Review Catherine De Lorenzo

Photography Brett Boardman

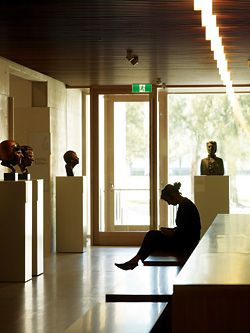

The Gordon Darling Hall foyer, which replicates the proportions of King’s Hall in Old Parliament House.

The official arrival court to the National Portrait Gallery of Australia.

The building has been designed as a series of bands linked by narrower circulation passages, as is clearly expressed externally.

The north-eastern elevation.

Detail of the ceiling structure of the Gordon Darling Hall foyer.

Looking down one of the narrower, darker passages between galleries.

The view from one gallery to another across a passage.

Slots in the gallery walls allow visitors to see through to new spaces or return to old.

The scooping of natural light into the gallery spaces and human scale are integral to the display of the portraits.

Looking from the foyer entry out to the western court.

Glazed walls at either end of the passageways allow glimpses into the landscape.

Let your song be delicate

The skies declare

John Shaw Neilson, Song Be Delicate(1913)

The National Portrait Gallery, by Richard Johnson and Graeme Dix of JPW, reveals a new architectural maturity in Canberra and, perhaps, the nation. Eschewing both the symbolic high jinks of Ashton Raggatt McDougall’s National Museum of Australia (2001) and the complexities and monumentalities of Colin Madigan’s High Court of Australia (1980) and National Gallery of Australia (1982), its near neighbours, the NPG has a thoughtful, assured presence.

This deceptively simple building works from the inside out. Central to the brief and the architectural program was the idea that the building show the often life-sized portraits to advantage. This is done by the use of “appropriate scale, [taken] from the human body, the measure of portraits” and “integration of the natural beauty of Canberra, its distinctive light and landscape setting”.1 Human scale and the scooping of natural light into the gallery spaces are the generative design principles for the display of portraits in various media, including miniatures, paintings, sculptures, photographs, cartoons, prints, ceramics and digital media. Skylights running the length of the walls bounce light onto angled panels down into the viewing spaces. Daylight entering these windows is tempered by both screens and blackouts so as to regulate appropriate lux levels in the galleries. The aim is for the viewer to see the art under optimum viewing conditions while being subliminally aware of passing clouds or the tracking of the sun across the northern sky. Through a series of white painted trusses, light washes down the walls to energize the spaces and allow the surfaces and the colours of the artworks to hold our attention as much as any curiosity we may have about the sitter. Even the most conventional portraits come to life under these conditions. Most spaces read as neutral or white, although on closer observation the wall panels holding the works are tinged with green, pink, mauve or cream, to suit the particular hang. These panels also serve to break the 4.3-metre height of the walls, so that portraits are seen to advantage.

Until three years ago the site, within the north-east apex of the Parliamentary Triangle, constituted part of the lawns that sweep down from Old Parliament House to the edge of Lake Burley Griffin. But for a sprinkling of trees, especially around the borders, the plot might have seemed lacking in natural features or archaeological importance. History, however, suffuses every aspect of the site and, I would argue, the design of the building, but it is a history devoid of pomp or jingoism. The first layer of history concerns an Aboriginal regard of the land as indivisible from those who belong to it. This idea is used in one of the inaugural temporary exhibitions, Open Air: Portraits in the landscape, where what appear to be Indigenous images of the land are at times exhibited as portraits of the people. A similar sensibility is absolutely integral to the NPG design. From the moment of entry – looking through the beautifully crafted wood and glass doors, past the foyer to the landscape stretching to the Questacon building and the National Library of Australia – one senses that the building is embedded in the land and that we are too. The ability to see through the building to the landscape beyond is not just an exercise in transparency and openness (which it also is), but an architectural response to a profound sense of engagement with the land and its distinctive light, because the museum houses a collection about people.

The second layer of history is the Griffin plan, which indicated five terraces of buildings in the triangle emanating from Capital Hill. JPW played with the idea to produce a relatively small building of five 70-by-12-metre bands, linked by narrower (3.6-metre-wide) circulation passages. The idea of the five bands proved a clever one. Some visitors will approach the entrance, which is in the fourth band from King Edward Terrace, by walking past the first three bands; others might cross the footbridge from the National Gallery and note the main entry, but choose to enter the building via the indoor/outdoor cafe at the north-east corner of the fifth band. Most visitors, however, will probably emerge from the underground carpark into the generously proportioned forecourt, before entering the Gordon Darling Hall foyer. The amplitude of the eight-metre-high foyer, which expands at floor level to include the passages, replicates the admired proportions of King’s Hall in Old Parliament House, while its bolted and sometimes lined trusses echo the direct approach to materials found in a woolshed.

Once in the building, most people will begin their visit by entering the third band, central to which is the Marilyn Darling Introductory Gallery, dedicated to portraits of our own time. This band also has two temporary exhibition galleries, toilets and a one-hundred-seat theatre. From the Introductory Gallery they pass through the first of two relatively dark passages, with seating and a scattering of portrait busts on pedestals. Glazed walls at either end frame opportunities to observe the landscape to the west or perambulating visitors to the east. These first and second bands display the permanent collection in a series of six or seven spaces. Two small glazed viewing boxes protrude from the wall facing King Edward Terrace, providing the visitor with a brief respite from the intensity of looking and at the same time enabling her to be seen by passers-by, as if she were a live exhibit. The only two-storey wing is the fifth, administration, band along the northern boundary of the building, where a bookshop, cafe and meeting rooms on the ground floor are surmounted by offices and related facilities above. Slits in the walls allow for glances through these various bands, allowing visitors to anticipate new spaces and return to old. The entire building sits on a basement for parking, storage and security. Even the slightly higher roofing for the fourth and fifth bands sits 9.3 metres from the ground, well within the allowable height limits for the site. This enables the canopy of the existing trees to effectively hide the building. It is a flexible design, with plant embedded underground so as to facilitate spatial change on the ground floor, generous above-ceiling cavities for easy electrical refits, and enough space on the site for a fifty percent expansion to the western perimeter.

The democratic imperatives behind the Griffin plan for the national capital are also reflected in the building program: staff and the gallery’s Circle of Friends share the same dining facilities as visitors, as do busloads of tourists and schoolchildren with regular visitors entering the building. Whereas the Griffins combined their democratic purpose with a thorough understanding of architectural archetypes, in the NPG’s design the democratic ethos is expressed through proportion.2 Recognizing that the brief’s requirement that an appropriate scale be “taken from the human body, the measure of portraits” was indebted to Vitruvius’s (III, 1,1) dictum that a temple “must have an exact proportion worked out after the fashion of the members of a finely-shaped human body”, the architects seized the opportunity to play with golden section ratios. Indeed, this proportional system informs all aspects of the design. Even where minor compromises have been made, the proportions of spaces and details remain harmonious and make visitors, and by extension the people represented, feel at home.

Vestiges of the Griffins’ democratic plan are embedded in a third layer of history, the National Capital Authority’s 1988 National Capital Plan for the Parliamentary Zone. This “place of the people” must, according to the Plan, balance politics and culture, welcome people, celebrate Australia’s history and society, represent Australian excellence (especially design excellence, materials and craftsmanship), emphasize the importance of the public realm, make access easy and open, reinforce the integrity of the visual structure and strengthen the relationship between buildings and landscape.3 Of the five campuses within the zone, the NPG now joins the High Court and the National Gallery as defining the “Arts and Civic Campus”. Although ultimately a pavilion in a park, the NPG brings a new density and energy to the campus in several ways. Materially, it acknowledges the concrete and glass of its neighbours but masterfully incorporates wood into the fenestration, ceiling trusses and various fixtures along the walls, with the result that the building feels finely crafted. An understanding of how the 45 degree angles of the High Court intersect with its own 90 and 180 degree geometries informs the shared landscape design. Socially, the indoor/outdoor cafe at the north-east corner of the building, closest to the footbridge linking the NPG to its neighbours, provides a lively hub sorely needed in this part of Canberra.

Less obviously but significantly, the building reflects a fourth and most recent layer of history, a readiness of white and black Australians to consider their shared histories and to understand their links to the land. Between the unofficial Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the lawns of Georges Terrace and the very official and “designed” Reconciliation Place – a Howard government project launched in July 2002 and brought to completion by the NPG – the NPG sits easily within its context. With no need to adopt patronizing or appropriated symbols, the building, cleansed and accepted by two Indigenous smoking ceremonies marking the commencement of construction and the staff occupation of the building, simply stands its ground, confidently deferring to the land as the measure of the human and the cultural.

This accomplished design, realized despite a less than satisfactory finance and construction model, owes as much to the thoughtful brief as it does to the experience of architects used to working with art and artists.

Catherine De Lorenzo is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of New South Wales.

1. Quotes taken from the brief, National Portrait Gallery: Principal Design Consultant Registration of Interest [2004].

2. Jeff Turnbull, “The Architecture of Walter Burley Griffin: archetypal patterns” in Fabrications, vol. 15 (1) (July 2005), pp. 1–26.

3. National Capital Authority, National Capital Plan, Amendment 33 (September 2001), pp. 4–8, http://downloads.nationalcapital.gov.au/plan/NCP/amendments/Amdt_33.pdf, accessed 10 January 2009.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, CANBERRA

Architect

Johnson Pilton Walker—design directors Richard Johnson and Graeme Dix project associate Adrian Yap project team Mark Berlangieri, Naigel Carusi, Andrew Christie, Andrew Clemenza, Andrew Daly, Monique Clark, Wayne Dickerson, Jorg Hartig, Meiling Honson, Mathew Howard, Dickson Leung, Timothy Osborne, Georg Petzold, Adrian Pilton, Duncan Reed, Roger To, Carlie Waterman.

Acoustic, structural, civil, fire, geotechnical, traffic and facade consultant

Arup.

Electrical, lighting, mechanical, security and communications consultant

Steensen Varming.

Hydraulic and fire services consultant

Warren Smith and Partners.

Vertical transport consultant

Norman Disney and Young.

Building surveyor

Advance Building Approvals.

Landscape architect

Johnson Pilton Walker.

Access consultant

Morris Goding.

Food and beverage consultant

Sangster Design Group.

Builder

John Holland Group.

Client

National Portrait Gallery.