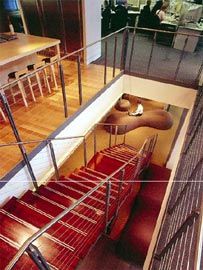

A new, open stair slices through the eleven existing floors. The stairs are disposed to avoid returns, thereby increasing the sense of space and volume.

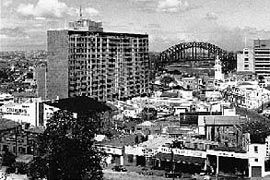

MLC, North Sydney in the late 1950s.

The refurbished exterior of Campus MLC.

The new entry to Campus MLC.

An early image showing the original entry at the first floor level.

The new glazed entry canopy emphasises the curtain wall above and the original entry opening.

MLC North Sydney interior, 1957.

New Campus MLC interior.

Interior views showing the range of finishings and furnishings used across the differently themed floors.Lift lobby with “graffiti” black board wall.

The Zen Den level has a table one has to climb onto to sit down and a tropical fishtank forms the wall to the elevator lobby.

Looking through the fishtank into the table room.

The Beach level with its striped carpet and industrial/warehouse type finishes.

Mid-century furniture used to refurnish a mid-century building, but in a very different manner.

Another interior view.

The “hospital curtain” meeting room. Images: Anthony Browell

When Prime Minister Robert Menzies opened MLC’s new highrise headquarters in Miller Street, North Sydney, in August 1957, nearly all the faces in the crowd were sombre suited men. MLC was then the largest office building in Australia. Inside were gleaming interiors and marching rows of desks, all sporting the latest look in corporate efficiency. Outside, Bates Smart & McCutcheon’s glazed curtain wall was a triumph of engineering. Today, the building looks just as fresh. The facade has been restored by Bates Smart’s Sydney office following a conservation management plan prepared by Peter McKenzie for Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis. The result is an exemplary piece of sustainability. To restore a 1950s skyscraper takes some courage. Not every corporation chooses to revive a potential dinosaur. Restoration is not necessarily a cheap solution or a sensible investment. To their credit MLC chose to stay and they did so throughout the refurbishment process. Inside, the changes wrought were dramatic. The new interior that is “Campus MLC” represents one of the most profound shifts in the history of postwar Australian office design.

The driving force in the process of creating Campus MLC was Rosemary Kirkby, MLC’s general manager of people. In 1985 Lend Lease had bought an ailing MLC and immediately set about turning its fortunes around. By the mid-1990s, MLC had moved from its pyramid-shaped hierarchy that oversaw the selling of life insurance to a “flat” structure of teams of people or business units who invented new products in the financial market. MLC, for example, was the first with internet on-line trading. The firm soon became hugely profitable and it’s no surprise that their new logo is “The Golden Egg”. Kirkby was acutely aware that the firm’s success was due to this new structure, which radically changed how people work, and also how they valued where they work. New spaces for Campus MLC were to be equally exciting, innovative, and different.

For the intensive consultative process that involved all MLC employees, Kirkby gathered together a team of design experts, including Debbie Berkhout, the Lend Lease Projects design manager, architects DEGW (Sydney), who provided programming data and coordinated the spatial integration of the various organisational units within MLC, and architect James Grose, of Bligh Voller Nield, who gave form to the resulting multitude of design ideas. Kirkby believed Grose’s expertise in residential design would bring an alternative way of thinking to the corporate interior. A one-week whirlwind tour of the “world’s best practice” in office design saw the team visit offices for Chiat Day in Los Angeles, Andersen Consulting in Chicago, Shell in The Hague, 3M in Paris, and, importantly, British Airways at Waterside near Heathrow (designed in 1989 by Norwegian architect Niels Torp and built 1995-97). This last complex sits on a 240 acre landscaped site and has as its major focus The Street, a 175 metre long glazed atrium that connects a series of low rise office slabs.

The message brought home was that for a totally new office landscape to succeed there needed to be a management commitment from top to bottom, and passionate engagement with the place and with people at all levels. There was also another factor to be considered. Kirkby explains it as follows: “Approximately seventy percent of MLC’s workforce are Generation X (i.e. those aged thirty-seven or less), who have entered the workforce during a period of unparalleled merger and acquisition activity. They understand the terms ‘downsizing’ and ‘right sizing’ and don’t expect, or seek, a ‘job for life’ as their grandfathers did in 1957…. They do not expect their careers to be linear; they may well change employer up to ten times, and may have several changes of career. For this generation, there is no stigma attached to being out of work for periods of time. Indeed work is increasingly seen as part of ‘lifestyle’.”%br% At Campus MLC, being at work might be preferable to going home! As Grose says, the task was to design “a place to meet” instead of “a place to work”. The commission was exactly the sort predicted by English office design guru and founder of DEGW, Francis Duffy. His books The Changing Workplace (1992) and The New Office (1997) speak of embracing new digital technologies and potentially rethinking the office analogically as hives, dens, cells, and clubs.

Under Grose’s direction, the first architectural response was to slice an open stair volume through eleven existing floors. This simple gesture was the most revolutionary – the creation of a vertical pedestrian street within a building type borne from the technology of the elevator. It was also an expensive slice, but one that would contribute to an “effective” not just “efficient” place/space. Each floor was then given a different name and themed accordingly, each having different furniture and different finishes.

Level 3, for example, is the Zen Den. At one end of the lift lobby, with its Richard Goodwin sculpture, is a series of three dishes filled with stones to relieve stress, and, nearby, there are giant amoebic seat-forms. At the other end is a tropical fish tank.

Behind the tank is a table that one has to climb up into to sit down – rather like eating at a Japanese restaurant. To use the white board you have to walk on the table. There is also no head of table. Another floor, with blue and yellow striped carpet and industrial/warehouse type finishes, is called The Beach. There is also The Table level, which has a kitchen and a massive table where one can eat, meet, or have a board meeting. If it all sounds gimmicky or embarrassingly twee it’s not. When I visited, people were in fact earnestly having meetings over cafe latte on Cafe Level 6. Others were using the shrouded “hospital curtain” meeting room, while a graffiti wall in one elevator lobby was clearly in use with Melbourne Cup sweep draws complementing business plans.

Grose freely admits that the life of the fitout probably coincides with a ten year cycle of office culture. This fashion for corporate renewal might have the same short life that open classrooms had in the 1970s. But the environment has a real sense of energy and activity. There is a sense too that the environment could change and adjust itself according to shifts in office culture. The original MLC floor plan, a central core flanked by two open floor plates forming an irregular H, is robust and ideally suited to such a radical rethinking of the generic office landscape.

There is also a practical side to all this. All computer services drop from the ceiling via simple galvanised steel service “posts”. There are fully adjustable work stations from Milan Unifor and no dedicated private offices throughout the entire eleven floors. Even the CEO, Peter Scott, doesn’t have an office. It is also an organisation that doesn’t require, for example, each employee to be surrounded by a library of books, or specialised equipment as required by doctors or radiologists. As an academic, I would be a certain pariah in such a place. There are hot-desks for interstate and visiting staff, numbers of four-person meeting rooms, and curved booths housing plotters and printers. All corners of the buildings are taken up not by offices but project rooms. No-one owns a window.

There are green pods for quiet moments and quiet rooms for private phone conferences.

The ends of each lift core all have small meeting rooms each with a different decor.

Outside, Bligh Voller Nield provided one element – a glass and steel-framed canopy that alludes to the steel-framing of the original building behind. The canopy’s glass roof makes one fully aware of the expanse of curtain wall above, and of the first floor level opening where originally a stair marked the entry to the building with a line of shops at ground level.

In such a complex collaborative weave of clients and architectural experts, the role of the solo architect has been jettisoned. There is no one author. Grose says this is not a traditional piece of architecture. That is true. While the architectural gestures are stylish, assured, and deliberate fun, what is innovative here is the entire package of program, architecture and the passion for change embraced by the organisation. Campus MLC has partial echoes in the 1989 decision to by ICI (now Orica) to retain ICI House in Melbourne (1955-58), and also the controversial battle in the late 1990s to refurbish Howlett and Bailey’s Council House (1961) in Perth. Where MLC is different, though, is the revolution that has happened within the organisation itself. As Grose observes, such a commission could only be achieved with a receptive client, an egalitarian approach achieved through a consultative process (a process that is not necessarily architect-led), and, importantly, a brief to create an environment rather than an interior.

For architects trained in strategic thinking, here is a perfect model for change.

Architects must understand the dramatic and profound shifts taking place in the workplace, and they must ensure that they too have the ability to change. It is not just the architect’s role which may change, but also perhaps the way architects work themselves, the way they work with others, and the way that client expectations may liberate architects’ own practices.

Dr Philip Goad is an associate-professor of architecture at the University of Melbourne. See also Alan Ogg’s detailed history of the MLC in Jennifer Taylor’s forthcoming book Tall Buildings in Australia 1945-1975 (Craftsman House, Sydney) and Peter McKenzie and Rosemary Kirkby’s essays on the recent MLC refurbishment in Sheridan Burke (ed.), Fibro House: Opera House – Conserving Mid-Twentieth Century Heritage (Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 2000).

Credits

- Project

- Campus MLC

- Architect

- Bligh Voller Nield

Australia

- Project Team

- Debbie Berkhout, Jenny Fusca, Mark Zaglas, James Grose, Bill Dowzer, Mike Hale, Walter Carniato, Russel Koskela, Nathalia Poliakik, Damien Mulvhill, Geana Gearty, Caroine Wilson, Tash Clark, Frank Ehrenberg, Adrian Light, Tinoulia Hill, Michelle Hosking, Ken Baird, Jim Milledge, Stefanie Flaubert, Jacqueline C Urford, Belinda Kerry, Vince Alafaci

- Architect

- Bates Smart

Australia

- Consultants

-

Rosemary Kirkby

Builder Lendlease

Facade engineer Ove Arup

Heritage consultant Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis

Original architect Bates Smart & McCutcheon

Project delivery Bovis Lend Lease—Reece Marjoram

Project manager Bovis Lend Lease—Debbie Berkhout, Mark Reynolds

Workplace advisor DEGW

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

- Client

-

Client name

MLC