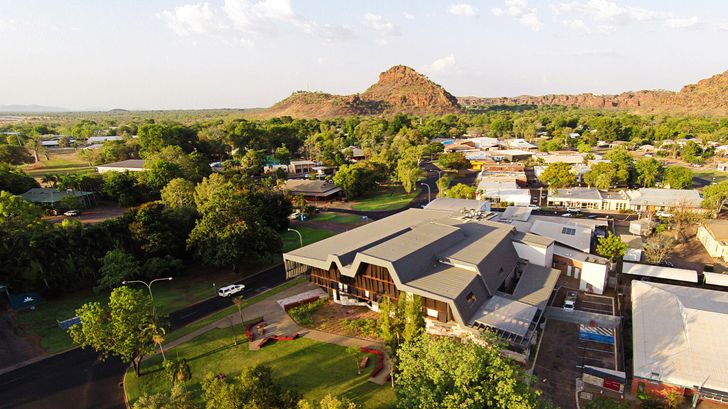

We are in Miriwoong ancestral lands, which sweep from the Ord River and Hidden Valley to Dingo Creek and the canyons of the Keep River in the Northern Territory. Rugged and red, it is the midst of the “Wet.” Boab trees are swollen – it is hot, very hot. In Hidden Valley, we are embraced by a diorama of crusty, red ochre striated sedimentary stone shaped over aeons by wind, rain and seepage. This is the red, the red of Australia that starts in the Top End and goes to the edges of the south. No driving, so we walk through gorges and slots – at last, there is a breeze. From this crusty ochre embrace we drive into the green, irrigated flat lands and Kununurra. The (new) town is folded around the crags of Hidden Valley and Lily Creek Lagoon. In a green grass swathe under shade trees on the side of Messmate Way, Aboriginal families coalesce in the cool black shade. We are at the Courthouse: from Messmate Way it is craggy in plan and section, implying its inner workings with fine rusty steel louvre screens and a honed stone base in red and ochre with sliding blue courses. In contrast, around the corner on Coolibah Drive, there are straight lines and planar perforated shading. The architecture looks so much better, subtler than the photographs!

We all know the disaster of the deaths of Aboriginal people in custody, brought to public consciousness by the 1987 Royal Commission. There has been little progress in closing the huge “gaps” nationally, particularly in the Indigenous Top End. Australia’s Indigenous people have deep kinship relations and specific and mystical connections to the land – a social form that is, in a sense, the opposite of modern acquisitiveness and individualism. Add to this vast distances and alcohol and we have a challenging social situation. The New Kununurra Courthouse by TAG Architects and Iredale Pedersen Hook Architects – along with the West Kimberley Regional Prison by the same architects – is at the forefront of trying to respond to the region’s social complexities. It recognizes the different needs of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and, above all, manifests a special humanity. As architects it’s important that we organize a building with a sense of the ancestral land and with a universal humanity.

The form of the courthouse’s folded roof mimics the form of Kelly’s Knob.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The courts are the centrepiece. “Court” comes from the Old French word “cort,” derived ultimately from the Latin word “cortem,” meaning enclosed yard, and “hortus,” meaning garden. In a court, we put forward our cases and articulate our disputes, not secretly, but in the open in front of our peers and the public. It is easy for “respect” and “gravitas” to become all-consuming: giant coats of arms, wigs, gowns and raised podia for judges. But in the Kununurra courtrooms, the strong placemaking of the entrance, waiting and meeting rooms becomes quieter, fairer: plantation eucalypt veneer with grey carpet. The doors have glazed panels. Importantly, in the Magistrates Court there is a window. This is an open space. In this court, all the furniture is on wheels to permit a reordering for mediation or for a less confronting format for a Children’s Court.

In the Jury Court upstairs, a gowned judge explains the nuances of sentencing to an offender on a television screen. “Do you understand?” she asks. There is a grunt and he disappears from the four big screens. The apparatus of security and remote tele-justice are unobtrusively built into the light timber panels. The actors of the court appear on cue – in person or on screen. A “back-of-house” circulation system of lifts and corridors separates four flows – those in custody, court officials, jury and judiciary. As in the lower court, the materials are neutral, the coat of arms discreet. It is a pity that the quiet hand of the Aboriginal artwork in the foyer and meeting rooms does not subtly colonize the courtrooms.

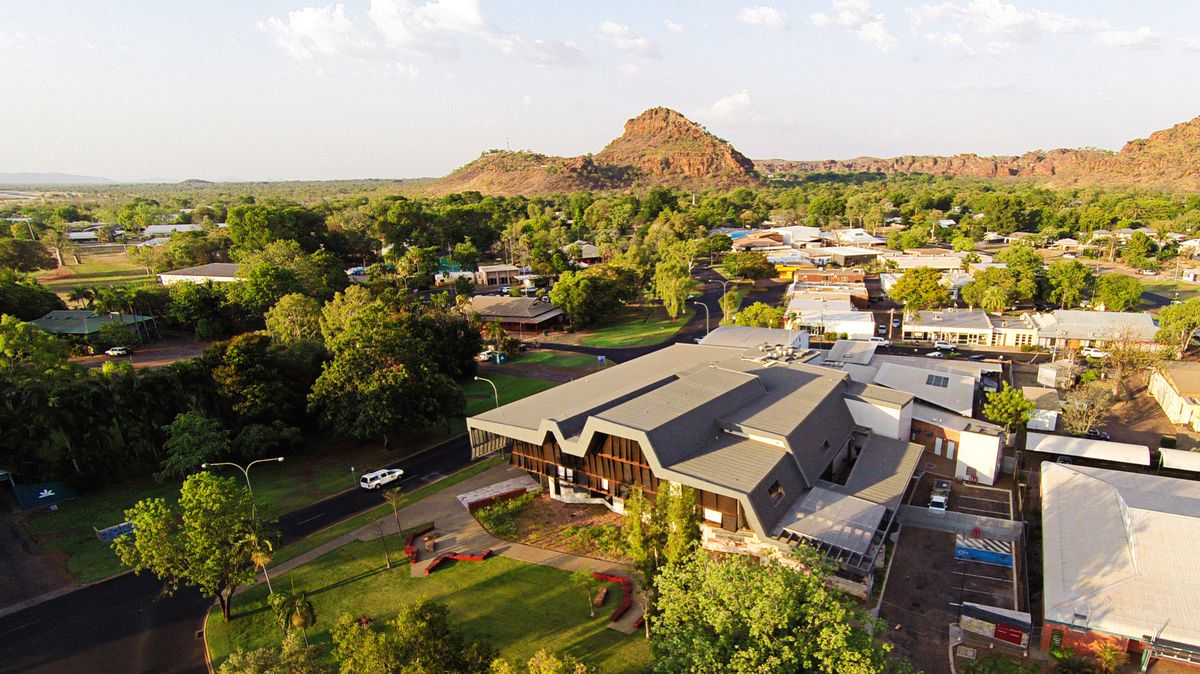

The folded roof is expressed inside the Jury Court.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Inside the building, the protective, folded roof seen on arrival becomes comprehensible, acknowledging the high courtroom sections. The folds above the Jury Court and its entrance produce a form that “sings” to the eroded forms of Kelly’s Knob and Hidden Valley.

The feeling of the approach and entry to the building is of “community” rather than “threat” or “civic pomposity.” The red, light ochre and grey, locally quarried stone leads us in. A volunteer on an unassuming perch assists anxious visitors. Ahead but hidden behind a screen are the counters where the business of the courts begins with some privacy. During the design process, Elders advised that backs were not to be seen from the entry.

To the right are stairs up to the Jury Court, interview rooms and a large waiting area for the selection of jurors. Views out ordered by louvres protect the privacy of those waiting. Two intertwined serpents at the foot of the stairs symbolize the joining of the laws of two cultures and this is evident wherever you look – from the brass handrails and fittings gathering a patina to the artwork.

On the ground floor, the feeling is less formal. A frieze of Indigenous artwork goes around the walls and past meeting rooms. The jarrah, Tasmanian ash and blackwood wall panels and seating zigzag the undulating peripheral walls in the waiting area – unlike the usual “serried rows” for waiting – like jagged rock formations. Like the work of Hans Scharoun, what is inside is outside: the seats push and pull at the stone base of the front elevation. Trees will enrich and soften this natural artifice.

A covered courtyard at the southern corner of the ground floor provides an external waiting area.

Image: Peter Bennetts

This jagged “escarpment” continues to the southern corner of the ground floor, where a partially covered courtyard is larger than the airconditioned waiting area inside. Many Aboriginal people who find airconditioning unbearable prefer to wait outside in the shade. The broad strip of shaded grass outside the entrance provides further waiting space. Offering both grass and seats, it is an enormously important and well located amenity. Happily – like the slots and gorge of Hidden Valley – there are many possible experiences for the inevitable waiting.

Kununurra is 16º S, Cairns 17º S and Darwin 12º S – all three well inside the tropics. Australia struggles with tropical building and towns, its building regulations and energy ratings generally devised for temperate climates. Moreover, the heat island effect, which can mean that towns are 10ºC warmer than their surrounding countryside, needs to be mitigated. This means coating tarmac with a white reflective coating, and increasing the tree canopy so that it covers more than 30 percent of an urban area – particularly shading tarmac. Though the sun is higher in the tropics, it hits nearly all the surfaces of a building – not just the north, east and west. The all-embracing and protecting parasol roof of the Kununurra Courthouse is an appropriate tropical move, but it would absorb and reradiate less heat if it was white. The parasol roof and screen shading on the northern elevation and the overhang and screen on the western elevation are responsive and deftly handled, and will be richer when the trees grow taller.

This building is remarkable because of its humanity, because of its framing of the lives of its people, and because it has been built with real craft in one of the most remote small towns in Australia. It is especially remarkable because its narrative engages with local Aboriginal culture.

Out into the intimidating heat of the day, and the Aboriginal family is still sitting in the shade waiting outside for the court to call – people inhabiting the shade and inhabiting their Land.

Credits

- Project

- New Kununurra Courthouse

- Architect

-

TAG Architects and Iredale Pedersen Hook Architects, architects in association

- Project Team

- TAG Architects project team: Jurg Hunziker, Michael Spight, Daniel Bubnich, Cynthia Teng, Julie-Anne McGuinness, Daniela Casadio, Hayley Brigatti, Melanie Burnett, Iredale Pedersen Hook Architects project team: Adrian Iredale, Finn Pedersen, Martyn Hook, Nikki Ross, Cherie Kaptein, Caroline Di Costa, Rebecca Angus, Jason Lenard, Mary McAree, Vincci Chow, Khairani Khalifah, Drew Penhale, Brett Mitchell, Jonathan Ware, Matt Fletcher, Mathew Omodei

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

Lloyd George Acoustics

Art Coordinator Malcolm McGregor

Code compliance consultant Milestone Certifiers

Electrical, lift & security engineer BEST Consultants

Hydraulic and fire services engineer BCA Consultants

Irrigation consultant CADsult

Landscape consultant Place Laboratory

Mechanical engineer DB Mechanical Consulting

Quantity surveyor Davis Langdon

Structural and civil engineer Terpkos Engineering

- Site Details

-

Location

Kununurra,

WA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Source

Project

Published online: 6 Jul 2015

Words:

Lawrence Nield,

Andrea Nield

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2015