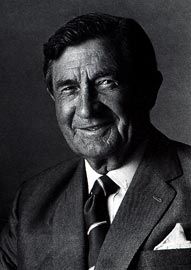

SIR JOHN OVERALL

Peter Ward remembers the achievements of Sir John Overall, the first commissioner of the National Capital architect from 1975 to 1983 and professor at UNSW.

When in 1958 John Overall arrived in Canberra to head the new National Capital Development Commission, the raggedy settlement was widely disparaged as “a good sheep paddock spoiled”. Fourteen years later, when he stepped down from his benevolent dictatorship, the future qualities of the city were settled. Canberra was steadily becoming the twentieth century’s most successful example of new national capital planning and development.

Overall was born in Sydney in 1913 and received his architectural education at Sydney Technical College where he won the New South Wales Board of Architects’ 1939 Overseas Travelling Scholarship. War prevented him from taking this and he joined the AIF, receiving his first commission in 1940. He saw early action in North Africa, where he was awarded a Military Cross and bar. After the war Overall worked first for the South Australian Housing Trust before joining the Commonwealth public service as Chief Architect in 1952.

In 1956 the Menzies government moved to end the 29-year absurdity of having cabinet and parliament meet in Canberra while the public service remained largely in Melbourne, and Overall recommended accordingly that the city should have a stand-alone authority responsible for all planning, construction and development.

His advice was accepted and in October 1957, 46 years after the Griffins’ plan had been adopted for Canberra, the NCDC was established. The following year he became its first commissioner. In 1958, apart from the recently completed Administrative office building, Canberra had hardly changed since the war. Its population of some 36,000 was in two small townships, separated by a flood plain and connected by a rickety timber bridge. The provisional Parliament House and the Australian War Memorial stood distantly either side of this divide, surreal sentinels guarding Griffin’s vestigial land axis.

Overall’s first challenge was to organise the NCDC as a building development authority able to provide the housing and office accommodation for the relocating public service, but it was a quandary where to start. As he put it later in 1982, following his receipt of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal, “How do you go about establishing a city? Notwithstanding Griffin’s plan, in 1958 there was virtually an empty canvas.” His solution was three-fold: a new town plan, budget and five year growth strategy; the completion of Griffin’s central lake system; and the construction of a new defence precinct at Russell, flanking the Australian-American War Memorial. The most important of these moves was the lake. When it filled in 1963 it instantly clarified the land-use pattern for central Canberra, establishing for all time the central city plan, as defined by the Parliamentary Triangle and the land and water axes.

Overall’s skills as an administrator and leader of creative teams were recognised in 1968 when he was knighted. When he stepped down in 1972 Canberra’s population was 150,000, its Y-plan of architecturally spirited decentralised centres had been established, and national institutions were being established or planned for the Triangle.

In 1972-73 he became founding commissioner of the Cities Commission, and later, among many public and private appointments, in 1979 he was pleased to be a member of the Parliament House Construction Authority. The completion of Parliament House on Capital Hill in 1988 was a cause of great satisfaction and he saw it as the pivotal move in the development of the city. “There now beckons a wonderful opportunity to finally establish Canberra as one of the great National Capitals and to complete the job as we usher in the twenty-first century,” he wrote in his memoirs.

His wife Margaret, described as his and his family’s “inspiration” died in 1988, and they are survived by four sons and many grandchildren.

Peter Ward

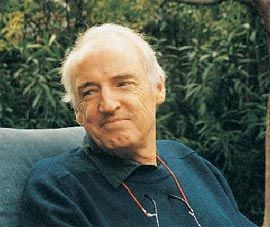

PAUL REID

September saw the deaths of two of the men who helped shape Canberra. Development Commission. Philip Cox farewells Paul Reid, the NCDC’s chief

Paul Reid had many loves – children, step children, music, theatre, literature, all the good things like swimming, skiing, the bush, but two loves stood out and transcended all others – his love for Wendy and for architecture. The two went hand in hand, for it was Wendy who stood by Paul through good and difficult times, encouraging him, exhorting him to better things – driving Paul to contribute as much as he did to his profession.

Born in New Zealand in 1933, Paul received his BArch from Auckland University in 1958 and a MArch from the University of Michigan in 1960. He was Chief Architect of the newly formed National Capital Development Commission from 1975 to 1983. After the demise of the NCDC, he was Assistant Director of Architecture at the Department of Housing and Construction (1983 to 1984). Paul was Professor of Architecture at UNSW from 1985 to 1998.

He was also a member of the Board of the National Capital Planning Authority. He published numerous articles on architecture and planning, with a heavy emphasis on Canberra and the National Capital.

I met Paul Reid when I was a young architect working on buildings in Canberra. I had been through the baptism of fire with Sir John Overall and Professor Gareth Roberts, Professor Richard Johnson and then Professor John Haskell working under the formidable chief commissioner. Paul Reid, as Director of Architecture, was kindly, sympathetic, understanding, and tolerant to me and to a whole range of architects, such as Col Madigan, Daryl Jackson, John Andrews, Ken Woolley, Harry Seidler, Peter Johnson, and many more who used to journey down or up to Canberra to present schemes to the commission.

I can recall one incident from Canberra days, with Commissioner Powell, Paul Reid as first Assistant Commission Architect, and Dick Clough representing landscape. One of my first commissions was Bruce Stadium.

As I presented the scheme, Tony Powell, in his usual way, described it as two eggs. Paul quickly quipped “poached or fried?” Dick Clough added “You know Philip, you had better come up with scrambled eggs, you will please nobody, so you better scramble them”. And so I did, helped all the way by Paul’s guidance.

During his time as Chief Architect at the NCDC, Paul’s most important role was the organisation and building of the New Parliament House. He was involved with all major works associated with Canberra and had a passion for that city which was refreshing, because Paul had to contend with many knockers like me, who did not always share his deep philosophical understanding of Griffin’s concept. His belief in Canberra was infectious so that, in the end, I was agreeing with him. The Griffin Plan was Paul’s creed. He took the time and trouble to understand it in every detail and he became its most ardent advocate.

Indeed, Paul believed the grand organic plan to be the most important new city of the 20th century.

His commitment to getting the story straight compelled him to research and write the book Canberra Following Griffin, a Design History of Australia’s National Capital. Sadly Paul did not see it finally printed, although he saw the proofs. The last five chapters are particularly intriguing.

Paul reveals the drama behind the staging of Australia’s grandest work and exposes some lost opportunities. Australia, he argued, had the opportunity to bring into reality a work of great genius, with a depth of inner meaning that surpassed both professionals and politicians.

Paul was loyal to his friends – so loyal that when he knew that his life would be short, he had the bravery to ring us all and tell us in an unemotional way that he had a problem and would like to see us. When you hear somebody tell you that over the phone, it is very hard after to shake a hand after a dinner and say goodbye, for the last time.

Paul will be remembered for his encouragement of others, especially the architects of the early years in Canberra, and the thousands of students he taught at UNSW. He is equally a loss to fellow academics and to the various committees on which he served. He will be missed for his happy and cheerful attitude to life both in good and adverse times.

Philip Cox