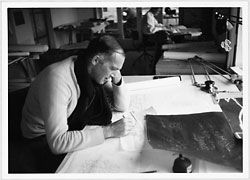

Jørn Utzon making a sketch for the auditorium ceiling design at Yuzo Mikami’s drawing board, 1960. Utzon studio, Hellebæk, North Zealand. Photograph by Yuzo Mikami.

Jørn Oberg Utzon, architect and furniture, lighting and boat designer, remembered by Philip Drew and Bill Wheatland.

“You have forced me to leave the job.”

So Utzon wrote to the NSW Minster for Public Works on Monday, 28 February 1966 about the Sydney Opera House. Earlier, he had been told by close colleagues not to send the letter but he did so against their advice. In addition to being prevented from progressing with his design by an obstructive client, he faced financial disaster as a consequence of his double tax liabilities in Australia and Denmark. The tax issue may not have been decisive, but it contributed considerably to his anxieties over the future of his Opera House design. Davis Hughes wasted no time and snapped up the resignation. Two months later, Utzon departed Australia, never to return.

The Davis Hughes confrontation is one of the great dramatic moments in twentieth-century architectural history. Utzon left the Sydney Opera House half finished, with only the initial stages 1 and 2 nearing completion and a spend of $18.4 million. Subsequent changes of program seriously compromised its architectural integrity – aesthetically, structurally and acoustically – so that it failed to fulfil the original specification for a major hall suitable for opera and symphonic performances supported by a second minor drama theatre hall.

The Sydney Opera House is Utzon’s most important work; his failure to complete it weighed heavily on him. He later appealed to Hughes to return, but the door had slammed shut. Utzon’s career was severely damaged by the tragic events in Sydney that affected him profoundly, professionally as well as personally. Much of the blame, especially over costs, was caused by politics: the hasty start to work before the building was documented, misleading estimates and lack of political accountability. The Cahill and Askin Governments were both culpable: the former in shifting blame to the architect, the latter for treating the Opera House as an election football. They added a further $80.4 million to the cost after Utzon left.

The Utzons derived from Kolding (on Jutland) in the sixteenth century, where they were merchants, quartermasters and dyers. Utzon is a variation of Udsen. His engineer father was a famed yacht designer of spidsgatter (double-ended craft), who managed the dockyard at Aalborg. Utzon attended school there before commencing his architecture studies at the Royal Academy in Copenhagen. At Alsgarde, he met the artist Carl Kylberg, who influenced his ideas on art and nature. Utzon arrived in Copenhagen as a provincial.

The occupation of Denmark in April 1942 caused him to flee to Stockholm soon after he completed his studies. He remained there until 1945, when he returned with Danforce troops reoccupying Denmark. The years immediately after the war were difficult; Utzon travelled to North Africa, USA and Yucatán to study Mayan architecture; in Paris he met Fernand Léger, Le Corbusier and Henri Laurens. Concurrently, he entered many architectural competitions and built a water tower and seamark on Bornholm Island, a simple house for his family surrounded by beech trees at Hellebæk (1952) and the famous Kingohusene courtyard houses (1960) outside Helsingør. In Sweden he was exposed to Gunnar Asplund and later collaborated with Norwegian Arne Korsmo, and worked briefly with Alvar Aalto on town planning at the studio.

Utzon’s success in the National Opera House competition in 1957 was a great surprise to him. He wanted to migrate to Australia immediately but delayed the move to Pittwater until 1963. The project made him a celebrity overnight. For the rest of his life he was never to escape from its long shadow. The building today is an approximation of what Utzon designed in 1956, which was greatly altered, first by Utzon and following his departure by Peter Hall, which has resulted in a confused and compromised masterpiece.

While working on the Opera House, Utzon found time to complete the Melli Bank in Iran (1959) and the wonderful Fredensborg housing group (1963) and a winning scheme in the prestigious competition for the Schauspielhaus at Zürich that advanced earlier themes from the Opera House, including an underground car park.

Utzon returned to a bleak reception in Denmark. His Zürich theatre project had been cancelled just when it was ready to go to tender and completion of his Bagsværd Church was delayed until 1976. Many of his Danish colleagues blamed him for Sydney.

In 1971, he moved to Majorca and built the “Can Lis” house (1972) on its south coast, inspired by the Majorcan vernacular and its clifftop location. It developed further ideas from his abandoned Bayview project (1964–65). In 1971, Utzon won the Kuwait National Assembly Building competition. His proposal was based on hanging roofs similar to Eero Saarinen’s Dulles Airport terminal. It resembled a giant white Bedouin tent pitched on the shore of the Persian Gulf. It too suffered from political delay and program changes that repeated much of what had happened in Sydney. He withdrew in 1978 and handed over its completion to his son Jan Utzon.

The Paustian furniture showroom on Copenhagen’s waterfront (1987) was Utzon’s final concluding statement on standardization and prefabrication. It marked his retirement from architectural practice. Although world famous, during these later years he had few opportunities to build. In 1994, Utzon completed a second Majorcan house, inland from the coast. It, once again, demonstrated his mastery of light and local vernacular technique.

In 1998, NSW Premier Bob Carr invited Utzon to return as a principal consultant for the refurbishment of the Opera House with architect Richard Johnson. This officially signalled recognition of Utzon’s central role as designer, and involved him through his son Jan in the future work. By 2003 little had been achieved, funds were still not allocated, though a simple document of design principles and development plans was presented in 2002. At eighty-five, with his health and eyesight deteriorating, age put a brake on Utzon’s direct involvement. Work on an integrated western lobby for the Opera House is projected to be completed by the end of 2009. In 2007, the Utzon Centre, in association with Aalborg University and designed by Kim Utzon, opened. It is linked to a study centre and houses the Utzon archive.

The Sydney Opera House design shocked doctrinaire modernists, who thought – incorrectly – that it denied functionalism. Among his generation, Utzon was the most adventurous. His approach, in contrast to the spare minimalism of Arne Jacobsen, was less an aberration than a return to a romantic fantasy encountered in H. C. Anderson, which overlays the plain ordinariness of Danish existence. Beginning with Asplund, Korsmo and Aalto, his underlying romantic sympathies are demonstrated by his adoption of Albert Frey’s “living architecture” ideas, attraction to anonymous vernacular architecture and eclectic pursuit of exotic influences, from north Africa, China and Iran to Yucatán and Japan. His aim seems to have been a synthesis of nature and vernacular principles to create a flexible, humanly satisfying, industrialized approach based on standard elements.

Nature was his ultimate paradigm. It is for the Opera House in Sydney that he will probably be best remembered, but his architecture is less focused on size or monumentality than on a sensuous celebration of the ordinary. His architecture is a shell for living, as close fitting and beautiful as a mollusc shell is to a mollusc. It was an architecture founded on modernism, inflected by a cool Nordic romanticism resonating with music, with the edges of life that sought out instances of anonymous timeless forms of growth and additive replication to convey his concept, “additive architecture”.

Jørn Utzon was a charismatic, handsome man who possessed enormous charm combined with a beguiling naturalness. He utterly lacked artifice. The unexpected death of his older brother, Leif, in 1964 was a family tragedy that caused him to worry about his own health. He was kind and generous and loved being around children, with whom he felt a great empathy. A loner, who was uncomfortable with fame, he chose to live an isolated existence close to nature. Stories abound about his kindness to strangers, his wicked humour and practical jokes. Nothing mattered more to him than his family.

Utzon received numerous architectural awards. Invariably it is the Sydney Opera House that is recognized: the major awards include gold medals from the RAIA (1973) and RIBA (1978), 1982 Alvar Aalto Medal, 1992 Wolf Prize, 1998 Sonning Prize and finally the 2003 Pritzker Prize.

Philip Drew is the author of The Masterpiece: Jørn Utzon, A Secret Life (Hardie Grant books, 1999); Sydney Opera House: Jørn Utzon, (Phaidon, London, 1995); and Utzon and the Sydney Opera House (Inspire Press, 2000).

When I graduated in 1963, many exciting places had awakened from the postwar doldrums and were experimenting with new materials and ideas. I packed my bags, travelled in Europe and ended up in Stockholm. The two years I spent working there were probably the most stimulating of my career – until Jørn Utzon won the Sydney Opera House competition.

In London I read of the NSW Government’s international competition to design an opera house at Bennelong Point. An Australian colleague and I applied for the details, but were not prepared for the magnitude of the project, which had to be literally accommodated on Bennelong Point. The house we shared was transformed into a mad house as we sought a solution. After weeks of frustration, partly because we believed the site was too small, we threw in the sponge and torched the partly finished drawings in the garden, much to the concern of the neighbours.

I was working in New York by the time I saw Utzon’s winning entry on the front page of the Sydney papers. I was incredulous. Had we been duped? Did Utzon kn0w something nobody else did?

Later, having returned to Melbourne, I contacted Utzon’s Sydney office and was told he was soon coming to live in Australia. I met him on site, we talked for a long time, and he asked if I would work as an assistant on the building’s design, with eight other architects and draughtspeople. I abandoned my Melbourne practice and settled at Bennelong Point, adjacent to the massive concrete structure now known as the podium. Once I became used to the Scandinavian way of running an office I preferred it – their design principles are never subjugated to expediency.

Utzon forged on with his detailed drawings of the roof tile lids and the huge plywood glass walls, trying to collaborate with the engineering firm appointed by the then Minister of Public Works, Norman Ryan, but our relationship with their Sydney office was never entirely cooperative and we were forever forced to seek advice from the London head office.

Then an unexpected change in the NSW Government threw us into total confusion. The incoming Liberal Party minister set about destroying Utzon, principally by not paying our architectural fees. I accompanied Utzon to the Minister’s office to plead with him to pay us so we could pay the staff; he refused, insisting on more drawings. Utzon said that without the money, we would have to close the office, sack the staff and leave the site. That’s exactly what he did, leaving for Denmark never to return.

For three years after Utzon left I worked with solicitors in an attempt to recover the monies owed by the NSW Government, but without success. The Minister’s actions in removing the designer of what is now the world’s most celebrated public building are unprecedented, and have sadly diminished the importance of the Opera House and heavily cost Australia’s credibility in terms of excellence in building design.

Bill Wheatland was a colleague and friend of Jørn Utzon.