between different kinds of inquiry inconceivable in our current planning regime. The politicization of infrastructural planning and university funding in Australia further complicates this. To think of the future role of universities in urban development should, as a matter of course, involve considering the future of universities, the futures of their major activities of teaching and learning and research, how international or local they will be, how much campus-based and how much virtual. It is admirably optimistic for Monash to build a huge Learning and Teaching building designed by fine architects, but what is the future of teaching and learning and of how universities interact with their students? Will students retain a physical presence, especially on outer-urban campuses with troublesome access? In our view, how this particular attribute of universities will develop is unclear but it will have a significant impact on how campuses can lead urban intensification.

As it is, the structure of the academic year means that students are on site for only about half the calendar year and only a small minority stay on in the evenings, for private or group study. Sure, there are economic pressures to use facilities better, with changes in the academic year and the length of the teaching day. Much is also made of the value of face-to-face encounters in teaching and research, as in business and entrepreneurship. But those of us involved in teaching at tertiary level can see that large-scale didactic teaching is dying, even as the scale of classes is growing. Students are increasingly taught to teach themselves and to gather, analyse and assimilate information independently. University- based interaction is increasingly restricted to course projects, while social interaction is largely off-campus and no longer principally among classmates. Much of that is virtual rather than corporeal – a development that the campus designers were unable to predict but to which the university nonetheless has had to respond.

Perhaps the manifestation of the campus as a pleasant oasis in the uninspiring circumjacent suburbia will become its principal attraction. Much in the way Monash’s original designers believed the planting of native trees and plants would attract indigenous fauna to the site, a safe and stimulating environment might draw in students, at least during semester time. On the occasion of Monash’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1986, the historian John Rickard commented that the university’s early intentions to connect with its adjacent suburban communities had not been realized: “Clayton and Oakleigh were never destined to play ‘town’ to the Monash ‘gown.’” Nothing has really changed; perhaps they simply can’t.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 24 Aug 2016

Words:

Paul Walker,

Andrys Onsman

Images:

Courtesy John Wardle Architects,

John Gollings,

Peter Bennetts,

Rhiannon Slatter,

Wolfgang Sievers, Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2016