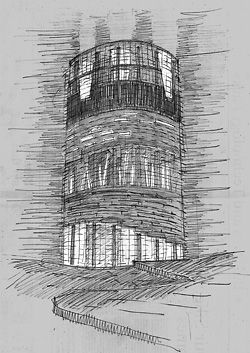

Sketch by Estelle Grange-Dubelle.

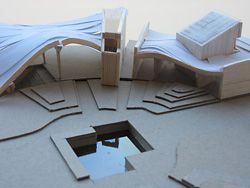

Scale model by Lily Tandeani.

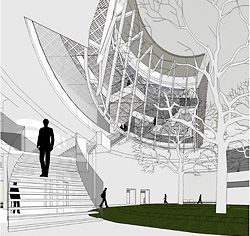

Courtyard image by Lionel Teh.

Temporary gallery internal perspective by Boris To.

Is architecture under-recognized by the Australian public? How might we change this? Philip Drew argues the need for a museum of architecture.

The awareness of architecture in the community is improving and design is being given greater importance than it has previously, but Australia still lags behind other nations in terms of a public embrace of the discipline. Architecture was unrepresented at the Australia 2020 Summit held in Canberra earlier this year, which illustrates the wider problem. Australia needs a year-round national focal point for architecture – a place of scholarship, research, central archives, lectures and world-class exhibitions, both temporary and permanent. It could serve as a beacon for architecture, whose light would be seen by the wider public. It could change the public’s perception of the importance of architecture.

The institution that could best do this is a museum of architecture – one that is not limited to state interests but is truly national in its focus, activities and collections. There are some sixty-five architecture museums in the world according to the International Union of Architects website, some going back as far as 1956. Sir John Soane’s Museum in London dates back to 1833. In Australia, we have yet to make a start!

In his novel Tunc, Lawrence Durrell made the point that our very first shelter is the womb. Architecture is a more permanent version of clothing. The tent is somewhere in between – you might say a looser and larger variation of clothing. In a particularly telling observation, Durrell wrote: “[Architecture] is the hero of every epoch. Into it can be read the destiny, doctrines and predispositions of a time, a being, a place, a material.” He went on to say that we live in an age of fragments – note that this was said in 1968 – where all we can do is “flounder, improvise and hesitate”.

Thus the establishment of such a national institution represents much more than fulfilling a narrow professional interest; it concerns giving coherence and meaning to our culture, showcasing our finest designs, exhibiting to the world our uniqueness, illustrating lessons in sustainability and honouring the Aboriginal architecture that existed prior to European settlement. The creation of a national archive of drawings, models, images, documents, letters and media comment will prove invaluable to future generations.

In summary, the museum should aim to:

- Act as a national lighthouse for architecture and design.

- Stimulate the public’s understanding and appreciation of architecture.

- Present displays on “classical” Australian Aboriginal architecture, individual architects and architectural topics or themes.

- Collect and preserve drawings, records, models, images, videos and contemporary comment, direct from the drawing board.

- Commission research, surveys and retrospectives on leading architects and on Australian architectural history.

- Host public forums on architectural matters of public concern and lecture series by eminent scholars on architectural subjects of Australian interest. These should be of a similar quality to the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard University.

Does anyone doubt the economic importance of architecture, in addition to its contribution to our wellbeing and health and the pleasure we derive daily from living in beautiful, fulfilling surroundings? It increases our productivity and our sense of who we are. The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports that annual expenditure on residential and non-residential building in Australia was close to $66 billion for the year 2007–2008. The lack of a museum of architecture in Australia is nothing short of a scandal.

So how should those interested in seeing such a museum established in Australia act to promote it? First, we must tell the Rudd Government that architecture cannot be ignored, that it is economically critical and that it represents Australia to the world better than any television tourist campaign does. How many overseas people know and remember Australia because of the image of the Sydney Opera House? Architecture makes a priceless contribution to situating Australia globally.

We need to get our university schools of architecture behind the project, along with the Australian Institute of Architects (which at present appears to consider that it is a waste of time) and allied institutions such as the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand. But most importantly, a national museum of architecture needs to be spoken about in the Australian community at large and publicized, so that politicians will be persuaded that it is in their political self-interest to give it their support. Potential private sponsors also need to be identified. This will all take time and consistent pressure. But with a federal government that has yet to discover “architecture”, the time could not be more fertile or propitious – it is an empty prospect that we advance into.

Architecture, it has been said, is about imagining the future. It is high time that architects began imagining an Australia in which architecture is considered important. The existence and activities of a museum devoted to architecture would go a long way towards spotlighting architecture nationally.

The third-year design studio run at the University of New South Wales earlier this year tackled the problem of designing a new Australian museum of architecture on the Observatory Hill site in Sydney (controlled by the Powerhouse Museum). Many of the designs exceeded expectation. One even developed the concept of the veranda, expanding on the idea of a transitional linking space between outside and inside.

Such a museum should not only lead the world in setting new standards of accessibility and imaginative exhibition techniques, it should look Australian, or at the very least pose the question, “What does it mean to build in Australia?” What has this continent given our culture that is special and distinct from the outside world? What makes us different?

Walter Burley Griffin wisely noted in 1932 at the height of the Great Depression that you cannot tune into or switch off architecture like the radio (and the theatre, literature, painting or sculpture might also be added). Architecture is unavoidable when you step outside. Given its wide and pervasive impact, should it not receive the recognition it warrants?

Philip Drew is a Sydney-based author and writer.