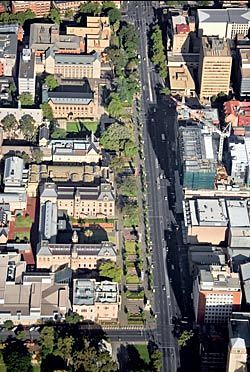

Aerial view showing North Terrace as a mediating element between the escarpment and CBD grid and the Torrens River below. Image: John Gollings

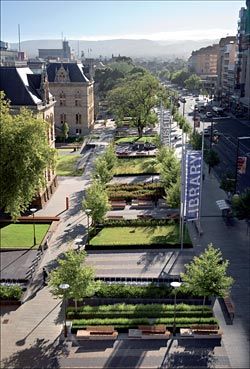

The city’s major cultural institutions line the north side of the Terrace. These buildings are now carefully framed by the Terrace’s new topography. Image: John Gollings

Looking along the length of the stage one redevelopment, which extends from the Library of South Australia to the University of Adelaide. Image: John Gollings

Looking west up the Terrace’s inner walk towards the library. Image: John Gollings

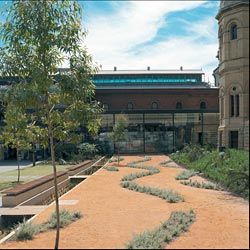

Sequential linear arrangements of pattern and texture carefully articulate the facades of the buildings along the escarpment. Image: John Gollings

Looking across the central mediating zone to the museum forecourt. Image: John Gollings

Looking east along the section of the Terrace in front of the art gallery. Image: Grant Hancock

Water is used in a variety of ways along the length of the Terrace. These features are also part of an extensive system for collecting and recycling water. A fine fountain plays in front of the library. Image: John Gollings

A linear pool with gentle waterfall bounds the space in front of the art gallery. Image: John Gollings

Water collects in Fourteen Pieces, an installation by Hossein and Angela Valamanesh in front of the Museum. Image: John Gollings

Playful planting draws on Victorian-era traditions of selecting plants to highlight architectural aspects. Image: Grant Hancock

The new wetland garden in the museum’s forecourt. Image: Grant Hancock

The careful detailing extends to the scale of street furniture and other elements. Image: Grant Hancock

Planting detail. Image: Ryan Sims

After long years of planning and politics and great persistence on the part of the urban design team – Taylor Cullity Lethlean in association with Peter Elliott Architects, writer and artist Paul Carter, and James Hayter and Associates – the first stage of the revitalization of Adelaide’s North Terrace is proving worth the wait. The city is typically imagined through Colonel Light’s iconic grid and the linearity of North Terrace, reinforced by its procession of major public buildings, has encouraged tourists and locals to picture Adelaide as a legible place. One that is easily traversable along a flat and wide streetscape, although that walk has long been affected by somewhat scruffy planting, ageing trees and a confusion of sculptures, statues, signs, street furniture and traffic.

This uneven journey is now interrupted by the first stage of the North Terrace Redevelopment, which spans the section from Kintore Avenue to Frome Road. This civic space on the north side of the terrace embraces the forecourts of many major institutions, including the State Library of South Australia, the South Australian Museum, the Art Gallery of South Australia, and the historical buildings of the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. A wall of commercial buildings fronts the south side of the terrace. This commercial side is not ignored by the new work, but North Terrace is aligned asymmetrically, both spatially and functionally, and the renewal of the street continues in this tradition.

North Terrace is often described as Adelaide’s cultural boulevard, and it carries high expectations for the functional and symbolic representation of the city. These expectations have been met with a design intervention that respectfully reinterprets the conditions that have framed the cultural development of Adelaide. The realized project is the product of a collaborative approach embracing history and tradition alongside contemporary concerns. Taylor Cullity Lethlean’s well-regarded design ethos – to creatively build upon tradition in seeking new imaginings of civic space – while constrained by the primacy of Light’s plan and a conservative city as client, has resulted in a layered spatial design and a precise programme of detailing that responds to local conditions. These new spatial and topographic elements now enable the Terrace to act simultaneously as both conduit and locale.

The initial framework document for the development of the entire North Terrace precinct provided a robust vision that has been successfully realized in stage one. It recognized that the Terrace has a many-layered identity – arterial road and civic spine, it is also the repository for the city’s collective memories and aspirations. In reflecting on the conceptual beginnings of the project, Kevin Taylor emphasizes the importance of Paul Carter’s work, which drew on Light’s original planning and the topographic origins of North Terrace. Light’s vision of North Terrace as a mediation between the escarpment and the Torrens River below, along with the linearity of forms between road and river, suggested a topographical approach to reimagining the Terrace.

Landscape and architecture can both be understood as topographical arts, produced through the interdependence of nature and art. The new urban design transforms the Terrace and its borders into a topographical composition, which is conceptually framed by the dual spatial meanings of terrace – both a flat surface, and a series of steppings mediated by the escarpment edge. In the new North Terrace such large-scale relationships between terrain and built form are topographically inscribed and architecturally reinforced through the articulated ground plane.

Upon entering the Terrace’s northern walks, the pedestrian is greeted by unfolding spaces which convey the variability and layered meaning of this civic space. The familiar double pathways of the former Prince Henry Gardens still exist but the mediating area, the thirteen-metre central flexible zone, encourages an altered negotiation. The southern border of the commercial city is still visible, but the immediate ground plane has emerged from the flattened plain in a kind of micro-topography that spatially refocuses one’s position between the chaos of the busy street and the formality of the institutional buildings.

Building upon a civic garden tradition, the planting beds, water features and seating step down towards the river. A new intensity of patterning and texture, in sequential linear arrangements running north to south, folds up to the architecture that marches along the escarpment. The eight-metre zone separating garden from road retains its character as a spatial buffer. Here, north-south movement is focused through the rhythm of insertions into paved zones, which interrupt the primary east-west linearity of the street.

The familiar four-metre walkway that hugs the buildings is expanded, not in scale but in presence.

It now invites the pedestrian to interact with the patterned surfaces, and establishes new spatial relationships with the built forms and garden fabric that border it. The library, museum and art gallery form a serrated built edge in a series of imposing, mostly Victorian-era facades, relieved by deep insertions and courtyards leading to contemporary architectural entrances set far back from the Terrace.

The walk along the inner Terrace now encourages a negotiation with garden and building spaces in very altered ways. The rhythm of spaces, where dense garden detail opens up to expansive paved areas at each building and its forecourt (redesigned to respond to entry conditions), emphasizes the spatial framing of the adjacent buildings.

Features emerge from the garden zone, encourage the pedestrian to pause, jump the walk and emerge again in forecourts, either in reality or through spatial association. Water, a precious resource in this arid place, is contained in a series of pools reminiscent of those seen in grander gardens. The library’s fountain plays a series of fine jets; the museum has subtle still water in Hossein and Angela Valamanesh’s Fourteen Pieces, which visually link to the stylized wetland forecourt garden; and the art gallery is bounded to the east by a linear pool culminating in a gentle waterfall. The poetics of water along the walk are also a subtle reminder of the pragmatics of good design: the water is part of an extensive system of gathering and recycling of local resources.

Pragmatic topography, the functional need for level change from street to buildings, is developed in a variety of devices: ramps, steps and platforms for future kiosks and artworks. The terracing of seating plinths infers a subtle mediation of the slope in association with the original landscape.

Material selection and detailing were informed by a desire for local presence. Paving was all sourced locally, from the sands to the judicious use of slate and granite. There is care in the small details, for example where Kanmantoo squares have been inserted into the precast to reinforce a building facade or to define a seating edge.

The attention to traces and marks inscribes a contemporary design sensibility onto the terrain of the Terrace. The design embraces the array of statues and existing urban detritus that speak the civic history of the place with a respect that often belies their material qualities. And the bold and playful garden plantings suggest an almost domestic gardening practice in their highly detailed planting compositions. Kate Cullity’s rationale for this intensity draws on Victorian-era garden traditions where plant selection favours the architecture through the use of striking and robust plants that reinforce each building’s spatial character.

Walking the new Terrace it is possible to pause in many places, to revisit the familiar, to review the detail of buildings and to consider aspirations for Adelaide from renewed perspectives. All routes offer themselves as sites to be experienced repeatedly, and variety and change are essential qualities of responsive urban space. North Terrace is an intensely detailed and complex space and it has gained wide public acceptance as a new urban garden for the city where designed topographies promote public exploration and delight. Yet the absences are also striking. The programme is incomplete. Elements that were planned but not realized, such as a contemporary architectural presence in the flexible zone and public artworks that invite imagining the city, have become invisible pauses in the Terrace.

To enable this civic space to become a place for gathering, and to respect the conservative values of this city while also suggesting that a contemporary imagination has relevance to other city sites – this expansive vision was the designers’ intent. Putting the “terrace” back into North Terrace has indeed been a challenge, and I look forward to the city taking up the project’s visible and imaginative legacy elsewhere.

Credits

- Project

- North Terrace

- Landscape architect

- TCL

Australia

- Project Team

- Kevin Taylor, Perry Lethlean, Kate Cullity, Simon Brown, Davian Schultz, Health Edwards, Susan Duldig, Carlo Missio, Peter Elliott

- Urban design

- TCL

Australia

- Consultants

-

Architect

Peter Elliott Architecture + Urban Design

Artist / historian Paul Carter

Civil engineer Dare Sutton Clarke

Graphic design Gregg Mitchell Design

Irrigation Hydroplan

Lighting and electrical engineers Barry Webb & Associates

Outdoor furniture design Dryden & Crute Design

Pavement engineer HDS Australia

Quantity surveyor Rider Hunt

Services engineer Dare Sutton Clarke

Surveyor DSC Andrew (now Andrew & Associates)

Traffic engineers QED

Urban design Peter Elliott Architecture + Urban Design

Water Feature Hossein and Angela Valamanesh, Fourteen Pieces., Sydney Fountains Waterforms

- Site Details

-

Location

Adelaide,

SA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

- Client

-

Client name

Adelaide City Council and the Government of South Australia