PHOTOGRAPHY ROSS HONEYSETT

Review

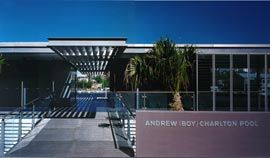

Entry to the new Andrew (Boy) Charlton Pool from the Botanic Gardens.

Changing rooms, with light filtered through the metallic brise-soleil that wraps the building.

Change cubicles.

View over the cafe and pool.

Looking along the 50-metre pool towards the north elevation, with the cafe deck overlooking the pool and the city and bay beyond.

View through the brise-soleil to the training/toddlers pool.

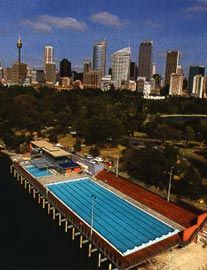

The pool complex seen from across Wolloomooloo Bay.

Aerial view. Photograph Robert Pearce, Sydney Morning Herald.

Entry from the Botanic Gardens, with the port in the distance.

Looking across the training/toddlers pool to the screened change rooms and staff areas, with the glassy form of the cafe above.

Canopies shading the toddlers/training pool.

View through the louvres, across the building, to the bay and city.

Looking north, across the training/toddlers pool, to the 50-metre pool with the docks across the bay.

FIRST LAP. This is a fact. The most exciting things happen on the edges of Sydney.

From the early settlers bathing along the western side of Woolloomooloo Bay to listening to a concert on the harbour, the pleasure of body underpins the lifestyle of this metropolitan city. Consider this: you might refresh your spirit by going to the Cathedral on a Sunday morning, or you could join the crowd at the Cook + Phillip Centre, located across from the Cathedral, and forget everything except the pleasure of sun, water and the body. Did not Le Corbusier miss Sydney in his journey to the East through which he became preoccupied with landscape, sun, and forms eroded by nature?

The redeveloped Andrew (Boy) Charlton (ABC) Pool pushes the complexities of Sydney’s public arena to a new level. The design, by Lippmann Associates, embellishes program and site just enough to recode the “culture of congestion” that Rem Koolhaas, in Delirious New York, attributed to the Downtown Athletic Club, built on the bank of the Hudson River, near the southern tip of Manhattan. The analogy is a good one: if the early twentieth-century architects of New York charged that city with congestion, and envisioned a metropolis that European architects could only dream of, Sydney flattens the Manhattan-esque density across its landscape. Sydney presents a plateau, a quilt, where various “plots” embody different activities, the total pieces of which describe the everydayness of a metropolitan lifestyle that is unique in this country. Where the Downtown Athletic stacked concrete floors on top of each other, the Lippmann Associates design suspends the pool above the shores of Woolloomooloo Bay, distributing two million litres of filtered harbour water into two outdoor pools and a deck with shallow water. Here, the experience of eating, swimming and human intercourse suggests a modest version of the social “Condensers” so dear to the Russian Constructivists.

SECOND LAP. Lippmann Associates’ design for the ABC Pool recalls the Miesian idea of “almost nothing” (a term which I find more satisfactory than the ubiquitous “minimalism”). This strategy discharges all possible narratives attributable to architecture except that of the site, which, in this particular case, means the amalgamation of landscape, memory and ruin. Every architectonic element – the direction of the suspended roof; the metallic brise-soleil that wraps the building and yet, like a swimming suit, also leaves some parts of the body of the building naked; and most importantly, the entrance bridge – is conceived and embellished to ensure the importance of the idea of architecture as landscape and nothing more.

This conjunction of architecture and landscape can also be understood within a dense recoding of the recent past. In the late 70s, postmodern architectural debate was hinged on the origin of architecture. Some were fascinated by typological investigations; others took the opportunity to simulate historical forms; still others considered archaic mythologies as the opening door to the beginning of architecture. (I am reminded of Claude Levi-Strauss’s structuralist discourse on primeval experiences. And of the New York Five architects’ recollection of the early modern formalism that was peppered with a sense of abstraction and “play” peculiar to the “primitive” work of art.) This rush for historical sentiment was modified by Vittorio Gregotti’s argument that making the landscape is the project of architecture. In response to the prevalence of image making, he wrote, “But in reality, the notion of landscape has been internally eroded by blind frantic occupation of space, and the neonaturalism that opposes this process is just as harmful to any human idea of landscape” (Inside Architecture, 1996, p. 14). Gregotti’s point is pertinent to Lippmann Associates’ attempt to mark the landscape without nostalgia, and without reducing architecture to a fetishised object, as much of today’s popular architecture does.

The ABC complex is seated on the top of the piers of many bygone structures. One recalls the much-remembered 1968 pool that suffered from a deteriorated concrete structure due to its proximity to the harbour, and the 1908 Domain Baths. Beneath all these layers, one inevitably recalls the Eora who once bathed around the site of the newly refurbished pool. Glazed at the harbour side, the design of the new pool not only opens its plateau to the vista beyond its immediate history, but also alludes to the presence of the Botanic Gardens and the city behind.

THIRD LAP. Approaching from the Botanic Gardens, one enters the ABC Pool via a bridge with a perforated deck. This deck both connects and distances the complex from the adjacent rocks. The sectional drawing speaks for itself: floating over the harbour, the entire volume is hooked to the cliff by the bridge. One could speculate on the metaphysical aspects of a bridge, but I would rather associate the architectonic of this entrance bridge with that of another Manhattan project – Marcel Breuer’s design for the Whitney Museum. The bridge at the Whitney was conceived to support the civic character of the museum. The ABC bridge instead recalls the decks of ferry landings on the harbour. This analogy is convincing not only because of the location of the entrance, but also because of the formal composition of the indoor spaces, including the cafe at the entrance level and the locker rooms and showers below. The overall form of the pool could also be associated with Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House in California, as my colleague James Weirick would like to say, if not with the image of liners – similar, perhaps, to the rusty ships standing on the opposite shore of Woolloomooloo Bay.

At the end of Delirious New York, Koolhaas writes the “Story of the Pool” to complete the “Postmortem” section. The story is a fiction, though it alludes to the history of contemporary architecture: the shifting of the historical avant-garde from its revolutionary context with the exodus of the Soviets of the early twentieth century to Manhattan. In this voyage, architecture lost its memory, and began to dwell on its own autonomy – either as a self-reflective form or as a landscape. Productive pragmatism is one harbour that the floating pool of contemporary architecture could land in. But, another is suggested in the design of the ABC Pool: the integration of program and site to produce an architecture that, like a stage set, stands back and leaves room for the event to take place. The architecture of this complex might not please those who have not learned their lessons from history and who would like to equate architecture with fashion-like seductiveness. Like the fictional architects in Koolhaas’s story, they might say, “the pool was so bland, so rectilinear, so unadventurous, so boring; there were no historical allusions; there was no decoration; there was no … sheer, no tension, no wit – only straight lines, right angles and drab colour of rust.” No worries! Standing on the deck of the ABC Pool, or swimming in its blue water, the building disappears from the sight/site, leaving the body to enjoy the tactile pleasure of material, the sun, the transparency of the horizon, and the depth of the dark blue oceanic water which one is constantly reminded of as the waves hit the rocks of the nearby shore.

Dr Gevork Hartoonian coordinates the masters program in architecture at the University of Sydney.

Project Credits

ANDREW (BOY) CHARLTON POOL

Architect Lippmann Associates—project team Ed Lippmann, Rolf Ockert, Nerida Bergin, Brian van der Plaat, Carmen Pereira, Melissa Doherty. Structural and Services Engineer Arup. Filtration Engineer Stevenson & Associates. Landscape Architects Peter Glass & Associates. Quantity Surveyor Rider Hunt Sydney.

Heritage Consultants Design 5—Katherine Forbes.

Archaeologist Godden Mackay—Matthew Kelly. Builder Reed Constructions Australia. Client City of Sydney— Marcia Aqui, Bill Tsakolos, Shane Henn.